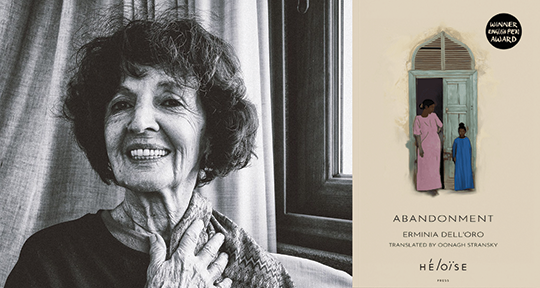

Abandonment by Erminia Dell’Oro, translated from the Italian by Oonagh Stransky, Héloïse Press, 2024

Why do we leave behind people and places? Is it painful or bittersweet? Does it indicate bravery or cowardice, altruism or egoism? Do we have complete agency in these decisions or are we instead constrained by necessity, oftentimes masked by the illusion of choice? What kind of person do we become in the aftermath?

In Erminia Dell’Oro’s Abandonment, a rainbow appears in the sky like a sign from God. In its wake, the novel’s protagonist, Sellass, decides to leave her village of Adi Ugri (now Mendefera in Eritrea) in search of a better life. “To feel less lonely on her journey, she daydreamed and sang. God had created a bridge that would carry her far from her village, she was crossing the sky, and the spirits of the air travelled silently by her side to keep away fear.” Meanwhile, in an Italian town close to Pavia, Carlo is leaving his family to try and find fortune in America. Although he returns soon after, “his old hopes” in the New World struck down by poverty and the threat of war, he later sets sail for Eritrea with a feeling of elation. It was “as if, for the first time, life itself—with its variety of colours and sounds and in the warm soothing sensation of the sun on his skin—was mysteriously promising him happiness.” The two will soon meet and go on to have two children together, creating the familial line that weaves through the novel.

Dell’Oro portrays these hopeful beginnings through linguistic prisms of light and color, brightly reflecting off of the novel’s bittersweet opening scene: a folktale explaining the origins of the rainbow. In this magical iteration, the universe created the stars, but then realized it was alone and would be for eternity. “A host of angels flew across the skies, the light dappling their wings with colour, and disappeared.” When the universe began to cry, the tears crystallized “into alternate worlds that preserved the dream, or memory, of those luminous wings,” forming arches of brilliant hues in the sky. Thus, whenever a rainbow appears, it is a sign that “the cosmos recalls its ancient suffering and the trail of colours that gently caressed it to lessen the pain.”

The tale is a chimeric entryway to the remainder of the novel, in which Dell’Oro intertwines reality, memory, and dreams to examine the bittersweet nature of life and death, loss, and resilience. She challenges the reader to consider the myriad nature of abandonment and how we process painful experiences, often through phantasmagorical dream sequences; Oonagh Stransky’s translation is particularly masterful in such sections, capturing the fluidity and lyrical quality of the original. These dreams highlight the inaccuracies and biases inherent within memory recall, obfuscating the line between reality and imagination, and seamlessly blending them. More than a mere stylistic device, they prove integral in experiencing the characters’ subconscious struggles with abandonment and loss, while enhancing the emotional depth of the narrative.

In Sellass’s first dream, ocean waves engulf Massawa and the island of Sheik Said. Her form merges with the water, which adorns her with seashells, coral flowers, and pearls. Then, as a sea urchin pierces her heart, she attempts to cry out, only to find that her voice has deserted her. Upon waking, a handicapped soothsayer named Mariam foretells her future and reveals that an Italian man will soon enter her life. The rest, however, remains hidden from her, and foreshadows the struggle she will soon endure.

This vivid sequence proves to be the most imaginative of her dreams. As the story unfolds, Carlo abandons the family, leaving Sellass to face relentless hardships, and her dreams gradually fade into a blend of memory and lingering sensations; “the briny scent of low tide by the salt flats” only evoke happier times with Carlo and their children, Marianna and Gianfranco. Eventually, at the end of the novel, a flood of memories overwhelms her during a hypnagogic state, when “images from days gone by, imprisoned by time within those four walls, returned to her in the dark, as if on a stage, bringing a variety of scenes and sounds from the past to life.” By then, she has forsaken the daydreams and songs that once defined her youthful, carefree spirit. Her dreams, once vibrant and filled with imaginative stories, have become a painful reliving of memories trapped in time.

As Sellass’s dreams fade into looping recollections, her daughter Marianna’s begin to flourish, offering her a brief escape from the harsh reality of being a “mixed-race” child of a single mother in Italian Eritrea. “When she was sad, she liked thinking about sleep, about the magical way it quickly erased all the day’s troubles and created an enchanted otherworld where all sorts of things could happen.” Marianna finds solace and clarity in her dream world, and, unlike the dimming visions of her mother, Marianna’s imagination is vibrant and full of life, bursting with the boundless hope and endless possibilities that only a child can conjure.

These dreamscapes become a vital part of her inner strength, a place where she can nurture seeds of hope and resilience. Throughout her life, Marianna often blends memories with imagination; on a cold night in their new home at Edaga Arbi, she dreams of revisiting the flamingos that she saw years prior—the lake and sky are bathed in a golden hue, and her father is standing nearby, gazing at the water. As everything else fades away, Marianna clings to one of the flamingos by its neck, first soaring through the air, then plummeting, only to be caught by a blue kite that her father had flown in earlier days.

As the novel unfolds, Marianna’s dreams evolve into an amalgamation of memory, fantasy, and clairvoyance. She develops a preternatural ability to perceive hidden truths and foresee the future, blurring the lines between reality and the dream world even further: her nightmare at the boarding school blends into a friend’s death; she envisions their family’s future home in Amba Galliano. Marianna’s journey—first alongside her mother and later as an independent woman in Italy—is especially compelling, marked by profound losses and surprising moments of renewal. Her prophetic dreams, and their eventual fulfilment, highlight the novel’s exploration of destiny and personal agency.

Unlike Marianna, her brother Gianfranco retreats into himself, as if in a waking dream. “It was as if he lived in a different world, one filled with silences that she did not understand.” This inwardness is mirrored in the rarity with which Dell’Oro writes from his perspective. In one particular chapter, he leaves school and, “for the first time in a long time, Gianfranco felt happy. He looked at the cloudless blue sky, the palm trees on the main avenue, people walking by, and the tall clocktower, and everything seemed new to him, as if he had woken up from a long sleep and was seeing the small bright city for the first time.” He takes up work as a carpenter’s apprentice and, in his only dream sequence, envisions an abandoned Edaga Arbi, haunted by the souls of its deceased inhabitants, now embodied in coils of wood.

Gianfranco’s silences become “a form of escape, like the constant games he played of building and then destroying things.” This cycle of creation and destruction echoes the novel’s broader themes of abandonment and replacement, life and death, giving and receiving. Dell’Oro often portrays abandonment as an act fraught with implications of betrayal and renewal, a symbol of hope and continuity amid loss: fortune in the New World with Sellass’ love, or Mariam’s death with the birth of Marianna, for example.

In its portrayal of Eritrea’s sociopolitical landscape, Abandonment is detailed and nuanced. Having been born in Italian Eritrea in 1938, Dell’Oro does not shy away from depicting the harsh realities of life in a country marked by war and upheaval, and she employs her unique perspective to explore belonging and identity through the lens of personal memory, set against a collective narrative. Her characters are profoundly human, each wrestling with their own fears, hopes, and desires, but their intertwined paths reflect the broader historical and political upheavals, offering a deep and empathetic portrayal of colonialism’s enduring impacts and the continual quest for identity in a fractured world.

Dell’Oro’s works have received both positive and negative commentary over the years, with some accusing her of imbuing colonialism with nostalgia and others praising her ability to raise public awareness—especially among Italians—of the nation’s colonial past. The first criticism is perhaps unwarranted, for the racial divisions depicted in Abandonment do not portray the colony as a utopian space for which one should pine, but rather a harsh environment in which only the strongest survive. It is a place of privileged Italian colonists and native-born Eritreans, full of tension and strife. In Abandonment, movement and displacement are not idealized; Dell’Oro addresses the often cruel reality in Italian Eritrea through the traumatic experiences of a woman and her two children, “abandoned” by their Italian father, thereby dismantling the common myth that Italy’s occupation of Eritrea was a more benign colonialism compared to that of France or England.

Abandonment was first published in 1991, and Stransky’s translation breathes new life into this work, ensuring that its emotional depth and cultural specificity will continue to resonate with contemporary readers. She captures the essence of Dell’Oro’s prose, preserving the cultural and emotional nuances, as well as the singularity of the author’s style. Her lexical choices also reflect a deliberate effort to maintain the source’s tone and context; the term “mendicant,” for example, is used to describe an old woman who praises Sellass for not abandoning Marianna in the convent, whereas the term “beggar” is reserved for the more malicious vagrants in the story, disassociating the two groups. Stransky also maintains the gendered language inherent in the characters’ cultural milieu, in which the sun is referred to as male and death as female, casting them with a human quality and bringing them closer to the characters. In contrast, a Christmas tree is described as “it,” emphasizing its disconnection from life, and elaborating the metaphor for a broader theme of loss and severance.

Through Stransky’s expert translation, the English edition of Dell’Oro’s Abandonment introduces a compelling and thought-provoking novel that delves into the complexities of abandonment and resilience, challenging readers to reflect on their own experiences of loss and renewal, and offering a deeply moving exploration of the human spirit. This rediscovered gem stands as a testament to the power of storytelling and the vital role of translation in bringing such stories to a global audience, bridging cultural and temporal divides and resonating with readers across the perpetual, universal cycle of people searching and finding, leaving and staying.

Rose Facchini is a Lecturer in Italian at Tufts University and the Editor and Italian Translator Editor for the International Poetry Review. Her translations have either appeared or are forthcoming in 365tomorrows, Asymptote’s Translation Tuesdays, ergot., Exacting Clam, Fictive Dream, Heimat Review, International Poetry Review, Intrinsick, West Branch, and Wyldblood. https://linktr.ee/rose_facchini

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: