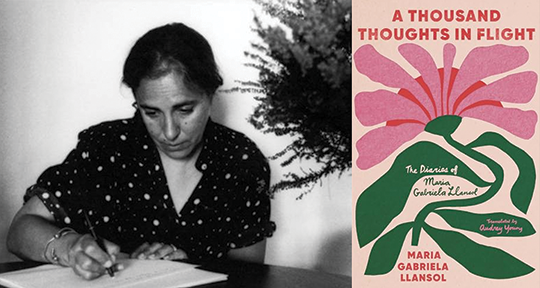

A Thousand Thoughts in Flight by Maria Gabriela Llansol, translated from the Portuguese by Audrey Young, Deep Vellum, 2024

A Thousand Thoughts in Flight, the diaries of Portuguese writer Maria Gabriela Llansol, is divided into three sections: “Finita”, “A Falcon in My Wrist”, and “Inquiry into the Four Confidences”. Comprised of three books from the seventies that Llansol left behind when she passed away in 2008, these volumes were the only ones to be published in Portuguese during the writer’s life, and are also the first of her non-fiction writings to appear in English, thanks to the work of translator Audrey Young. In his introduction, the critic João Barrento describes these private texts as “osmotic diaries: their genesis, their development, and their final form are inseparable from Llansol’s other books, which always accompany them and are interwoven with them”. This is true not only in the conceptual but also the literal sense; the first diary begins the day she finishes The Book of Communities—the first volume in her acclaimed trilogy Geography of Rebels—and ends the day she finishes The Remaining Life, the second volume, in 1977. The second diary picks up when she is finishing In the House of July and August, the final volume, and beginning to write her second trilogy, while also providing glimpses at the author brainstorming her duology, Lisbonleipzig.

Llansol is a generous and poetic writer, sensual in her descriptions and intensely attuned to the metaphysical and the otherworldly, coalescing history, philosophy, and physical experience; these qualities are boldly apparent in her fiction, but appear with an experimental and kinetic mode in these diaries. A common thread across the volumes is silence: everything that remains in the journal is a “draft”, consisting of left-out pieces and vacant spaces for contemplation, and this attention and appreciation reserved for emptiness becomes integral to the diaries’ form. Silence manifests in the common use of gaps in the text, indicated in certain places by a horizontal line (________), and more compellingly in other places as unannounced fragments of poetry. And in between these fragments is life. She moves all around Belgium, from Louvain to Jodoigne and finally to Herbais, where she and her husband Augusto Joaquim run an experimental school as part of a cooperative—which also makes and sells furniture and food. There, Llansol cultivates her own garden, which provides a bouquet of scenes and observations for her diaries, and immerses herself in music. Still, she never pauses in her pursuit of literature, of writing and reading about theology, philosophy, the lives of poets and mystics. It is only in the final diary that she moves back to Portugal’s Sintra, sometime in 1983, remaining there until her death.

All throughout these intimate texts, Llansol makes notations, references, hinting at the broad literary landscape that backgrounds her own writing; she does not simply keep a record of the authors she is reading or translating, but includes them as characters. We also know, by virtue of the way she writes, that Llansol is sincere when says: “I never finish reading most of the books I begin. I become despondent or paralyzed. . . . I am interested in a sentence, a fragment of text, and, very rarely, an entire book, which I read very slowly.” These discontinuities follow in the writer’s treatment of her own life, and though we are given some sense of the unfolding years, the days are not sketched out with any clarity. She maintains distance from the material conditions of her life; we don’t know much about the reasons she left Portugal, her work at the school (although she occasionally provides glimpses at the difficulty of dealing with parents), or the details of her daily life. There are only slight revelations: the garden scenes, the time spent at home with her husband, and occasional meetings with friends. Her extraordinarily rich inner life rarely seems to include effusions of anger or joy while interacting with real people, and her diaries somehow resist autobiography. Instead, as she says in an interview with Graça Vasconcelos, these works are more “about the parallel and mirror creation of certain realities that express my inner mutations of energy”.

Instead of allowing us to trespass into her experiences, Llansol chooses instead to immerse us deeply in scenes from her books and in anecdotes of philosophers and mystics—al-Hallaj, Ibn Arabi, Nietzsche, Spinoza, Emily Dickinson, Virginia Woolf. Were such names not so immediately recognisable, one might actually forget that they are historical figures, so familiar do they become in Llansol’s representation. In the diaries, these monumental individuals are simultaneously larger than life and ordinary—if eccentric—visitors to her private garden. To construct these hyperbolic portrayals and the author’s abstract inner landscape in English, Audrey Young uses unique wordings to consistently reassert the presence of Llansol’s writerly voice, reminding us that despite the author’s wishes for her diaries to exist “objectively”, rising above any material identifiers (social or political), they remain entirely hers. Through them, one can see the resonance of what her husband says about the best hope for their work: that they “leave nothing of ourselves out of our acts, even the most incomprehensible ones”.

Still, the most grounded and compelling sections of Llansol’s diaries are the moments in which she allows the inescapable life-details to take up space. In brief descriptions of the plants in her garden, she says: “I am not writing these notes for anyone, I am writing them for the plants themselves, the names of which I do not know, so that they can take advantage of the fact I know how to write.” Later, she says: “It is essential to write to all things.” But why? In one entry, she explains: “I write in these notebooks so that the experience of time can, in fact, be absorbed. . . . In short, I write in these notebooks so that my body does not stray from the rising line which runs toward old age, as I conceive it: an immense reflection, a loosening obtained from contrasts, a concentration on the present, in which all times imaginable are unfolding forever.” Thus, writing becomes an opportunity to see oneself reflected back in words, in testament, and in the lives of every person/plant/character bringing colour and shade to existence. It is, in a way, to give the self another life through witness—an opportunity, as Ada Limón says in her poem “Sanctuary”: “to be made whole / by being not a witness, / but witnessed”.

But writing is also a refusal to allow time (and life as time) to pass unmarked or unremarked. Elsewhere, she draws a metaphor: “the diary is the cloth with which we clean the years.” Perhaps she means that writing presents an opportunity to erase such years, but from the sheer volume of journals kept throughout her life, it’s more likely that she intends the years to be rewritten. She believes that they can be framed, and experiences can be remembered as if they had gone exactly as one had hoped. We can keep only what we want to remember, lifting certain moments up to dust off neglected recollections, moving things around so they make more sense, and from there, the stories of our lives can read more simply, more meaningfully. In these diaries, she makes herself into a character much like the literary minds she converses with, allowing her written self to exist beyond her actual self, giving that woman her own temporary life. “I write,” Llansol says as she muses on Rilke, “listening, in the faultless illusion, to my own voice.” She continues, making use of the space that thinking necessitates on the page:

I begin to meditate and I conclude that my life’s work encompasses all manner of preparatory tasks,

including

to reconvert myself to an originality,

to steer myself to the same place.

Ruwa Alhayek is a Ph.D. student at Columbia University, studying Arabic poetry and translation in the department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African studies. She received her MFA from the New School in nonfiction, and is currently a social media manager at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog:

- A Metaphysical Mistake: On Elias Canetti’s The Book Against Death

- Great Material for a Novel: Lucy Jones on Translating Brigitte Reimann

- Perpetuating the Original in Translation: An Interview with Ross Benjamin