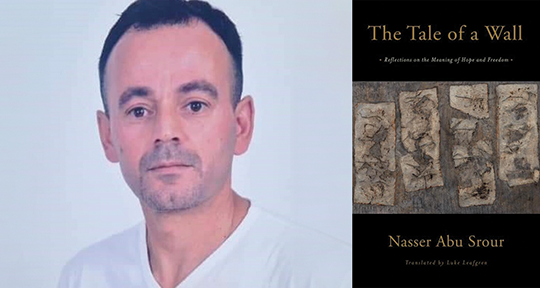

The Tale of a Wall: Reflections on the Meaning of Hope and Freedom by Nasser Abu Srour, translated from the Arabic by Luke Leafgren, Other Press, 2024

In his opening note to the readers of his prison memoir, The Tale of a Wall, Palestinian poet Nasser Abu Srour wishes a “rugged time” to those who are heading into his scintillating prose, a terrain which is also interspersed with charged moments of verse. Indicating that its author is a romantic at heart, this philosophical and nihilist work of mental abstraction was inspired by the “womb of a concrete wall” that has held Abu Srour since 1993, when he was given a life sentence at the age of twenty-three for being an alleged accomplice in the murder of a Shin Bet intelligence officer.

As literature, The Tale of a Wall is a visceral, Dionysian feast of words, lain with a delicate hand. Fired by righteous indignation and howling with a disembodied eccentricity, Palestinian self-determination is here distilled into a single voice, tortured within the echo chambers of a confession table and the paper cuts of intellectualism, finishing with a full course of epistolary melodrama. The memoir itself is cleaved in two, with the first half dedicated to letting go, to saying farewell to the world after his incarceration in Hebron Prison in the last year of the First Intifada. The latter portion is devoted to his relationship with a woman named Nanna, a diaspora Palestinian who returns to her ancestral homeland to capture his heart with a power rivalling that of Israel’s occupying force.

In 1980, Danish photographer Jan Banning captured two Maasai men in traditional attire, holding a copy of George Orwell’s 1984; the image symbolizes the erudite refutation of disenfranchised indigenous people against the postcolonial impositions that have assimilated or annihilated them, and The Tale of a Wall similarly invokes canonical Western philosophy, joining its ideas with the Palestinian struggle. Throughout his prose, Abu Srour diagnoses the unlucky global majority who inhabit a metaphoric wilderness, bludgeoned by the blunt end of Western civilization. In the aftermath of modern warfare, the victor is a Kantian “pure reason” (as in that which is deduced without experience), and against this, the writer trespasses borders and languages through intellectual courage, subjectively examining the West’s project of globalization and exposing its moralist democratization as a ruse for more nefarious motives. This wide-ranging, monologic discourse begins with sentence on Kierkegaard, invoking the patron saint of redeemable suffering:

Two weeks ago, I emerged from an extended bout of apathy and decided to read a book by Kierkegaard. In the book he talks about love, arguing that the best way to preserve it is to release the beloved and to deny all possessive instincts, such as dependency and egotism. He also claimed that this letting go is only possible through the irrationality of faith.

Grappling with belief is a staple motif in prison writing—holding to the buoy of religion so as to stay the long road to liberation. Substantiating this necessity of faith in freedom from the start, Abu Srour delves into a timely memoir of Palestinian bondage, inviting his choir-like readership to review a historical retrospective of Israel’s occupation, contextualizing both Nakbas (1948, 1967) and Intifadas (1987-90, 2000-05) through a resigned, more stoical gaze than that which the current Gaza-born stream of moral outrage might deploy. And as is evident in his forward-moving tone, throughout the devastating wars and conflicts, what remains steadfast is the human tendency for hope, the conviction that change will come.

Unlike more temperate testimonies that might attempt a balance between the late political resistance of Yasser Arafat (whose alleged assassination Abu Srour unquestioningly affirms) and the militant Hamas, The Tale of the Wall is more so a nonpartisan expression of human passion. Readers following Abu Srour’s careful, poetic proclamations of his confined self will find a meditation on the gravity of life, spent not only in the condition of statelessness, but also joined to an identity starkly defined by loss. Movingly, he describes the mentality of being stripped of everything but his being, finally submitting not to the bare austerity of his solitude but the meditative, poetic ruins of his existential consciousness.

One minute you are master of your domain, which you fill with your own words and meanings. The next you are held hostage to an alphabet invented in some other time, for someone else’s purposes. Then all your wondering gets buried deep inside you, your questions turn into doubts, your doubt becomes error, and your erring bursts into a flame from which you cannot escape. You are lost in the darkness of past eras that refuse to end. You are enveloped by the gloom of cultures that possess no sun to illuminate their darkness, no moon to give them beauty.

These passages—and many following a similar pulse—run the gamut of non-specificity, cleansed of the temporal or geographical details that might narrow their subject into the gravity of a greater whole. But Abu Srour exercises a poet’s iteration of prose, gliding towards the mystic wonders of his undivided, individual experience. The question of his mere survival is almost backgrounded by his testaments of the mind’s capaciousness.

As the mind ranges, however, the body remains static. Mirroring the loss of land with the state of confinement, The Tale of a Wall posits that rootlessness is also instantiated by setting a prisoner into the stone of spatial intractability; his immovability runs contrary to modern settlements, be they towns, cities, or nations, in which occupancy is also defined by a personal freedom to traverse borders—most importantly one’s own. National citizenry is not merely defined by domestic rights but by the prevailing world order, one in which Palestinians, among other stateless peoples, have yet to gain formal recognition vis-à-vis the United Nations. The enjoyment of unrestricted, individual movement is essential to free human settlement, however conditioned by geopolitical relations and economic ties; statelessness, on the other hand, is purgatorial, be it in the form of open-air ghettos, colonial subjection, concentration camps, or settler occupation. Abu Srour expresses such resignations before Israeli injustices with the conviction of a survivor, beginning his chapter, “Solitary Confinement” by stating the following:

Don’t set your roots too deep in any world you inhabit. That only makes the pain worse when they are torn out.

With artistic abandon, Abu Srour applies these learnings to the cause of the Palestinian struggle, recalling his adherence to the various and mutable movements that have overlapped with his upbringing and his life in prison, while noting how his three decades of imprisonment has disillusioned him of all that he’d identified with in the past. Ultimately, the terror and despair of being born on occupied Palestinian land—navigating the mutual hatreds between Jewish supremacists and stateless nationalists—consumes him as much psychically as it does physically. Since he was first jailed at age sixteen, Abu Srour has never enjoyed an adult right to agency. He is, instead, transferred between nine prisons through the busta, “an iron beast of a transport vehicle.” Through its small metal holes, he only glances at the changes in the terrain he’d been fighting for, an ongoing resistance that is just out of reach. There remain moments, however, when he implies that simply remaining alive is to sustain the spirit of Palestinian liberation; the Israeli authorities’ decision to place him in solitary confinement is interpreted with some pride: “I still posed a risk to their dreams.”

In the chapter, “Starvation,” Abu Srour shows just how well he maneuvers in the crawlspace of the pernicious, occupying mentality, which has sought to displace Palestinians not only from the will of their own bodies, but of their intellectual camaraderie to unite as a sovereign, national identity. Prisoners hit back with hunger strikes and other, self-destructive resistance tactics; as true existentialists, they know that their greatest power lies in simply choosing to be, or not. These actions are placed directly within the historical and psychological backdrop, iterated with the clarity of an insider:

Using old prisons left behind by the British Mandate authorities and building upon the ruins of the two nakbas, the Occupying State constructed numerous prison camps that began to be filled after 1967 with young people whose social consciousness was not yet fully formed, even if their pain and feelings of loss were fully developed. These young people fought and were killed, or they fought and were cast into the gloom of the prisons.

With perspicacious commentary on greater world affairs, Abu Srour shows how many of these acts and their response from the authorities run parallel with concurrent political events such as the First Gulf War. This contextualization of Israeli and Palestinian agendas is lucid and meticulous, tracing the conflict as it increasingly spirals outward to encompass broader regional and global struggles. Thus, when The Tale of a Wall introduces the interpersonal love story that spans the latter half of the book, it is with a transnational consciousness that the reader meets Nanna, who, was “planning her first steps and picking up the first thread of blood” at a time when Abu Srour was desperately resisting the urge to surrender his body.

He brings her into the story by first detailing her childhood and education—specifically her choice to study law and to apply this work to the cause of Palestinian liberation:

Her opposition to the judiciary of the Occupying State increased as her awareness of its injustice grew. As the Occupying State hardened its policies toward the Palestinian minority, Nanna’s questions about her identity became all the more insistent. . . .

Nanna’s first years after returning to her town, located within lands occupied in 1948, were accompanied by news and stories about an ancient wound that were recounted whenever families gathered and conversed.

When he first sees Nanna, the sight of her face is emancipatory. The inspiration of new love allows him sufficient insight and repose to contemplate the seed of his aspirations, to merge the personal pursuits of freedom with the collective liberty of all Palestinians. Humanity comes closer to him in her presence, as she lures him toward a measure of hope that would have otherwise remained beyond his reach; she grants him a possibility of love, which promises to be as challenging and fulfilling as any other fathomable sense of purpose.

When her weekly in-person visits prove insufficient, the two resort to writing. What follows is the magic potency of the written word, a monologue transformed into a dialogue, Socratic in its commitment to universal ethics, unfolding outward from their deepest emotions and allowing them a reprieve of private intimacy. In the first of her many letters, Nanna articulates her conviction that Palestinians deserve the same degree of political power and personal freedom that children born in any modern nation would enjoy. Conveying the chemistry of their intellectually-inspired romance, their words are fired by the social urgency of their common ideals.

I’m a naturalist in an unnatural reality, and I need to meet supernatural people like you in order to preserve the balance of my nature.

So happy I’ve met you,

Nanna

In invoking this continual desire for connection, Abu Srour reaches beyond the spells of madness that war fuels within unending cycles of vengeance and trauma. His is a voice that has matured alongside the growing pains of the world, which still struggles to bear the responsibilities of its past. Defying the imposition of silence as a child of the Generation of the Stones, The Tale of a Wall convokes a succession of cries that will not fade in the dying light.

With the characteristic grit of his emotional intelligence, buried under multigenerational bonds of chauvinistic enmity, Abu Srour summons the mental strength to proceed, outwardly, toward a broader vision of his struggle—not solely his own, but united with the Earth’s outcast victims of systemic hate.

Believing in the universality of oppression and the globalization of poverty was all it took to break free of our provincialisms.

We were not yet twenty years old, yet we devoted ourselves to causes that by now had entered their third millennium. We warred against illusions that debased the human self.

Matt A Hanson is a writer, journalist and editor based in Istanbul. His cultural criticism appears in such outlets as ArtAsiaPacific, World Literature Today, and is forthcoming for History News Network. He has written short fiction for Panorama: The Journal of Travel, Place and Nature, Washington Square Review, and elsewhere. Archives of his writings can be found at his indie literary arts press, FictiveMag.com.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: