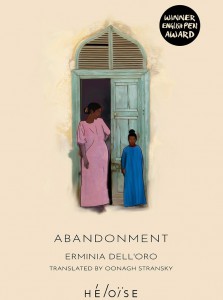

For her translation of Erminia Dell’Oro’s Abandonment, Oonagh Stransky received one of the prestigious PEN Translates awards in 2023; one year later, this powerful, lyrical novel is due to arrive by way of Héloïse Press on September 15. Rendered into English with great sensitivity and intimacy, Abandonment tells the story of a mother-daughter pairing in Eritrea, and their alienation from both local and the colonial Italian communities in the aftermath of racial laws. Stransky fought for its appearance in the English-language for twenty years, and in the following essay, she speaks on the emotional, introspective process of translating this tremendous work, and why she has remained so determined that the world should read it.

It’s July 2024, and I’ve received the proofreader’s notes for Abandonment. I need to reply to an issue with the passage below:

“Then Sellass felt a deep languor come over her and she understood that her body was dissolving into the seawater, that the wave she had become was returning towards the light and slowly breaking on a beach where the shades of the dead had gathered. Even Mariam’s shells were there, specks of darkness on the sand, and a hand reached out to grab them. The wave tried to speak, to tell her that she was Sellass, but the voice was only a watery gurgle, and the shades, going through the gestures of life, ignored the coming and going of the wave.”

The proofreader says

This is a bit confusing—reads to me like the wave is speaking to Sellass, but if I’ve understood correctly the wave IS Sellass? And she’s trying to speak to Mariam? I think the confusion is using “she” to refer to the wave, if it read ‘to tell her that it was Sellass’ it would be clearer.

I reply

Using “it” does fix the problem but ambiguity and the gendering of the wave are important to both story and style. Actually, the original Italian doesn’t say that the wave is trying to speak to Mariam. It just says, L’onda tentava di parlare, di raccontare che lei era Sellass. . . I suggest modifying that line to: The wave tried to speak, to say she was Sellass. . . This keeps the female gender of the wave and retains an element of ambiguity.

In my dreams I reply like this

The world of this book is filled with objects that we readers might commonly see as neutral but that are attributed gender by characters who need them to survive, who see their fragile lives building and then crumbling, over and over, casually, randomly, like waves. Sellass in this instance is indeed the wave, and because the wave in Italian is a feminine noun, she is both wave and girl. More than trying to address Mariam here, Sellass is receiving a message from the universe that she is a mere mortal, that she coexists with death, with the shades. Her daughter, Marianna, will be made aware of her own mortality, but she is accepting of it, which in turn allows her to survive and not become a victim; this awareness is the key to her resistance.

A bad reply

Once, while participating in a panel on translation a few years ago, an intelligent young graduate student in the audience asked me if I saw translation as an act of resistance. No, I said awkwardly and suddenly felt shame because up until then, I had given little or no thought to the matter.

Reply: from the Latin re- (again, back) + plicare (to bend, to fold)

If asked now, I would reply

Choosing to translate Abandonment does not represent just another notch on my belt; it constitutes a major act of resistance. I first read the book in 2002. I met the author in 2003. I told her I would find a home for the book, and, over the years, pitched it to a number of publishers. Mainstream editors turned it down because they didn’t see how it fit in; academic presses said they had no money for it. Then I heard about Héloïse, a small British press that focuses on translated literature by women. The editor saw this book for what it is: a counternarrative, a story of a mother and daughter relationship where pressures of history and circumstance crush the mother and trouble the daughter, but ultimately inspire the younger one to stay true to herself, to forge a path, to exist outside of what we generally consider the margins to be. Although Marianna grows up in extreme poverty, abused, and discriminated against from all sides, she does not give in. She is a fighter, and I guess I consider myself one too—fighting for books, for words.

But when I read, I bend and fold to my feelings

Have you ever read a book that both guts you and replenishes you at the same time? When a book says to you: yes, this is how it was for you, too, even though you share nothing tangible or material with the protagonist, even though you appear to exist worlds apart. You are connected to the protagonist by words, tied to the page with her, the two of you are imprisoned by words, and yet words are your only way out. . . That’s how I read: visceral first, analytic later.

One more time with feeling

When I first read Erminia Dell’Oro’s L’abbandono, I had the impression that I had in my hands a dark wooden jewelry box, delicately carved, inlaid with mother of pearl and grit, lined with something fragrant like sandalwood or cinnamon bark. The story was the treasure. I remember wondering if I had stumbled across a text that had been long lost to humanity, now found. On remembering that moment, the word atavistic comes to mind.

Translation as reply

In the same way that Marianna made her way to Italy, the land of her absent parent, to both find and make more of herself, I did the same after graduating from college, in 1989. Just as Marianna lived and learned, loved and had children, so did I. And while I was on a hunt for meaning that I may not have even fully realized I was on, I found translation. Or maybe it found me. Either way, it too is a kind of reply—to the call of literature, the call of writing—a reply that unifies, spreads ideas, grows readers, shares stories, and helps a girl transcend.

A reply does not have to com-plicate, it can be an unfolding

There’s another reason why I chose this book, or why it chose me, and it is a personal one. I do not belong to a colonized people, I have not known discrimination, my struggles have not been with poverty—but nor have I been the colonizer. What I like about Marianna, the reason her story resonates so deeply with me, the reason I have stood by this book for twenty years (as anyone who knows me will confirm), is how she willfully committed to improving her situation, how she stepped away from the parent she tried to love and radically shifted the axis of her existence towards the parent who abandoned her, who in turn had been incapable of reconnecting with her for so many reasons. Her personal drama mirrors my own. But that is a story for other pages. Let’s just say here that Marianna inspired me to pursue my own path.

Oonagh Stransky has translated the work of Domenico Starnone, Eugenio Montale, Carlo Lucarelli, Giuseppe Pontiggia, Roberto Saviano, and Pope Francis. Her personal essays about the craft have appeared on the Hopscotch website and in Tupelo Quarterly. She is currently writing a memoir in essay form that opens a window onto her connection with the Italian language and the strange, officinal powers of translation. www.oonaghstransky.com

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: