We all love our books, but at what point does that love become reductive—or even dangerous? Italian writer Michele Mari weaves elements of materialist obsession into his fictions, describing how one’s attachment to literature can create falsifications, egomaniacal delusions, and objectifications of the people around us. In this following essay, Francesca Mancino takes a close look at Mari’s You, Bleeding Childhood and the recently published Verdigris, tracing their narratives in their manifestations of literary greed.

In the threaded lines that clutter all but the gutters of his works, Michele Mari comes close to Becca Rothfeld’s fantasy of excess, as detailed in her essay, “More Is More.” There, she writes, “I dream of a house stuffed floor to ceiling; rooms so overfull they prevent entry; too many books for the shelves; fictions brimming with facts but, more importantly, flush with form; long tomes in too many volumes; sentences that swerve on for pages; clauses like jewels strung onto necklaces. . .” In both the collection You, Bleeding Childhood (2023) and the novel Verdigris (2024), translated into English by Brian Robert Moore, there is a feeling that the text cannot contain the objects described. It is as if the words command a vaster space than a page can allow for.

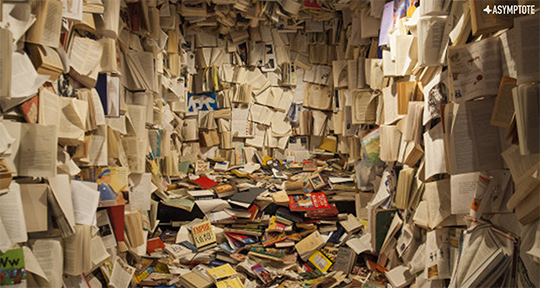

Mari’s work toes the line between the wonder and the obscenity of excess; in both You, Bleeding Childhood and Verdigris, the author presses his readers to think about its many forms and their respective limits. Reflected in his writing style, one could almost say that there is too much in Mari’s books—too many literary objects, household items, convoluted adjectives, coveted authors, and blended dialects. In Verdigris, the walls of a home have almost no free space because “everywhere has gradually been overrun by objects and signs drawn on paper, when not by symbols traced directly onto the plaster. Anyone walking into that room would have the impression of a random and compulsive clutter, as though owing to a kind of horror vacui.” The narrator, Michelino, reminds the reader that the objects are not arbitrary, since he and Felice, the house’s owner, share an intimate knowledge of “every single element” tacked onto its surfaces.

You, Bleeding Childhood and Verdigris differentially explore the zany habits of collectors who allow objects—and the memories they evoke—to govern them. Much like Walter Benjamin in his essay, “Unpacking My Library,” the collectors in You, Bleeding Childhood and Verdigris have a special thirst for objects concerning literature and relating to linguistics. For them, collecting signifies a dependency on nostalgia and memory, all of which coexist with each individual object. They actualize Benjamin’s statement that “every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories.”

In You, Bleeding Childhood, a young boy Michelino has a special affinity for literary items; the toys, monsters, books, and writers of his childhood are catalogued in stories that continue the throughline of how these same objects loom large in his adult life. In Verdigris, a groundskeeper named Felice transforms his home into a museum-like trove of objects, which Michelino preserves in his quest to restore Felice’s memory. (Abundance also rests in the fact of characters named Michelino in both texts.) Because literary objects—and authors in particular—direct both of these narratives, it is worthwhile to untangle their origins in Mari’s work. Literary excess, in his oeuvre, has many manifestations: points of view adulterated by writing and reading, the toppling of personal canons, and collections with grotesque pictorial details.

*

Both Michelinos share a predilection for nineteenth-century literature, and this love is twisted into something more sinister through their obsessive natures: does fiction simply invigorate their worlds, or does it deceptively alter their realities? In Verdigris, the case for the latter is stronger; a teenage Michelino views Felice, an elder gardener employed by his grandparents, through a lens that is distorted by literary influence. Michelino incarnates objects with double meanings for Felice, who relies on these new associations as his memory fails more as each day passes. A postcard with an aurora borealis illustration, for example, serves as a trigger for the name of Felice’s presumed father, Aurelio. Together, Michelino and Felice create a memory museum out of the latter’s home, where objects are on display to be subjected to linguistic scrutiny. Every item—ranging from a milk carton, a toy car, and a sausage—is connected to an idea, person, place, or thing that Felice has forgotten. Yet Michelino is not simply being charitable in creating this index of references; with a personal canon that includes Melville, Lovecraft, Adorno, Lukács, Tolstoy, and Dickens, his thirst for fantasy self-servingly colors his motivations.

Verdigris’ Michelino later lets it slip that he is projecting meaning onto his encounters with Felice, hoping to create a reality that reflects the content of his books. (Moore touches on this in his afternote: “Michelino, in fact, knowingly projects the books he has absorbed onto his companion.”) When Felice handles the eponymous verdigris, a teal substance used to coat grapes, Mari points to how both Michelino’s perception and the narrative are corrupted by nineteenth-century texts; the act is described as being done with an “intimacy,” much like how the Pequod’s men squeeze the spermaceti in Moby Dick. In another scene, Michelino projects even more forcefully when he hands Felice a pen once owned by the former owners of his grandparents’ home. He hopes that a recollection will accompany Felice’s handling of it, but Felice begins speaking in French instead, to which Michelino asks pointed questions, one of them being: “Who’s writing?” Felice strangely says that Michelino is, inside of him. Michelino then admits:

I had built myself a little nineteenth-century novel full of anagnorises and dramatic twists, and I wanted Felice to embody and to give voice that novel, deriving it from the energy unleashed by that pen, which instead released nothing but a puff of purple dust. If this was the case, then I was the most disruptive and confusing element of all—I who therefore needed to find a way not to interfere so violently.

One question underlying the narrative is whether Michelino’s efforts to bring back Felice’s memory are more selfish than noble or vice-versa. Undeniably an unreliable narrator in the way of Poe, Michelino foists his “Pushkinesque novel” onto Felice, denying him of his autonomy while allowing his own creative liberty to run rampant. Michelino’s literary appetite is only whetted when dramatizing Felice’s backstory—all while inserting himself and his books into that narrative.

Aside from the lexicon-based collection that has invaded Felice’s home, collecting also takes on an abstract form in Verdigris. Indeed, Felice eventually morphs into a composite of Michelino’s coveted fictions, becoming the ultimate example of embodied excess; he is obscenely grotesque (with his “smallpox ulcers” and “chronic pinkeye”) and wonderfully complex, though he has “nothing of Captain Ahab about him.”

As Michelino will later learn, potting his fictions with the soil of his surroundings only leads to disillusion. “And even adventure, which I could conceptualize only in the ways established by Stevenson, by Melville, and by the other greats who had taken me by the hand, even adventure had perhaps ended with them.” After learning more about Felice’s identity, he is left with only a “shabby caricature” of adventure culled from children’s television shows; Michelino’s layered visions of reality are eventually trimmed of their fat.

*

You, Bleeding Childhood’s Michelino is a “morbid, fetishistic keeper of everything,” who archives his belongings with an “obsessive affection.” In the first of eleven stories in the collection, “Comic Strips,” the titular texts are sublimated to biblical proportions. “They are religion” and “object[s] of worship,” deservedly sitting on the highest shelves of Michelino’s home library—in contrast to the texts that others would deem more worthy, such as “the products of sixteenth-century printing presses and baroque folios.” The comic books tower above volumes of Antonio Zatta and Giambattista Bodoni, Silvestri and Sonzogno imprints, series by Medusa and Struzzi, and Pléiade and Ricciardi collections. Whereas Benjamin holds that a book’s entire history—its acquisition, year and region of publication, and former owner(s)—endows it with a mystical aura, the books that Michelino owns possess only personal intimacies: “They are imbued with my own sequels and re-elaborations, entities such as these, they compartmentalize unrepeatable days, such vignettes (beloved squares, adored rectangles, emblems of my room, insignias of my bed), yes, yes, they are history.” In this iteration of bibliophilia, each book’s history is inextricably laced with one’s own.

Notably, books from the Urania series, a science fiction publication, are on the same shelves as the comic books. In “The Covers of Urania,” Michelino recalls a memorable dream wherein Robert Louis Stevenson asks to borrow his Urania paperbacks, at which point the narrative structure begins switching back and forth between succinct bibliographic descriptions and Michelino’s exalted syntheses of the Urania books. His enchantment with them is embedded in the story’s style, which is saturated with superfluous descriptions that mirror the “obscene excess” of supernatural content in Michelino’s mind. Before individual covers and titles are analyzed, Mari goes into forty-four sequential adjectives to describe a laundry list of monster types, which include “flaming,” “frenzied,” “metaphysical,” and “ulcerated” sorts. The bibliographic bits of information contribute a sense of order to the story, somewhat echoing Benjamin’s claim that “if there is a counterpart to the confusion of a library, it is the order of its catalogue.”

While an abundance of literary objects take center stage in the aforementioned stories, “Eight Writers” follows a process of condensation and, eventually, elimination—as evinced in the story’s first line: “There once were eight writers who were the same writer.” Contrary to Rothfeldian shelves of overflowing tomes, the narrator seeks to abridge the corpora of Joseph Conrad, Daniel Defoe, Jack London, Herman Melville, Edgar Allan Poe, Emilio Salgari, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Jules Verne into a single volume. The overlap of seafaring and adventure as shared themes bind these writers together for Michelino, and he struggles to untether them stylistically. In trying to prove their similarity, he points out a line that could be attributed to any of them: “The dawn’s gloomy light allowed him to verify how warranted his fear had been: in the small barrel, not a drop of water was left.” His solution to maintaining uniformity is to conjoin their fictions together, as if “all of them had written that line.” Therefore, “their characters, too, were the characters of a single great book,” and the speaker is a “protean narrator.”

Lumping these writers together, along with their works and characters, proves to be a self-inflicted wound. In Michelino’s attempt to converge his childhood favorites, elimination is necessary. “Having fallen for superficial similarities,” he pins the writers against one another to crown a king of his personal canon. However, after knocking Jules Verne out of the running, Michelino has an epiphany. Realizing that his fault laid in regarding these eight writers as “synonyms of equal truth,” he changes his elimination process, instead ranking them from “the most external to the most internal, from the least true to the truest.” Which truth is weightier: his naively held, eight-sided truth, or the impending discovery of the truest writer?

After more dismissals, it is settled that Conrad and Stevenson will vie, and the winner will face Melville. The two writers’ oeuvres are fantastically placed on opposite pans of a scale: Heart of Darkness, Lord Jim, Typhoon, and five of Conrad’s other works are set on the right side, while only Michelino’s annotated copy of Treasure Island is placed on the left side. The scale makes its judgment and raises Stevenson’s pan above Conrad’s—embedded as the former is with Michelino’s personal history—but Melville is finally named the victor.

Another element to “Eight Writers” is its satirical spin on collecting. The story pokes fun at the contemporary attempts to collate and compartmentalize literature as seen through the canon wars, the ceaseless attempts to rank literature, and the current viewing of literary heavyweights. Michelino’s canon has its own internal pressures; it caves in on itself when the line between genre and style is blurred, erasing any individuality among the eight writers. Today, merely a quarter into the century, the New York Times set out to define the best books published since 2000, and The Atlantic too placed their picks for the best American novels into the confines of a list. As rampant disagreement spread in the wake of these compilations, the overwhelming winner seems to be, at the end of the day, personal preference. Our bookshelves are not makeshift colosseums that set the battleground for Jane Austen to spar with the likes of Vladimir Nabokov or James Joyce with Toni Morrison. Rather, our books are vessels of our selves.

*

Was it Benjamin or Mari who wrote that “ownership is the most intimate relationship that one can have to objects”? Benjamin believed that books are sources of existence, with a lifeblood of their own: “Not that they come alive in him; it is he who lives in them.” He closes his essay on collecting with the image of a dwelling constructed with “books as building stones.” This abode, strung with memories (perhaps a mix of cozy and startling), is a place Benjamin wants to get lost inside of. The epitome of well-being, for him, is to carry on an existence “in the mask of Spitzweg’s ‘Bookworm.’” Mari’s dwellings subvert this image into one teeming with the grotesque—the effect of an insatiable literary appetite. Somewhere in between Spitzweg’s “Bookworm” and Gustave Doré’s Inferno illustrations, both Michelinos sit tethered to their bookshelves.

Francesca Mancino is an English PhD student at CUNY’s Graduate Center. She occasionally interviews for Five Books and her most recent work was published in The Atlantic.

******

Read more on the Asymptote blog: