Yoko Tawada’s latest novel, Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel, presents us with the anatomy of a mind consumed by passion for a dead poet’s oeuvre. Ostensibly narrating the tale of a literary scholar mired in pandemic-era depression, the text expands into a reflection on various forms of friendship—and, one might venture, redemption—that might inhere between readers. At the same time, Tawada deftly traverses voice and perspective to meditate on language as pastiche, ventriloquizing another’s words within the space of one’s own consciousness. With this mysterious work, the German-Japanese author furthers her interest in questions of alienation and affinity across interpersonal, cultural, and temporal realms—polyvocal inheritances that are evocatively staged in Susan Bernofsky’s layered translation from the German. To enact and pay tribute to Tawada’s dialogic style through the spirit of collaboration, Blog Editor Xiao Yue Shan and Assistant Managing Editor Alex Tan decided—for the first time in the Asymptote Book Club’s history—to co-write this following review.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

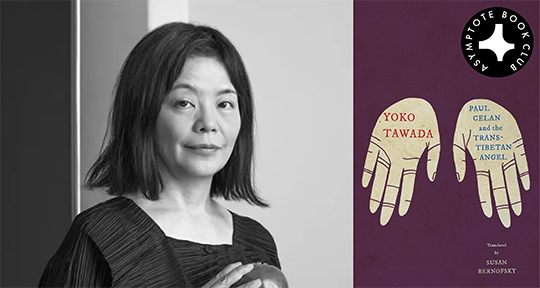

Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel by Yoko Tawada, translated from the German by Susan Bernofsky, New Directions (US) and Dialogue Books (UK), 2024

Paul Celan’s is a poetry riddled with hiatus and dislocation. Words are condensed into weighty German compounds or displaced into shreds, as if in a dream; adverbs are turned into nouns, and pronouns and prefixes are broken off, left stranded on the blank page. In the shadow of the Holocaust, his language concurrently reached for and estranged the singularity of experience, resulting in a body of work that yearns for nothing so much as silence—for that which writing itself would annul: something “absolutely untouched by language,” in philosopher Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe’s phrase. Poetry, as gesture, becomes nothing but the contour of an intention to speak, against which presence is felt only as a silhouette.

For the writer Yoko Tawada, Celan’s poems are less storehouses than “openings,” thresholds onto the inexpressible. What she gravitates toward, in the compact verse, is everything that resists and goes beyond the flatly nationalistic, the “typically German.” In her own literary production, she toggles adroitly between German and Japanese, writing across the two; her earlier novel The Naked Eye, for instance, was originally composed in both languages. Not only does Tawada seek unanticipated constellations of affinity with the foreign, she also refutes the common instinct to read literary texts for ethnographic value, consistently underscoring the mutability of selfhood, its unfixed boundaries.

Her latest novel, the pandemic-inflected Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel, draws on the surrealist toolbox to sketch a solipsistic, obsessive mind haunted by Celan’s turns of phrase, floating through the ghostly streets of Berlin. Imprisoned in alienation and “intermission-loneliness,” he is known to us initially as “the patient,” his identity tethered to an unspecified malady. His name Patrik arrives almost as an afterthought several pages in, amid scrambled reflections on the pronouns with which he designates himself in his interior soliloquies. In his vacillations between the first person and third person, he is perhaps heart-sick, struggling to survive and bear with the burden of himself: “Opening hurts. Closing brings comfort.”

Patrik is a scholar who has chosen Celan as his specialty, and the only aspect of the narrative that resembles something like traditional plot is his decision to not attend a Paul Celan conference in Paris about his nationality (for purely logistical purposes of institutional funding). Immediately this strikes something of a nerve, and with all of its various tributaries, Patrik sums up the strange inadequacy of human infrastructure—across both physical and lingual realms—to contain something as capacious and ineffable as identity: “I’m speaking of liquidity.” His Celan-fixation seems the only solid ground on which he can stand; all the other facts of his biography—the therapist who committed suicide, the girlfriend he may or may not have broken up with, his Ukrainian parents—are consigned to appearing in hallucinatory flashes.

The titular “trans-Tibetan angel” will arrive in the second chapter, bearing the name of Leo-Eric Fu and claiming to be the descendant of a traditional Chinese medicine practitioner from Paris. The reader on a hunt for clues may be tempted to read this figure as a manifestation of Celan himself, based on the name being a mix of Leo Antschel and Eric Celan (father and son of the poet, respectively), but the encounter between Patrik and his angel is much more intimate and sacred than that between an academic and his subject. It is also somehow much more incidental and, for that reason, inexplicable: how does Leo-Eric Fu somehow intuit all of Patrik’s secret cares and respond with such uncanny attunement to his idiosyncratic wavelengths?

The gift of Leo-Eric’s companionship is to lend “wings” to Patrik’s wandering thoughts, so that their exchange feels like “long-distance travel,” a virtual substitute for the conference. In the long talks that issue forth from their common intimacy with Celan, the spatial metaphor further encompasses one of the most tortuous fascinations of conversation: that words do not arrive at their destination intact, but are received as puppets of what Nathalie Sarraute called “inner movements, of which dialogue is merely the outcome.” Language-acts might never allow us unimpeded access into one another’s minds, but they can, in their most animated incarnations, inspire in two people a sense of inhabiting the same world—patterned as if along the line breaks of the same poem. Side by side, Patrik’s hand and Leo-Eric’s hand “aren’t genetically related but resemble one another all the same because they’re both copies of the hand of God.” Subterranean, enfleshed in the hidden soul of language’s void: is it any wonder that Celan, in a letter to Hans Bender, declared that he could not “see any basic difference between a handshake and a poem”?

Claudia Rankine, in her Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, glosses this mutuality as a simultaneous assertion of presence and an offering of that presence to the other; both “I am here” and “here you are.” The poem “intends another, needs this other,” utters Celan in “The Meridian,” a speech that would come to be read as his ars poetica, and Tawada in turn enacts—in her very indebtedness to Celan—a relation unbound by strict filiation, emancipated by its proximity to poetic form. Conversation, for Tawada as for Patrik, might be nothing more than poetic affinity with the otherness of a “you”.

But this otherness, in Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel, is delineated on a cross-continental scale. It transcends the usual Western suspects—Franz Kafka, Emily Dickinson, Guillaume Apollinaire, who all exerted influence over Celan’s style—to encompass convergences between traditions that might never have met. What emerges is a colloquy between a literary legacy and its transnational manifestations—how a past titan of language comes to dialogue with its many various heirs in the present moment, upon the extant page, which Tawada seems to conceive with only liquid definitions. Hence Leo-Eric can speculatively juxtapose Jewish mysticism with Eastern epistemologies of the body, triggering in Patrik free-wheeling associations: just as Chinese acupuncture identifies twelve meridians or pathways through which flow the energies of life, Kabbalah matches twelve letters of the alphabet with organs of the body.

Invisible correspondences triangulate between the embodied and the geographical; Celan’s famous meridian comes to assume proportions beyond itself, overlaid by the ley lines of acupuncture. Previously unseen, a new network comes to hand, by which Patrik can make sense of sequestered parts. Heart, throat, brain, eye; the Ukrainian-German and the trans-Tibetan, all constellated now by the heart meridian. Though these interrelations catch the stringent Patrik off-guard—”I don’t put any stock in metaphors, they’re too spongy for me. I prefer to rely on numbers and letters for orientation.”—it is eventually only in Leo-Eric’s company that Patrik is able to take true stock of poetry’s disembodiment as Celan had known it: that language, leaving the poet’s physical form, traverses the entire world in its immateriality, drawing new openings for itself by way of correspondence. Poetry as a liberatory method. Poetry as a direction.

In Celan’s verses, these passages can be paradoxically found in a sort of enclosure, through the poet’s radical and enduring application of portmanteau. In his verses one finds the thousandword, the saltflood, the heartbright, the ravenswan—and in the removal of that all-important space, one finds a methodology by which to navigate the motions of Tawada’s vertiginous, musical novel. What Celan perhaps knew better than most was the effect of the collision, the sheer power of separations as they are nullified, when words are relieved of their role as links, as elements of sense-making, and are instead reborn as ornate figures of their own logic. The white space in language operates as a demarcation, a distinctive marker of an end and a beginning, and through its erasure, one can conceive of language’s layer-effect, its prismatic capacities, not as single notes but as chords, just as how a migrant must simultaneously fit multiple continents into her single mental landscape.

As Tawada erratically steers the inner monologue of her narrator across “dead words” and “fresh-squeezed words”, across the incohesion of a physical body holding an everywhere mind, across a haunted sense of loneliness, she allows the prose to flow in polyphony, much like a fugue and its intensive overlap. Celan’s poetry—which acts as fulcrum, enigma, point of desire for Patrik’s itinerant meditations—is thereby turned into a kind of legend for the crises and anxieties of our contemporaneity: ubiquitous surveillance, racialized systems of securitization targeted at refugees, the deployment of phosphorus grenades in Iraq, the horrors of Israel’s continuing genocidal violence in Palestine, the last of which Leo-Eric, whose grandfather “stayed glued to his radio . . . when he heard about the Israeli air force striking Egyptian military bases without warning.”

Here, a more potentially explosive aftermath of trans-cultural reading is momentarily opened. Tawada hints at how someone from another side might interpret the work of Celan, but does not fully tease out its implications. Celan, after all, wrote to Yehuda Amichai, “I cannot imagine the world without Israel, and I will not imagine it without Israel.” It is a consideration, however brief, that forces readers to contemplate the unforeseen reverberations of a meridian that purports to pass through all things. To what degree might Celan’s undressings of suffering, cruelty, and displacement move through the works and minds of non-Jewish peoples, and those who have suffered directly from Zionist settler-colonial violence?

When writing about her own trans-cultural encounters in the essay collection Talisman, Tawada posited her own ardent resistance to the use of narrative representation in deciphering other realities. Assuming a momentary suspension of meaning, she mobilized a Barthesian method of reading the spaces and things around her as text, as opposed to any straight-forward attempt at cross-cultural exchange. Ultimately, in her view, everything can be folded back into the architecture of our own considerations, into the archives of Selfhood. In Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel, the procession of current affairs, alluded to in throwaway lines, only ever feels like a screen on which Patrik’s literary yearnings can be projected, and for all the mutuality splicing through the novel, Tawada always returns to the underlying theme of the self, and therein locates the real strangeness of unity. In the interface between page and mind, is it the reader or the text that is transformed?

For this, Bach has an answer. The master of contrapuntal composition knew that when listeners loved a melody, what they were really loving was the harmony; a true collaboration results in the illusion of singularity. This musical theory informs how Tawada apportions a thinking mind as the singer, and the world as a symphony, by way of ever-shifting mutualities, equilibriums, interpretations—with the great conductor of Time being the sole force keeping everything in tempo. For those of us reading in English, this conflux is extended even further by the meticulous, vivid translation of Susan Bernofsky. Working in concert with Pierre Joris’s renowned translations of Celan, Bernofsky layers yet another strain into the score. In this, the coalescence of Celan, Tawada, Bernofsky, and Joris resonates with a sentiment made by Theodor Adorno while praising Celan in a letter: “. . . I had the impression that an element of music had fallen into poetry, like it had never happened before, in a way that has absolutely nothing to do with the cliches. . . .”

And so does Patrik and Leo-Eric’s conversation, through its synchronicities and parryings, begin to take the shape of an opera. An earnest tenor rounds off the baritone’s overture; one soul thrills to another’s music, and all through the voice—that most naked of signatures, whose fugitive address manifests in carrying the impersonal medium we know as language. Paying tribute to her chosen literary ancestors even as she swerves away from them, Tawada’s music-prose is a testament to the spirit of collaboration: to the miracle of being able to test, with and against another consciousness, how far a language might pass from one private recess to another.

Xiao Yue Shan is a writer, editor, and translator. shellyshan.com.

Alex Tan frequently writes for Asymptote. https://linktr.ee/alif.ta.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: