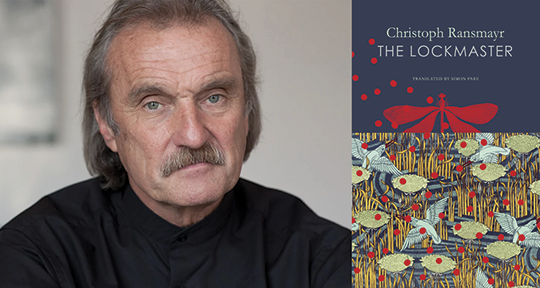

The Lockmaster by Christoph Ransmayr, translated from the German by Simon Pare, Seagull Books, 2024

The Lockmaster, the latest novel from Austrian writer Christoph Ransmayr, begins with an act of killing in a small European town. The narrator’s father—the titular lockmaster—presides over a series of sluice systems for guiding river traffic around the Great Falls, a cascade over a hundred and twenty feet high on the White River. On a festive day, ironically a day to celebrate the feast of Saint Nepomuk, the patron saint of those in danger of drowning, the lockmaster floods a navigation channel carrying riverboats. Accidental or otherwise, this episode claims five lives. A year later, almost as if in atonement, the lockmaster stages his disappearance into the same foaming roars of the Great Falls.

Tortured by the possibility that his father could be a murderer, the narrator goes on to experience a series of harrowing events as his hydraulic engineering projects carry him from the banks of the Xingu River in South America to the Mekong in Asia. By the time the narrator travels back to Europe and to the coasts of the North Sea, he himself has transformed into a murderer. Throughout, Ransmayr details the narrator’s childhood with gentle premonitions of his transformation, with prose that feels like a moving panorama of the idyllic outdoors, soaked in an aesthetic genre that seems almost “cottagecore”; yet, existing collaterally with the seemingly quaint charm of strawberry-picking and kayak rides, amidst riparian forests and river spirits, there are far more disturbing scenarios.

Crafted in German and translated by Simon Pare, The Lockmaster traverses continents and journeys through time, situated in an imminent future of global water wars. Even as a child growing up near the White River, the narrator had witnessed the dismemberment of larger European states into innumerable micro-states, demonstrated in the dwindling number of ferry connections and bridges along the watercourse. When such fractures find their way into his own family, as ethnic laws require his mother to return to her homeland, the tale also becomes the family’s personal archive. After his mother disappears in a convoy of deportation buses, leaving behind her two children and presumably a loveless marriage, the narrator’s resentment towards his father only grows. The patriarch is described as a man who has always evoked more fear than love, a man capable of terrifying bawling at the slightest of pretexts and, at the same time, of singing many-versed river songs; long before the narrator suspects him of being a murderer, he is seen as the devil. Like the shape-shifting denizens of the riverbed in bedtime legends, he imagines his father taking the form of a waterlily before mutating into a dragonfly, a kingfisher, or a bloodthirsty troll. In the English edition published by Seagull Books, Sunandini Banerjee’s jacket design visualizes this phantasmic emotional canvas of the narrator with impressive vividity.

Shaken with first-hand testimonies of genocide survivors as he navigates the Cambodian countryside as an adult, the familiar canvas of his childhood reappears in the narrator’s mind. Comparing his father’s sadism to that of dictators who feel entitled to command the fate of living beings and natural environments, the narrator becomes convinced that the spectacle of horror at the Great Falls, beheld by helpless, screaming tourists, was premeditated. He concludes that perhaps his father had desperately longed to return to the past through this murderous act, to a time when networks of watercourses were more inherent to navigation and hence the relevance of lockmasters more undisputable; in the absence of such routes, he was no more than a curator of boat passages. The narrator recalls:

Shortly before the latest ethnic laws forced my mother Jana to leave him and return to her native Adriatic shores, she embroidered the chest pocket of one of his shirts, where he always kept the river-flow chart handy, with his title in silver thread: Lockmaster. . . . To me and my sister, Mira, who had overheard local people make sarcastic jibes and giggle about the curator’s self-appointed title, it seemed at the time as if, before her departing, our mother had embroidered a mocking nickname on his chest, and he took it with him to his doom.”

The lockmaster’s hatred for contemporary life further reveals itself in the narrator recollections: “Our father kept not just our mother Jana more or less captive in the ravine by the Great Falls. . . but us two children, as well, and very rarely were we allowed up into the present day beyond the edges of the gorge.” Obsessed with preserving an archaic world, the lockmaster moulded his family to be the first victims of his tyranny.

However, it does not take long for the reader to realize that the narrator too remains preoccupied with the past. The soundscape of his childhood often echoes tirelessly inside his ears, in the all-consuming roars of the Great Falls. He confesses: “. . . even during my years working on dams across Africa, South America, and Asia, I often yearned for the bewitching, deep-green beauty of those legend-laden, myth-charged playgrounds along the sandbanks and gravel shoals of the White River’s gorges.” But because the past he pines for appears hallucinatory, existing only in his extreme fantasies, the narrator ultimately comes across as unreliable. An isolated boyhood—marked by the sudden absence of the mother, a father imagined as the devil, and the mythical incarnation of a sibling with brittle bone syndrome into a glass fairy—is suffused with the twin sentiments of fear and incestuous desire. It is also a boyhood where moments of suffocating rage, possibly inherited, finds expression in grotesque acts: moments in which the narrator would shapeshift into the devil and his father would be a mute bystander. Such acts foreshadow how, years later, the narrator would try to impose his mental fictions on reality.

This desire to inhabit the past, shared by both the lockmaster and his son, is further complicated by the fact that the human experience of time—in whichever manner one seems to experience its course, through myriad moods and emotional states—is ultimately a tiny speck in the unimaginably vast duration of geological history; we are living at a time when the trajectory of one’s life is irrevocably linked to the Anthropocene Epoch and its realities. Inevitably then, encasing an account of a family’s life and crimes, Ransmayr’s latest is a chronicle of an imminent future where emotional disorientations encounter environmental turmoil.

Ransmayr’s style is intricate. He makes readers confront the post-apocalyptic—effortlessly bringing together human and non-human time. The fact that the narrator’s life unfurls in the company of watercourses is, itself, an ode to such coupling. A boyish soundtrack of the White River’s whirlpools and eddies and the roars of the Great Falls meets an adulthood spent working on the banks of numerous rivers in myriad continents. The moods of the Tonle Sap afflict the narrator, reminding him of his father’s nightmarish temporal detour; even his romantic fantasies take him to the banks of the ancient Nile. On the coasts of the North Sea, he shape-shifts into a murderer. Finally, it is in a ghost town near the Adriatic Sea that the Mediterranean myths and fairytales of the narrator’s childhood coalesce with the contemporaneous destruction of local habitats; there, the fictions of his own life—the ones of his invention—also simultaneously wane.

There are shocks in store for the readers of The Lockmaster as the narrator sets off in search of his family members—who, unlike him, have discovered ways of escaping their temporal entrapments. But what lingers long after the reading is the gloominess of the novel’s forecasts: a fractured future of ravaged ecosystems and technological excess awaits, strewn with withdrawn, hyper-surveilled communities, where immigration is impermissible and incest is prescribed. It is a world where newborn microstates—named after hydro-alliances—inaugurate newer borders and engage in tireless, violent conflicts. Amber deposits, from a time incomprehensible to human experience, wash up on the shores of the North Sea from the Baltic. All the while, oceanic current systems collapse, glaciers melt, and sea levels rise, eventually consuming even the narrator.

Moumita Ghosh is a Kolkata-based freelance writer and researcher.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: