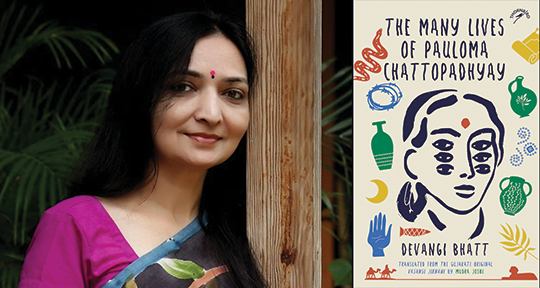

The Many Lives of Pauloma Chattopadhyay by Devangi Bhatt, translated from the Gujarati by Mudra Joshi, Niyogi Books, 2024

In The Many Lives of Pauloma Chattopadhyay, Devangi Bhatt’s novel of fantastic realism, the extraordinary is prefaced by a scenario of extreme normalcy. In Kolkata, Pauloma Chattopadhyay lives out her days as an ordinary middle-aged housewife. Her husband, Nikhil babu, is a civil servant and a man of a few words, set in his routine. Sharing their house are two sons and their families; there is a daughter too, but she is married and hence resides elsewhere. Theirs is a standard joint family and Pauloma is unquestionably the matriarch of the household, but it would be hard to say that she has any power to go along with that position—and even if she did, she is not one to exercise it. All things go about in harmony in house no. 11 with the well-practised dailiness of domesticity, and from the beginning, Bhatt makes it clear that her movements are not curtailed, and nor does she live in a state of unhappiness:

Pauloma is a vivacious woman with an abundant love for life. She likes gossiping with the neighbours, bargaining with the saree seller, watching Bengali plays with her daughters-in-law, and feeding her grandkids sondesh. Though Nikhil babu and Pauloma are very different, it can be safely said that their world provides a sense of stability. Everything has been well for a long time, and there have been no problems.

Stability, however, tends to get stale after a point in time, and even more so for a housewife whose life mostly takes place within four walls. While Pauloma is not exactly crushed by the mundanity, she nevertheless recognises it: “But… but sometimes a strange thought crosses Pauloma’s mind as she sits by the window, rubbing oil on her scalp. . . . As she turns the shell bangle on her wrist, she thinks that life shouldn’t be like a straight line without any exciting deviations.” These short moments are akin to revelation, brief ripples on a still body of water, and it is this feeling of the past slipping through her fingers, of the transience of her life, that sends her to the storeroom in search for her late mother-in-law’s large storage vessels—which have been gathering dust and are set to be sold. On a whim, she climbs into one of them, only to be immediately pulled inwards and magically transported.

The next chapter takes us to Hanover, Germany in 1925. Aurora wakes up on a park bench, disoriented. She is a child enrolled in school, and her family is one of many who are suffering in the downturn and recession of the First World War’s aftermath. Her mother works as a housekeeper for a rich Jewish family, whose comfort is in stark contrast to Aurora’s living conditions, and over time, she grows bitter and jealous as she imbibes antisemitic German propaganda, eventually becoming an unquestioning supporter of Nazism and the eradication of Jews in the service of the German nation. She gets married to her childhood friend who, despite his steady climb within the military, is not convinced by the populist opinions, growing increasingly disillusioned by the state machinery and its stated goals. We follow them from Hanover to Dachau to Auschwitz, until Aurora’s death. Through it all, the prose encourages us to see her as a strong woman of conviction and action who has been terribly misled—one who is resolute to live life on her own terms without giving into others’ demands.

When Pauloma regains consciousness back in Kolkata in 2016, she finds that only ten minutes have passed. The whole experience has been incredibly perplexing for her, and she tries to shake it off by resuming her routine. She avoids going into the storeroom for months until one night, during Durga Puja, she finds herself alone in the house and the temptation overtakes her. She is pulled into the past again, and in this excursion, we follow Rabiya Abdi, an Egyptian princess, living in 1950s Cairo. The second wife of a prince, she is a sheltered, young, childless woman who has known no life outside of the many comforts of royalty. However, while she is modest and conservative, she is not meek, coming out of her shell when a brash, irreligious, and womanising famous painter grudgingly accepts the job of painting her (along with other members of the royal family). She falls in love with him and is willing to abandon her previously held convictions, but that love is not reciprocated and they part. This narrative again ends with her death some fifteen years later after she runs into the painter accidentally in London, and he still rebuffs her advances.

For Pauloma, the second time is even more harrowing: “It appeared that [she] had lost her mind since Durga Puja. She would not hear when people called, would speak the most absurd things, and sometimes she would go blank and stare into space as if the world around her did not touch her.” As a result, she is taken to doctors and her responsibilities in the house are reduced. Months pass. Once again, she is all alone in the house, and once again, she gives in to the beckoning voice of the vessels. This time, she is whisked off to 1955 in Velsar, Gujarat—a small village in Saurashtra. The TV announces that the apocalypse is coming on the next full moon and all the villagers get into preparation mode. We follow Monghi, a young married woman who is quick to anger and headstrong; her wrath is famous in the entire village. While the villagers either make merry during the end times or repent strenuously for their sins, she single-mindedly seeks out the village goon, who has ignored her ever since she had reprimanded him in public, wanting him to acknowledge her as a desirable woman.

What remains in doubt is the nature of these “visitations”. Pauloma is not inhabiting their bodies; her point of view is not present in any of the three historical narratives, and it is also difficult to define it as a case of Pauloma experiencing her past lives, as the three women live in overlapping time periods. Neither does Bhatt provide any clear-cut narratives from one death to another birth that would prove the existence of a cycle. When Pauloma shares her experiences with the people close to her, they can only dismiss them as delusions; when it keeps happening, she is taken to doctors and diagnosed. We do not really hear from her after the third incident, receiving only an update in the last chapter, set in a university psychiatry class almost a decade into the future, in which the professor brings her up in a lecture on delusions: “She became completely untethered from reality. She stopped speaking to everyone and remained shut in her room. She passed away a few years later in the same condition.” Essentially, Pauloma is fated to fade away.

In Bhatt’s fabulistic mode, the focus on illuminating the lives that Pauloma could have lived takes away attention from her actual life—a double effacement. She is invisible within her family, and then further invisibilised through these travels in space-time. The three narratives take up considerable space in a novel that is already quite short at under two hundred pages, and the amount of attention given to Pauloma in the present would not even amount to two dozen pages altogether. While it is true that her current life is one of staid, unassuming domesticity, there would still be merit in exploring her interiority and fleshing out her character. In fact, that would have more strongly exhibited the complexity of her personhood and established her voice in opposition to her sustained, benign marginalisation as a family fixture. Domestic bliss is clearly not as it seems, as there is still room for dissatisfaction and silent rebellions against complacency; Pauloma might be content with her life, but this contentment hides a restless subconscious, a hungry mind.

No wonder then that the critic Mihir Bhuta, in his foreword, comments: “This peculiar style of storytelling makes the protagonist a symbol herself. Deep symbolism is the core of this novel.” The overarching idea of enforced silences encapsulates the divergent strands of the book, as Pauloma remains a symbol for the inherent repression in patriarchal domesticity, and never becomes a living woman with overt aspirations. Still, Bhatt’s vision is interesting—a transmutation of a sort for her titular character, and while the locations and time periods of these three narratives seem random, the other women all possess qualities that Pauloma seems to be lacking. They are not simply strong-willed, but lead eventful lives in very different socio-economic contexts, quite divorced from Pauloma’s current circumstances. Perhaps they are the catalyst for a realisation about what life could be. Perhaps they are well-needed breaks from mundanity. Perhaps it’s actually Pauloma losing touch of reality. It is this unresolved mystery, and the sad truth of the protagonist’s life—as well as the lives of the three women she embodies—that fill the pages of Devangi Bhatt’s novel with pathos.

Areeb Ahmad is editor-at-large for India at Asymptote and books editor at Inklette Magazine. Most of his writing can be found on his bookstagram, a true labour of love. Their reviews and essays have appeared in Scroll, The Chakkar, The Federal, Hindustan Times, and elsewhere.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: