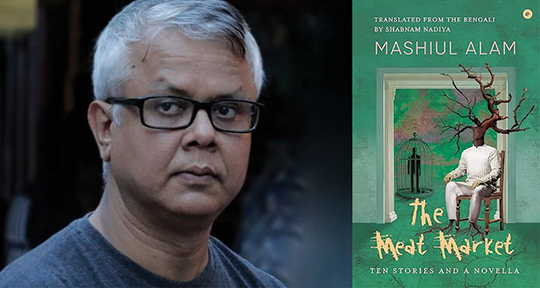

The Meat Market by Mashiul Alam, translated from the Bengali by Shabnam Nadiya, Eka Westland, 2024

From its first story, The Meat Market amply indicates the weirdness that awaits readers. Written by Mashiul Alam, who was born and brought up in northern Bangladesh, this collection brings together short fiction originally written in Bengali, translated into English by Shabnam Nadiya, who continues to prove her skill. Described as “surrealist political horror,” the politics of The Meat Market is not an extraneous element limited to politicians and statecraft, but an omnipresent, embodied aspect of people’s lives; there is not a single sphere, no matter how small, devoid of it. Alam makes full use of affective disgust to drive this point home, letting the macabre and the absurd rise as the defining forces, thereby showcasing the hypocrisies of Bangladeshi society and the daily realities of the citizenry. These stories challenge social mores and underline existing fault lines, hidden behind the veneer of normalcy.

Perhaps the most chilling work in this collection is “Field Report from Roop Nagar,” which is written from the first-person perspective of an editor at a daily newspaper. As a regular work day passes, he slowly discovers that he is unable to get in touch with anyone who lives in Roop Nagar. He tries friends, colleagues, relatives—but the call either does not connect or just keeps on ringing, no one ever picking up. He asks people who live near the area to go and ascertain the situation, but they too become unreachable. Soon, the general public and the government also catch up to the fact that there is no way to connect to Roop Nagar. Only one piece of evidence is revealed: supposed field notes from one of the narrator’s eccentric colleagues, consisting of a video clip and some audio recordings. Together, they relate, in graphic detail, the horrific murder of a girl.

Based on the report, she had been abducted in broad daylight by a group of boys for having a “bad character,” while everyone watched and did nothing to save her: “She pretended to be in love and ruined the lives of many boys. They picked her up to punish her.” Her throat was slit, she was dismembered, and afterwards, the boys cooked her remains and consumed her. They could not stop eating, and upon finishing all the meat, they fell into a deep slumber. As they slept, the other townspeople began to fall asleep as well, going unconscious in a widening circle. Everything came to a standstill. Anyone from the outside who tried to enter met the same fate. It is a metaphor made real—those who were unseeing, whose eyes had turned away from the girl without a sound, had gone unconscious in actuality.

It is a theme that repeats in the titular story (first published in Asymptote’s Winter 2019 issue), which follows closely in the horror factor—again serving to show how so-called model citizens sleepwalk through life, ignoring atrocities happening right in front of them, so long as they are unaffected. In the story, Aminul Islam is roused from sleep by his wife and tasked with the chore of buying meat—which involves making sure that it is pure khashi, a he-goat, and not adulterated with sheep or she-goats. When he arrives at the market, the butcher and his assistants are slaughtering all animals together, brazenly mixing the meat in an indiscriminate heap right out in the open. When Aminul Islam protests and demands pure khashi meat, they butcher him as well, while the other customers watch on. Soon, his flesh is also mixed into that pile and sold. Detached from his body and with mounting horror, he describes his murder and how his flesh is integrated into the meat bought later by his brother-in-law, which goes on to be delightfully consumed by the rest of his family.

All of the stories in The Meat Market have political undertones, even if only through passing remarks on its sustained background of multivalent conflicts: religious or sectarian divides; the war of independence and its fracturing of well-knit communities; the crises of subcontinental identity; the concept of insider and outsider; and opposing opinions on what Bangladesh mean to its people. A perfect example of more direct political commentary would be “An Indian Citizen Came to Our Town,” which revolves around an old man, born in Bangladesh but living in India for the last fifty years, now returning to the motherland in the hour of his death. Old wounds of the Partition are reopened upon this visit, and hostilities are aired with a brutal but practised ease. A story like “The Underpass,” on the other hand, tilts more into absurdism; in an eerie exploration of the repressive state apparatus, three men corner the protagonist Kabirul, forcing him into going with them. Their walk goes through the city in all its idiosyncrasies, and he is finally taken to an underpass, where he witnesses extrajudicial killings being carried out, as monkeys give massages and pocket-sized constitutions are sold. A similar fatal fate awaits him at the end of this ordeal.

“Jamila” is another great example of Alam’s satire: a story in which the eponymous cow, named after her owner’s ex-wife, tries to graze in the parliament lawns in a fit of hunger. When she is stopped by the guards, she inadvertently gores one of them to death, which results in her being shot and arrested. Live TV debates, newspaper op-eds, statements from rights groups, and protests by the opposition all follow these events, while Jamila herself goes missing within the prison system.

Other stories take such absurdism into the realm of the surreal, usually with a magical realist underpinning. In “Milk”, when Julekha’s breasts dry up, her son takes to the teats of a she-dog who has recently lost all her pups. When his father finds out, he kills the dog in a fit of violence. That night, the people of Modhupur look on in astonishment as a flood of milk takes over the land—a “moonlit milk-sea” in which the son and the resurrected dog swim.

The collection closes with a novella that highlights Alam’s talents as a writer, but occasionally verges on tedium at its length of a hundred pages, indicating that the author’s strength lies in shorter fiction. “Pony Masud,” appropriately subtitled “An Account of the Tangled Stories and Gossip about him as Narrated by the People of Roop Nagar,” is a fascinating jumble of viewpoints. There is no focalised narrator but an amorphous ‘we,’ a third-person collective made up of all the residents of Roop Nagar. The novella is quite non-linear in chronology, frequently jumping across time to fill in anecdotes and backstories, going on in lengthy asides and commentary. Largely revolving around the infamous Pony Masud, once a small-time local gangster and now a politically well-connected criminal, the narrative is an exploration of his character as seen through the eyes of others, and early on, there is a self-conscious acceptance about the twisting and turning narration:

Stories and gossip about him exist mostly in Roop Nagar. However, the stories and gossip that the people of Roop Nagar share about him are almost impossible to present in a neat and tidy manner because all their stories are tangled up and knotted. They describe later events early, and earlier events later, they go off on tangents, skip from one topic to another, and then they lose track of all these topics and suddenly go back to their original topic, and then start telling the same story again in a new manner.

The story begins when Dhaka newspapers arrive in Roop Nagar, with headlines proclaiming that one Pony Majid has been arrested by the Rapid Action Battalion and subsequently killed in a ‘crossfire.’ The name causes confusion at first, but the residents simply assume that the newspapers have misprinted Masud as Majid. Thus begins a train of recollections starting from Masud’s childhood—his father who is a corrupt college principal; his mother and her affair with a brick kiln owner, who soon becomes Masud’s stepfather; other goons of Roop Nagar both living and dead; the notables of the neighbourhood. All of this is held against the backdrop of Bangladesh’s tumultuous political history, weaving a complex tapestry of this locality and its people, a ‘lived history’ that amplifies dailiness. “Pony Masud” gives an intense feeling of being at a quintessential adda, eavesdropping on the ongoing conversations.

Violence is the throughline of Mashiul Alam’s fiction; while it does not always spurt out in volcanic eruptions, it remains viscerally bubbling, right under the surface. Even if the story appears to have assumed a lackadaisical air, sudden turns of explicit violence or its palpable promise remains a continual possibility. The brutality of such acts is perhaps why, in multiple stories, ghosts remain alive enough to interact with still living characters; the past has certainly not lost its hold, nor the recriminations stemming from it.

The base level of human existence is poised on a knife’s edge, and it would be a disservice to reduce it to a malaise of postcoloniality—even though that plays a role. Shabnam Nadiya’s capable translation brings out these multi-dimensional aspects of Alam’s stories quite well, resulting in a collection that highlights the gruesomeness of reality in often shocking ways, from politics of the home to that of the nation-state. With such a potent combination of the incisive and the strange, one hopes that The Meat Market will be the first among many of Alam’s works to be introduced to the English-language world.

Areeb Ahmad is editor-at-large for India at Asymptote and books editor at Inklette Magazine. Most of his writing can be found on his bookstagram, a true labour of love. Their reviews and essays have appeared in Scroll, The Chakkar, The Federal, Hindustan Times, and elsewhere.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: