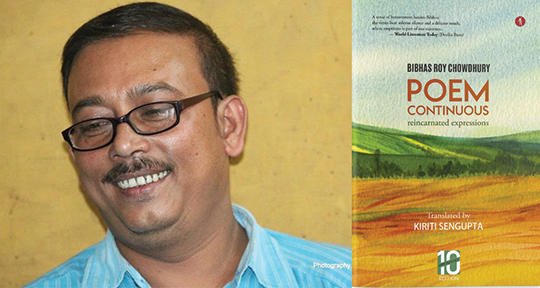

Poem Continuous: Reincarnated Expressions by Bibhas Roy Chowdhury, translated from Bengali by Kiriti Sengupta, Hawakal Publishers, 2024

In The Anxiety of Influence, Harold Bloom writes: “Poetic Influence—when it involves two strong, authentic poets—always proceeds by a misreading of the prior poet, an act of creative correction that is actually and necessarily a misinterpretation.” According to Bloom’s theory, the authentic poet stands in relation to poets of the past, and this relationship to tradition is a creative force, which Bloom calls “misprision.” In the instance of Bibhas Roy Chowdhury’s Poem Continuous: Reincarnated Expressions, the traditional poet is Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore.

Both Roy Chowdhury and Tagore suffered from the Partition of Bengal by the British; in 1905, Tagore used Raksha Bandhan to unite Hindus and Muslims against the Partition, whereas Roy Chowdhury’s family lost their wealth, and upon the later division of Bangladesh in 1947, became refugees and common laborers. Throughout many of these poems, translated by Kiriti Sengupta, Roy Chowdhury laments this predicament, coalescing the historic developments with his father’s death. “True and False for My Father” reads:

I’ll say

(if I’m honest):

after my father’s demise

I found myself duty-bound

in the crematorium—

not from being his eldest son,

like an event manager, rather.I didn’t perform his last rites.

I followed no ritual

nor did I take part in the funeral.Someone remarked:

You are indeed

an ideal communist.

Rabindranath Tagore echoes these sentiments in Gitanjali 35, conceiving the father metaphorically in relation to the Partition: “Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action—Into that heaven of freedom, my father, let my country awake.” In this quotation, the father is the actualization of humane and unifying action, and in Roy Chowdhury’s poem, the father is represented as a procession between generations. The latter’s relationship with his father is deepened to metaphor in “True and False for My Father,” and is carried on to other poems such as “My Little Girl”: “Life is like a father. / I even tell my daughter—fight. / O poem, fight. / Forget food and water, and fight!” By equating the poem with his daughter, the poet confounds them, suggesting that poetry is birthed from sacrifice.

Whereas the father represents force and dominion (“Fathers rule. No one forgives the faults / of a ruler!”), the mother is a figure of fusion and nurture—the rain in “Birth of a Legend,” representing a restoration:

We overheard and understood

Ma got a nickname: Rain.We noticed our father remained

engrossed during the monsoon;

he passed away in the last autumn.

The demise of the father highlights the poem’s ingrained grief, and paves the way for a further exploration of absence; Roy Chowdhury selects not to elect his mother’s presence, instead evoking her through lament. “Our undressed mother; / leaving her children behind, / where did she go away? / Mysterious rain arrived / after a few days; / Ma never returned.”

Where, then, can one find the misprision of the anxiety of influence? In Tagore’s writing, the Partition is seen as a way by which the poet explores the tenets of human nature: “Our nature is obscured by work done by the compulsion of want or fear. The mother reveals herself in the service of her children, so our true freedom is not the freedom from action but freedom in action, which can only be attained in the work of love.” Tagore isolates anger as a setback from his spiritual path. Roy Chowdhury, then, writes in “The Blaze”: “The earth has its share of dust, / and the transferable odor of lonely madmen.” Madness is seen as part and parcel of nature, the frenzy which births its own destruction. Later, in “I Can Leave, but Why,” he writes, “Men are under fire, and I can sense / the heat of destruction. / Will these plants exist even after my demise?” This echoes the previous sentiments of “The Blaze,” as the fire speaks and promises not to harm creation. Creative destruction is ingrained within nature’s order in Roy Chowdhury’s poem, and poetry is his resistance against both Partition and reconciliation, with their respective violent histories.

In “The Sun-Burned Ashes,” Roy Chowdhury conflates the fire of the sun with his being:

Sun, what is there beneath your dazzle?

Merely burned ashes, right?

Sun, in this birth of my being

let me enter you inside.My poems blaze—

how much of this knows the script?

This conversational method illumines the poem’s propelling sentiment; the poet addresses the sun with his desire to “enter,” and the poems also “blaze,” merging the work with the writer’s own internal conflagrations. Is the poem implying the poet’s birth as “burned ashes” as the poems “blaze”? Does the poet suggest a predestination of poetry? Or is he suggesting that too much scrutiny will encroach on the poem? When the poem eventually turns to a direct address to the reader—“Reader, do you know I flare in your critique?”—that burning communicates the poet’s sensitivity to interpretation, barring the reader from further elucidations. He defends his solitude as he does in “Being”: “Why couldn’t I become much lonelier?” Known as a private person rather than a public figure, the above dialogue with the reader heightens the poet’s despondency, embracing the futility of the reader’s understanding the intensity of the verses. In an essay excerpted within the volume, Roy Chowdhury states: “Experienced critics bring out the innermost side of the poet through their meditating minds. A few of them challenge the poet and negate his/her poetics, while others greet with their appreciation. . . I think, poets are not celebrities as made by the big publishing houses.”

In these poems, Roy Chowdhury’s anxiety of influence also ventures into metapoetics. By asserting the tradition of Tagore’s love of landscape and family, the poet invites questioning eyes to his craft, coalescing personal history with symbolic expressions. In “The Debt,” he writes, “Look, your kisses fly away to the cloud, / and your hug enables a child to identify a bird.” The seeing of the bird by the child represents a momentary hope, while “the world is approaching its end on a daily basis.” Birds are quickly taken from our vision, as in “Poets and Poems,” where the bird has broken wings yet is construed as the “cursed” poet; mortality is raw and quickly comes to readers and poets alike, uniting them while the horizon expects a promise to be made: “This is the time to make a promise. / To whom and whose words shall I give? / Impossible it seems without the dreams. / Every poem is committed to deliver a promise.”

What could this promise be? The poem’s final line is, “The relation keeps mum thereafter.” In his notes, Sengupta quotes Joy Goswami’s comments on “Epitaph”: “The relationship between the poet and the reader does not end as the poet dies. This relationship is dynamic!” The promise is the immortal continuation of the poem, via the form of the book.

In Roy Chowdhury’s writing, one finds many mysteries and thoughtful riddles. Sengupta’s translation renders the Bengali into conversational simplicity, yet the unfolding mystery is intact. As I read, I am met with a style in which simplicity is the key to its overall effect—each poem is compact in its rendering from the musical language of Bengali, and the starkest component of each is the ease of their readability. They flow into one another gracefully without violating their autonomy, intertwining their themes without clashing. As Roy Chowdhury says of translation, “Poetry remains localized within the domain of the concerned language,” and Sengupta’s iterations take this to heart, making use of concise lingual units that are easily recognizable across English readership, rather than applying a large vocabulary that hinders interpretation. Ending with an interview between the poet and translator, Poem Continuous offers further insight into the poet’s appreciation and doubts concerning translations, and the original foreword by Don Martin from the 2015 edition highlights the ongoing illuminations of these poems as they find new readers, noting that the translator sees the art of translation as “transition,” and it is in this fresh approach that “Dr. Sengupta translates the whole gestalt of the poem, rather than just the individual words.”

By inviting Poem Continuous: Reincarnated Expressions into the anxiety of influence, the intention is not to conflate Tagore and Roy Chowdhury. Rather, by placing them historically on similar paths, each poet’s works are rendered as their own acts of love and protest, engaging the Partition through the lens of their own personal histories. Father and mother are separate regions of being, while the poem itself is the perpetuating motion of the poet toward his readers. In this collection, Roy Chowdhury allows poetic space for his private life, exposing his innermost pain and confusion to readers and showing that poetry can be committed without invoking an agenda, and as such, the poems liberate the intimately personal from political constraints while embracing historical reality, demonstrating how the Partition continues to inflict suffering after nearly eighty years since its initiation.

Dustin Pickering is founder of Transcendent Zero Press. He has contributed writing to Huffington Post, Los Angeles Review, The Statesman (India), Journal of Liberty, International Affairs, The Colorado Review, World Literature Today, and several other publications. He is author of numerous poetry collections and books, including Salt and Sorrow. He placed in the top 100 for the erbacce prize in 2021 and 2023, and was a finalist in Adelaide Literary Journal’s first short fiction contest. He was longlisted for the Rahim Karim World Prize in 2022 and given the honor of Knight of World Peace by the World Institute for Peace that same year. He hosts the popular interview series World Inkers Network on YouTube, and co-founded World Inkers Printing and Publishing.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: