In contemporary Indonesian literature, the writer Afrizal Malna has earned his own movement. Coined by Universitas Gadjah Mada professor Faruk HT, the Afrizalian has come to mean “seemingly disjointed images and ideas wrapped inside deceivingly simple phrases,” according to University of Auckland’s Zita Reyninta Sari, who goes on to elaborate the ways that it puts “everyday objects, especially those which in a glance are the most mundane … in the spotlight.” In his foreword to Afrizal’s Anxiety Myths, translator Andy Fuller also contributes to the definition: “An Afrizalian aesthetic is an engagement with the physicality of the city. How the body collides and rubs up against the textures of the city; of the varying intense urban spaces of everyday life.”

A SEA Write award-winning writer and artist sketched as “one of Indonesia’s best contemporary poets,” Afrizal’s works have been translated from their original Indonesian into languages such as Dutch, Japanese, German, Portuguese, and English, and have received accolades from literary award-giving bodies in Indonesia and beyond. To name one, Daniel Owen’s translation of Afrizal’s poems was the winner of Asymptote’s 2019 Close Approximations Prize.

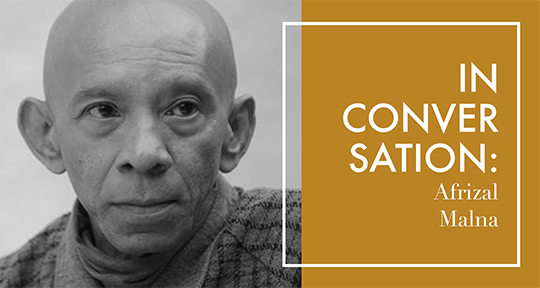

In this interview, I spoke with Afrizal—currently in Sidoarjo in East Java—with the help of Owen’s translation. Our discussion covers the Afrizalian literary movement within contemporary Indonesian poetry and drama; the terrains of linguistic hierarchies and reader reception; and his latest poetry collection Document Shredding Museum, originally published as Museum Penghancur Dokumen in 2013.

Alton Melvar M Dapanas (AMMD): Your latest collection, Document Shredding Museum, is now out from World Poetry Books. Could you tell us about the collection’s journey?

Afrizal Malna (AM): This edition of Document Shredding Museum is actually a revised, second edition of the book; the first edition was published by the Australia-based publisher Reading Sideways Press in 2019. In Indonesia, it was published a decade ago. The answer I’m giving you to this question now is probably quite different from how I would have responded back then.

This book was written between 2009 and 2013, over a decade after the fall of the Suharto regime and the 1998 Reformasi. This regime ruled from 1966 to 1998 as a result of the 1965 tragedy—the massacre of members of the Indonesia Communist Party (Partai Komunis Indonesia or PKI) and those accused of being Communists, alongside the overthrow of the prior president Soekarno—which is still full of question marks even now. 2009 to 2013 was a time when the Indonesian people began questioning: what resulted from the 1998 Reformasi? Has there really been a fundamental change? We wondered if the powerful in Indonesia will always be prone to nepotism and its corollary effects—such as legal, ethical, and human rights violations, as well as corruption.

It was also during this time that I lived in Yogyakarta, in a Javanese cultural environment, occupying the boundary between village and city as a blurred space in Nitiprayan, Bantul (still a part of Yogyakarta). This became the moment for me to start from zero, and to allow my activities to mimic the wind, moving to find empty spaces and lowlands. This blank slate could shift the past—which was filled with hope for political change, as well as hope for literature and art to respond the 1998 Reformasi.

Global society at that time was facing social upheaval and natural disasters. When the earthquake in Padang, West Sumatra happened, I was living in a house that I had rented from a family of farmers—an old, fragile Javanese house (rumah limasan) made of wood. The earthquake made the house convulse, and it was as if the house were dancing along to the earthquake’s rhythm in order to avoid collapse. When the earthquake stopped, not a single part was damaged, but many of the houses made of stone or cement had cracked or collapsed. It felt as if the wind had vanished. Leaves were stiff like in a painting, and the feeling of solitude, of quiet, was stifling.

That natural disaster, among many others, reflected the awareness that our bodies and our technology were paralyzed, powerless. Our ancestors, who had a long history of facing disasters, may have known how to read the portents of an upcoming disaster as an ancient form of mitigation, but this knowledge was not passed down to us.

These events gave rise to an obsession, or an agitation: “Can language shake? Can meaning convulse?” It was a new challenge for the practice of writing poetry. For example, there is one poem whose title is directly connected with the eruption of Mt. Merapi:

Merapi vomits Jakarta. This is green lava. This

is brown lava. Straight as the ruler measuring

your calf. Please, choose to be photographed. Please, take a photo.

Please, take a photo. Gentlemen, there’s a hot cloud in the way

you drive your cars. Looking

for donations. Fashioning heroes out of

volunteers. Fashioning the people as victims

and refugees. Thousands of speakers gather among

microphone cables heading for electricity. The gentlemen don’t

know the meaning of chicken and cow. Merapi

vomits Jakarta, a very straight color.

A very straight grid measures the lava. The gentlemen

of parliament are on break in Germany, using up

their year-end budgets. The ladies are busy

with the national income and expense

budget for the coming year.

For me, the structure of the poem and the way the words are placed resemble an earthquake with its propensity to convulse, which perhaps can shake up the balance in reading. Jakarta is positioned as a city of politics and economics, in accordance with its status as the capital.

AMMD: How different is Document Shredding Museum from your other collections previously translated into English like Morning Slanting to the Right (tr. Jorgen Doyle, Hannah Elkin, & Andy Fuller) and Anxiety Myths (tr. Andy Fuller)—in terms of your creative process and poetic underpinnings?

AM: I live only in Indonesian, a language stemming from a national policy to unify the hundreds of local languages in Indonesia. This reality has accustomed me to living within various languages I don’t understand. I’m accustomed to being part of the majority in certain situations, and part of the minority in others, because of the language I use.

When I encounter my works translated into a foreign language, I am once again thrown into a foreign atmosphere. It is no longer my work, having moved into a different world, so I never know the results of the translation. When I discuss the differences between Document Shredding Museum and the other two books you’ve brought up, my response pertains to the books in the Indonesian-language imagination.

Anxiety Myths is a collection in which I began to draw a boundary between language and the body as the first layer of writing. When we take language as the first layer of writing, we must remain constantly aware that language is a representation machine through which immense distortions take place, positioning us within language as the past. This awareness caused me to try to see the body as the first layer when writing; I refer to it as a “body-that-writes” (“tubuh-yang-menulis”). This positioning not only brought my sensory experience to the poems, but also allowed traumatic experiences to become part of the writing. The body works like an algorithm that indexes experiences as image, sound, scent, texture, and spatial landscape. This process made things or objects more provocative than words. It shifted the activity ratio from the instrument of language to the instrument of objects, and resituated the thinking process as an effort to make sense of images.

Each of our bodies is shaped by different histories and cultures. My books before Document Shredding Museum were published in the shadow of the Suharto regime, which used a culture of violence to lead Indonesia into a militaristic culture of silence. History was obscured.

Suharto’s presidency was actualized through the violence of the 1965 tragedy. The 1974 Malari Incident, a student demonstration against Japanese investment in Indonesia, was effected through this culture of violence as well. The 1998 Reformasi movement to topple Suharto was also accompanied by violence towards Peranakan Chinese Indonesians. Activists were shot or kidnapped and disappeared, including the poet Wiji Thukul, whose poems were often used in the Reformasi movement. Even now, the government still hasn’t taken historical responsibility for the disappearance of Wiji Thukul. I participated in both the Malari Incident and Reformasi with an overwhelming sense of fear.

These experiences, coupled with daily domestic practices, brought me to an awareness of the body as, on one hand, a terminal for memories and traumatic experiences, and, on the other hand, a signal reaching out to dreams and unseen other worlds. Javanese culture, along with many of the subcultures of Indonesia, is deeply rooted in animism in its spiritual cosmology, presence of a spirit realm, and mysticism.

In writing poetry, I experience this body-that-writes as a mutant in language; I feel a different person is present in myself. “What is the body, what is language, what is I?”—these questions arrive like falling rocks of incongruous volume and weight, rubbing against each other and falling together with the sound they produce.

In the process of writing, perhaps there is a “taming” of time. The Indonesian language doesn’t have grammatical tenses to divide time; time is a designation (lexical), rather than a linguistic projection (grammatical). This dimension of Indonesian therefore gives me the opportunity to conduct an exploration of time as a play of gaps, leaps, reversals, and fractures. When this work moves into English, I imagine a very interesting change in the dimension of time must occur.

Meanwhile, in Document Shredding Museum, a different layer began to sneak in. I wrote some of those poems using graphic design tools, and was also beginning to make videos based on my poems. In the years of 2009 to 2013, a lot was happening with the Internet, the computer, and cellular technology. We were just entering the era of digital currency, Android with its 3G speed, the era of social media playing revolutionary roles. Also, a great many archival sites were opened to free digital access, and we were suddenly flooded with new information.

In the middle of this flood there were many hoaxes as well—criminal currents meant to confound the ways we understand the Indonesian historical record. Indonesia’s independence in 1945 took place in the acute friction between nationalism, religion, and Communism. This tension was later disciplined by Suharto, primarily through the Tragedy of 1965, which entailed the massacre of Communists and those considered left-wing or infidel. Around this time, a number of Hindu historical sites were destroyed by religious fundamentalist groups, particularly in Java. Is it our right to destroy the culture produced by the generations before us? We’re trapped in a representational conflict, “a struggle over God,” through a religious perspective that claims absolute truth. And this was all happening in the midst of the technological developments with their post-truth discourse.

The internet demolished the identity of an “I” as a sole, individual position that proceeds continuously. Through social media, I experience commercialization as a multiple-I, or as data, or as an “I” that is multiplied as a series of statuses that we post. “I” here is a product constantly recycling between itself and I-which-is-another in social media space. “I” as a “dead ‘I’ pandemic” which we collectively celebrate through social media. This is the effect of what Richard Shusterman has called “informational culture” on private space, and this technological layer created a fog between the body and language in my poems. This is what makes Document Shredding Museum seem simpler, but with a more complex structure. The primary index of the book can be found in a phrase from its eponymous poem:

Document shredding machine

alone in your sagas.

The other book, Morning Slanting to the Right, is a compilation of my short stories, most being recordings of specific experiences that I wanted to share. One example is “xezok ker lubig job kurleksok,” which takes its inspiration from Andy Fuller’s visit to my apartment in Berlin. At that time (2014 to 2015), I was participating in the DAAD Berlin residency program, and Andy had come with his wife, Nuraini Juliastuti, and their child, Cahaya. Cahaya was still little and couldn’t yet speak. She was using a language she had made up herself. This moment was important to me, because I was meeting a figure who hadn’t yet been formed by language, and I could see the difference between the actions of a body that had been disciplined and ordered by language and that of one who was still untouched by language. This collection is like the narrative side of the world of poetry where I’ve built a spiderweb trap between the body, language, and reality.

AMMD: I am interested about your view on readership and reception—in particular among Anglophone and Westerner scholars. In “Poetry and an Epidemic of History: A Letter from the Author to the Translator,” you debunked certain claims on your poetry’s esotericism and disconnectedness. Could you speak more about it?

AM: Unfortunately I can’t read responses to my poems written by scholars working in English, but I would like to discuss the differences between readers in Indonesia and readers from European-language backgrounds in their understanding of my poetry.

For the most part, people of my generation, born around the end of the 1950s, haven’t understood my poems. However, there were some among the philosophy students at Sekolah Tinggi Filsafat Driyarkara (Jakarta) who published my first book of poems, Abad Yang Berlari, and a theater group in Jakarta, Teater Sae, who’ve performed many of my texts. I actually think that more people of the present generation can understand my poems, compared to people of my own generation.

Indonesian readers always need meaning. They see poetry as a product of language, and because of that, it has to be understood in accordance with the language used. However, in my poems, perhaps I have overthrown language in a coup d’état, so the poems can be seen more as artworks that use the element of words. However, European-language readers haven’t had a problem with meaning. For me, poetry isn’t directly connected to meaning as a destination, because meaning lies with the reader. The opposite is the case with short stories, where meaning is inside the story itself. The deficiency of the ways that poetry is taught in school contributes to forming a narrow literary culture for Indonesian readers. This is why poetry readings and performances are so important in Indonesia; they provide an opportunity for bridging this gap. Through poetry readings, readers can meet poets and talk with them directly.

When readers encounter my poems, especially in Indonesia, there usually is a sense of strangeness because I use that strangeness as a distancing mechanism for readers to perceive the boundaries between language and meaning—where the process of reading is equivalent to the process of opening a sort of “conceptual horizon.” Isn’t all art, including the cave paintings made by our ancestors, an effort to open such conceptual horizons?

AMMD: In Secrets Need Words, a book which surveyed Indonesian poetry from 1966 to 1998, you were imaged as someone who “remained a symbolist but . . . used the material images of the city, instead of rural landscapes of night, rivers, and trees.” In Writing and Rewriting National Theatre Histories, your work as a theatre scholar has been set out as a usage of post-structuralist models within theatre historiography. Would you say this is how the Afrizalian manifests in both poetry and drama: symbolist, metropolitan, and post-structuralist?

AM: Those terms that are applied to my work come from outside: post-structuralist, afrizalian, and then others call it “neo-materialist.” We’re living in what Richard Shusterman once called “informational culture”: a culture where experience, the body, and language have become past forms in the development of information technology. We’re flooded with information in the form of shattered space and time. To choose, arrange, shape, and manipulate through works of art doesn’t mean that we can overcome the spaces and time that have shattered. Here, structure becomes a new dynamic, like editing film or video to make a narrative that isn’t merely arranged in order, but also moves.

This shattered space and time is ever more pronounced in Jakarta, as a city formed by colonialism, a city that sought a new identity amidst nationalism, the capital city of the Indonesian state, and as a global city. It’s a city with severe social inequality between wealth and poverty—forced evictions of slums, street vendors, and pedicab drivers. A city convulsed by change and bewildered as to where to place its past. A city that actually celebrates the local war that destroyed the prior residents of the city—when it was still called Sunda Kalapa. (Afterwards it was renamed Jayakarta, and then Batavia throughout the colonial period, becoming Jakarta after Indonesia’s independence). This sort of urban culture forms the creative ecosystem for my work.

At first I was taken aback by the existence of the term afrizalian. What sort of creature is this? After that I tried to understand how this term was an effect of the literary politics that sought to marginalize anomalous forms of literature (like my work) as incomprehensible writings. The regime of lyricism has strong roots in Indonesian poetry, even now. Its roots are in Malay culture, because the Indonesian language is rooted in the Malay language. These roots are celebrated through the pantun tradition. In modern Indonesian poetry, lyricism was fortified through such poets as Amir Hamzah, Sitor Situmorang, Chairil Anwar, Goenawan Mohammad, and Sutardji Calzoum Bachri.

As for my relationship with theatre, it was initially formed through my participating in the social life of the Taman Ismail Marzuki Jakarta Arts Center. The Jakarta Arts Council, which runs various arts and literature programs, is housed in this arts center, and it connects many Indonesian artists through its programs. Through the social life around the arts center, I became close friends with a theatre director named Boedi S. Otong—the director of Teater Sae. We began a collaboration in which I worked as the text writer for their performances. You can see two Teater Sae performances that were recorded on video here and here. These days, Boedi S. Otong lives in Switzerland and hates theatre.

When I was writing performance texts, I didn’t try to learn more about playscripts; I thought I was just making texts to be performed. And, for the most part, I made those texts while watching Teater Sae’s rehearsals. In those texts, I brought in a lot of other texts. They became texts inside texts. Maybe now I’d call it a “text network dramaturgy.” This term is more appropriate for my practice than the term “post-structuralist.” In the middle of a performance of “Biography of Yanti After 12 Minutes,” for instance, there could be an interview in Indonesian that was translated into German, which may have seemed controversial in its time because of the intertexual practice.

I don’t know if my works have the symbolist qualities that Harry Aveling attributed to them; I have never consciously made symbols or utilized symbolist qualities in my work. What I know is that I have often worked with metaphors to bind space and time, and to wreck the law of linguistic linearity in the making of sentences. The grammar of the Indonesian language—which has its particular way of using affixes to change a word into a verb, an adjective, or a noun—makes it possible to transform grammatical play into lexical play.

AMMD: You have been translated by several translators across Dutch, English, German, Japanese, Portuguese—the languages of Indonesia’s colonizers. The very language you write in, Indonesian, is also a colonizing one towards the minoritized such as Papuan languages. As a writer and scholar working in a language that is both colonized and colonizing, how do you navigate linguistic hierarchies?

AM: This is a part of the tension in the identity politics of Indonesia’s history, which is directly related to how official policy has insisted on Indonesian as the sole national language.

My relationship with Indonesian is very dynamic. The character of Indonesian as a medium for writing is different from that of Indonesian as a medium for speech. As a medium for speech, all of the aspects of local culture can contribute to shaping Indonesian, but when it is written, it’s as if the language enters into a disciplined, orderly box. Every writer has the chance to disassemble the boundaries between these two mediums. One example of this is Linus Suryadi AG’s “Javanization” of Indonesian in his 1981 work Pariyem’s Confession. Another is Darmanto Jatman’s poems.

It seems that practices of this sort don’t make much of a meaningful impact. Education in the Indonesian language, which is massive in the schools, has pushed the present generation increasingly further from their mother tongues. Local languages are more alive in domestic spaces.

I’m part of a generation that doesn’t live in its mother tongue. I was raised in Indonesian, though my parents came from the Minangkabau culture in West Sumatra. When I participated at Performance Platform Lublin, I spoke in Indonesian, and Melati Suryodarmo translated. Waldemar Tatarczu, the curator of the program, listened to my speech, and commented that many of the words I used are present in European languages: Portuguese, Dutch, English. Of course. Indonesian has lost its Malay roots, and Malay culture itself has undergone a long process of Islamization. Indonesian, like the country of Indonesia itself, has been shaped by numerous nations; China, India, Arabia, Portugal, Holland, and England have all contributed.

I myself wonder why other local languages haven’t been made national languages. It’s a complex question, because Indonesia has around seven hundred local languages, and many of them in Papua. Why hasn’t Javanese, the language of the majority in Indonesia, been made into a national language? The lexicon of Javanese is far more numerous than Indonesian, and also far more complex because of its integration with the complex Javanese culture.

In the future, the presence of Indonesian will increasingly threaten the presence of local languages. What’s needed is language education that teaches Indonesian through the local language of each area. That could become a bridge for overcoming an Indonesian language that doesn’t represent the sea-based culture of Bugis language speakers, or the Hindu culture of Balinese language speakers, or the forest-based culture of Dayak language speakers, and especially for the agrarian culture of Indonesia’s great many farming communities. And, conversely, the Indonesian language will be threatened in the future by the growing numbers of English language speakers. Perhaps there is a presumption that it isn’t possible to be a part of global society if one lives using only Indonesian.

AMMD: Among the books you’ve written that have not been translated into English yet, which one do you think would be the most difficult to translate? And what demands would a translator face?

AM: I think Document Shredding Museum is the most difficult of my books to translate. Some of the poems feel too global, some too local. And most of them exist loosely from their context or background. They exist like images that have been cropped and their backgrounds discarded. I don’t know, do readers still need the context of temporal and spatial background in reading Indonesian-language poetry?

I can’t imagine what kinds of difficulties emerge in translating my works. I imagine language as a stage for works of literature written by whomever, and the design of that stage depends quite a bit on the insight and courage of the translator. I imagine translating a work of literature might be far more difficult than writing one. The presence of machine translation actually reinforces the notion that every translation practice is also a work of cross-cultural encounter, because machines can’t yet enter into the world of language as a culture-forming space.

Maybe at first translators are frustrated by my poems, and then they get drawn in, agitated, as they go deeper into them (as if they feel that they themselves are making them). And then they come out again to take some distance, to make a strategy and a design, considering the various possibilities that can occur in the cultural encounter between the first language and the second language as a product of translation.

AMMD: When we speak of Indonesian Literatures, who has shaped your philosophy, your creative-critical writings, and your ethos?

AM: When I lived in Jakarta, my house wasn’t too far from the H.B. Jassin Literary Documentation Center, the largest library of Indonesian literature in the city. Through this library, I read a lot—including private letters between authors. For some time I allowed myself to drown in Indonesian literature, and I began to build a personal library. Later on I came out of that, using my body to read the reality that I experienced. I even left behind the personal library I had built. Then I became involved with the urban poor movement in Jakarta through the NGO Urban Poor Consortium. On several occasions, I was arrested by state security forces for participating in this movement.

Indonesian literature is a literature whose primary canon was mapped by H.B. Jassin, A. Teeuw, and later Umar Junus. With the 1965 Tragedy, many works by authors associated with the Indonesian Communist Party were burnt—and of course they didn’t enter into this mapping. For myself, an understanding of what constitutes Indonesian literature is incomplete, due to ideological problems and the sharp split between modern and traditional literature. This has caused Indonesian literature to depend solely on texts written in Indonesian, while the ones in other local languages remain unmapped. So the situation is complex.

Through these points, I want to express that I am open to influences from many factors, because every influence presents new challenges and contributes to repositioning my perspective on writing. And because of this I can’t say who has had the most influence on the ways I write poetry.

I have been greatly intrigued by Ludwig Wittgenstein’s notion of language games, which I’ve read about through essays written by Indonesian writers. But Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations hasn’t yet been translated into Indonesian. This has caused my understanding of language games to be rather vague. My understanding of Walter Benjamin’s concept of aura—as a perception that reverberates when we look at a work of art—is likewise vague.

I think I must be very sensitive to influence. Every time that the rain and wind arrive, it rattles me. An influence then becomes a kind of laboratory for opening things up, and then it’s as if I’ve received a new path for writing. This makes it hard for me to identify a particular poem or a particular poet that has influenced me directly. The trace has already vanished. I’m happier with saying, for instance, that my poetry is written by many poets.

AMMD: Are there contemporary Indonesian poets and playwrights whom you wish to be read more (or in the case of playwrights, their works be staged and performed more) globally or even translated further?

AM: I enjoy the works of contemporary Indonesian poets such as Ratri Ninditya’s Rusunothing and Gratiagusti Chananya Rompas’ e____y. Both of these poets mix Indonesian and English in their poems, using diction unique to the youth of Jakarta. Rompas doesn’t call her books poetry collections anymore, but “writing collections.” Another poet whose work I want to mention is Oz Valkyrie, who wrote Selibat.

Or the work of Rachmat Hidayat Mustamin—Indeks Penghabisan Manusia. This work is a collaboration between poetry and graphic design. Each poem is imagined as being read through a handphone—one scrolls to get to each page—and all of the poems are untitled. Rachmat mashes up data in his poems as well, for instance data about domestic violence with data sourced from religious practices.

The work of these four poets doesn’t just manifest poetry, but also creates a new disturbance of what poetry is. It seems to me that there are a number of poets who work not based on the conventions of poetry, but based on the new challenges they face as a result of changes in their environment.

AMMD: If you were to teach a course on Indonesian Poetry, what poetry collections and poems (in Indonesian languages or in translation) would you wish to include as key texts?

AM: In the poetry classes I’ve taught, I’ve never used any poems as material. I try to challenge participants to use basic things—for instance, moving the cup of coffee on the table into words. When the movement is complete, I put forward another question: what is lost in this movement? How do we respond to what has been lost—what we see after the object has been rewritten through the medium of words?

After this, I ask the participants to move the words once again, from Indonesian into their respective local language. And then I put forward a new provocation: what has changed through this movement?

Other materials that I’ve used are more based in visual arts. For instance, using the work of Marcel Duchamp to discuss the limits of what’s art and what’s not art; using the work of Joseph Kosuth to discuss the practices of representation, presentation, and performativity in creating a work; using the work of Rene Magritte to discuss the practice of forming metaphors; works of performance art, like Carolee Schneemann’s performance “Interior Scroll,” to discuss the relationship between text and the body; or the poems of Mirtha Dermisache, which can’t be read.

There are two books of mine that I think are interesting for sharing poetry writing methods. The first is Berlin Proposal, which was made very intensely while I was participating in DAAD Berlin. At that time, Berlin was celebrating the centennial of World War I, and I began tracing data about the war as the basis for creating poems. I also encountered a number of curatorial practices that were quite diverse in visual art, literature, film, theater, dance, and at the big museums in Berlin—an experience that opened new perceptions for me and connected art and history. In this book, I started to make data present as poetry. I was very pleased when Daniel Owen gifted me a book of poetry by Carlos Soto Román, 11. This work takes its title from events of September 11, 1973, when Augusto Pinochet overthrew Salvador Allende as President of Chile. In Soto Román’s poems, classified state documents, in the form of letters, are made present as poetry. This book gave me a new companion in the practice of connecting poetry to archives or data.

The second book is Prometheus Pinball, which uses a method of expanding my biography through global history. I used this method to make history into biography, and conversely to expand the territory of biography as an expansion of identity. My position in poetry became my position in history, which is inhabited by many people. Andy Fuller, who published this book, once made the comment that it isn’t poetry. I was happy to hear Andy’s opinion, because it gave rise to discussion about the ways we perceive poetry in the midst of the information revolution, brought about by internet technology.

Other materials that I might use are traditional sources that aren’t easy to access. I use them to read the past and bring it into the present, and this journey back and forth causes one to wonder what sort of bridge can be made to span the great distance of time between us and traditional sources. How poetry has a special way of acting as a medium for the construction of time bridges.

This interview has been translated from the Indonesian by Daniel Owen.

Afrizal Malna, born in Jakarta in 1957, is an Indonesian poet, artist, and writer of short stories, novels, essays, and playscripts. His work has won a number of national and international literary awards including SEA Write Award and the Khatulistiwa Literary Award. He was a 2015 DAAD artist-in-residence in Berlin and has performed at poetry festivals in Bali, Bremen, Maastricht, Hamburg, Kerala, and Yokohama. He has been translated into Dutch, English, German, Japanese, and Portuguese. Other books of his in translation are Morning Slanting to the Right and Anxiety Myths. Among his earlier books include Abad yang Berlari (1984), Yang Berdiam dalam Mikropon (1990), and Arsitektur Hujan (1995). His works also appeared in Indonesian anthologies such as Perdebatan Sastra Kontekstual (ed. Ariel Heryanto, 1986), Tonggak Puisi Indonesia Modern 4 (ed. Linus Suryadi, 1987), and Traum der Freiheit Indonesien 50 jahre nach der Unabhangigkeit (eds. Hendra Pasuhuk & Edith Koesoemawiria, 1995). He also edited Radio ½ Radio: Antalogi Naskah Drama Dan Analisis Dramaturgi (2019) and Tiang Hitam Belukar Malam (1996). For the theatre group Teater Sae, he has written plays and performance pieces such as Ekstase Kematian Orang-orang (1984), Pertumbuhan di Atas Meja Makan (1991), Biografi Yanti Setelah 12 Menit (1992), and Migrasi dari Ruang Tamu (1993).

Alton Melvar M Dapanas (they/them), Asymptote’s editor-at-large for the Philippines, is the author of M of the Southern Downpours (Australia: forthcoming), In the Name of the Body: Lyric Essays (Canada: Wrong Publishing, 2023), and Towards a Theory on City Boys: Prose Poems (UK: Newcomer Press, 2021). Their works—published from South Africa to Japan, France to Singapore, and translated into Chinese and Swedish—appeared in World Literature Today, BBC Radio 4, Oxford Anthology of Translation, Sant Jordi USA Festival of Books, and the anthologies Infinite Constellations (University of Alabama Press) and He, She, They, Us: Queer Poems (Macmillan UK). Formerly with Creative Nonfiction magazine, they’ve been nominated to The Best Literary Translations and twice to the Pushcart Prize. Find more at https://linktr.ee/samdapanas.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: