Lau Yee-Wa’s Tongueless was published before the 2019 pro-democracy protests that saw two million people take to the streets in Hong Kong, but its prescient atmosphere of psychological horror and brilliantly embedded language politics anticipated the curtailing of Hong Kong’s linguistic and social liberties after 2020. Demonstrating Lau’s percipience and sensitivity, Tongueless is a timely and vital addition to the growing corpus of Hongkongese literature available in English. Jennifer Feeley’s masterful translation follows in her track record of translating titles from Hong Kong—most recently Xi Xi’s Mourning a Breast (New York Review Books, 2024), for which she was awarded a 2019 National Endowment for the Arts.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

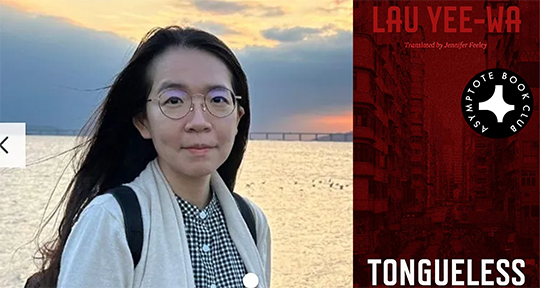

Tongueless by Lau Yee-Wa, translated from the Chinese by Jennifer Feeley, Feminist Press (US) and Serpent’s Tail (UK), 2024

Allegory depends on wordplay, and Tongueless starts with its title. The two ideographs in the original Chinese title, 《失語》, stand respectively for ‘loss’ and ‘language’. Together, they can both denote aphasia, a form of brain damage that hampers speech, as well as a Chinese expression that refers to a ‘slip of the tongue’. In Jennifer Feeley’s acerbic translation of this novel by Lau Yee-Wa 劉綺華—originally published in 2019 in what the copyright page calls ‘Complex Chinese’—《失語》becomes Tongueless. Lau’s psychological story of horror and loneliness in Hong Kong transfigures the metaphorical resonance of tonguelessness—losing one’s language, or mother-tongue—into a near-literal embodiment of mutilation and physical deprivation, a bloody allegory for the silencing and violence that Lau charts through the interpersonal and institutional politics of contemporary Hong Kong society.

In the lingual sense, Hong Kong is the complete opposite of a tongueless city; most of Hong Kong’s seven million inhabitants speak a locally inflected, essentially creolised form of Cantonese, with ample English code-switching that differentiates it from the Cantonese spoken across the mainland Chinese border. Contrary to the dominant language in mainland China, Cantonese is unintelligible with spoken Mandarin and not fully expressible in standard written Chinese. Feeley’s translator’s note, at the end of Tongueless, explains the history of this ‘unique linguistic landscape’ in insightful detail: ‘Whereas standard written Chinese ostensibly serves as a unifying written language, written Cantonese captures the specific nuances and expressions of the Cantonese spoken form.’ Despite this, the legal, educational, and majority of literary texts in Hong Kong utilise standard written Chinese grammar and characters—though spoken aloud using Cantonese pronunciation.

The immediate, brilliant complexity of Lau’s text lies in her code-switching between written Cantonese and standard written Chinese. Her Hongkongese characters ‘speak’ in Cantonese, while the Mandarin dialogue and the bulk of narrative prose is rendered in standard Chinese. For a reader of the ‘Complex Chinese’ Tongueless, Lau’s code-switching verbalises the cognitive dissonance inherent in the linguistic and sonic experience of everyday Hong Kong, something that most Hongkongers have internalised and take for granted. In a sense, Feeley’s version of Tongueless is a double translation out of and between two languages, an equally complex challenge. She renders these tonguefuls via an impressive rendering of United States versus Uniked Kingdom Englishes to stand for Cantonese and Mandarin: for instance, a mainland Chinese character who misspeaks Cantonese refers to ‘eggplant’ and ‘zucchini’ as ‘aubergine’ and ‘courgette’.

Another technique that Feeley employs to translate nonfluency is mispronunciation, a fertile ground for punning and allusivity. Wai, one of Tongueless’s protagonists and a native Cantonese speaker trying to learn Mandarin, is forced to chair the debate team, to which she says: ‘I don’t know how to say dupe-bait in Mandarin—’. Feeley’s eye for the pun, especially one with such apt connotations of trickery and distrust, evidences not only her skill in translating between various Chineses and English, but her deep understanding of Tongueless’s contemporary Hongkongese context.

The question of language and tongues is also one of national identity. As Tongueless was published in Hong Kong in the year of its major pro-democracy protests, these lines are drawn in the ‘loss’ 《失》, or the ‘-less’ suffix, of its title. Its central premise, hinged on the tangible tension of enforcing the Mandarin language in otherwise Cantonese-speaking schools, draws from real, recent worries about its possible implementation in Hong Kong’s public policy, and its consequences for the Cantonese language as a cipher of the Hongkongese identity. Along with Wai, our narrator Ling teaches standard written Chinese via Cantonese at a fictional school in Kowloon: Sing Din Secondary School (pronounced Shengdian in Mandarin). One of the literary texts that they teach is Xiaosi 小思’s Hong Kong Story《香港故事》, published in 2002 and recording the flavours and daily experiences of colonial Hong Kong. A student reacts: ‘In summary, Hong Kong’s origins are hazy, neither Chinese nor Western, but now it’s becoming clearer. Schools are all switching to teaching in Mandarin. This lesson is useless. I don’t want to study it.’

The ‘Hong Kong story’ has since been picked up by the Hong Kong government as a propagandistic hook, redolent with the notion of controlling the narrative, providing a single, smooth story of how Hong Kong fits into China. In comparison, Tongueless is another, more honest ‘Hong Kong story’, mirroring Hong Kong’s plurality and elucidating the darkening, authoritarian clarity of Hong Kong’s future. It enables questions of identity and nationality, belonging and discrimination, justice and tyranny, in a nation mired by censorship and the collective disappearance of its native tongue. Lau’s novel, then, charts Hong Kong’s descent into tonguelessness through the prism of its protagonists.

Just as it melds Cantonese and standard Chinese, Tongueless’s narrative skips between two timelines, present-day and flashback, interspersed with each other in Lau’s fluid storytelling. In the novel’s present, Ling is ostracised after Wai commits suicide after her first full year at Sing Din; while the other narrative line describes the year Ling and Wai spend as co-workers, a blurry relationship with more bullying than friendship, more terror than kindness: ‘What could be more exhilarating than monitoring Wai’s every move? What if Wai was a “wolf in sheep’s clothing,” secretly plotting with someone against [Ling]?’ Both are employed on a contractual basis, though Ling has been with the school for a decade; Wai is a junior teacher in her first year out of university, awkward and near-tongueless in her stuttering Mandarin: ‘If possible, I’d like to create a Mandarin-speaking en-fry—no, en-vi-ron-ment. This is the only way to speak as well as those whose mother tongue is Mandarin. . . . Not being able to speak Mandarin in Hong Kong is a duh-defiency, another kind of dis-dis-disability.’

Lau’s exposition sets us in the staff room the September after Wai’s passing, where much of Tongueless’s social intrigue and societal satire ensues: ‘the teachers’ office was like a sealed-off structure; no one mentioned Wai unless they absolutely had to.’ Caught in the switch to Mandarin, Sing Din’s Chinese teachers must pass scores of acronymised exams to renew their contracts. In this climate, both Ling and Wai are tongueless, at risk of unemployment, and literally unable to communicate. Ling takes Mandarin classes where the mainland Chinese teacher tells Ling to ‘forget [she’s] a Hongkonger’, and ‘just speak Mandarin, think in Mandarin, even dream in Mandarin if you can’. Three months after Wai’s death, with her desk still uncleared, Lau foregrounds these political intrigues in the symbolism of Wai’s belongings: ‘the pens in [Wai’s] pen holder were categorized by color […] resembling a national flag from a distance’, and ‘Wai’s desk and bookcase were covered in mirrors—a small round convex surveillance mirror . . . on and on, all of them connected like one mirrored sea.’

Lau’s attention to ominous, oppressive details pervades Tongueless, hitting all the marks of your typical psychological thriller: an unreliable narrator, swerving mind games, and an atmosphere of suspense and doom. The characters often ‘spit out’ their lines, as though physically tongueless. But Tongueless’s engagement with Hong Kong’s sociopolitical reality and the matrix within which Wai and Ling undertake their separate fates (‘absolutely spine-chilling, bloodier than a family massacre’) distinguishes the novel from other thrillers in its critique of an absurd horror: Hong Kong’s bureaucratic apathy and systematic repression. Throughout, she rehearses Hongkongese stereotypes of consumerism and self-centeredness in order to parody them: ‘Hong Kong people really lack imagination,’ a secondary character asserts. ‘Hong Kong people . . . only care about making money. . . .’

Ling’s retail addiction is another, unspoken form of tonguelessness: ‘As soon as [Ling] arrived at IFC Mall, she ran up the long escalator, making a beeline for Céline and Valentino. . . . In one evening, she spent a whopping 60,000 HKD’ (equivalent to about 7700 USD in December 2019). For Ling, undoubtedly traumatised by Wai’s suicide and Sing Din’s attempted cover-up, Wai’s life and death are the objects of silence: ‘As long as no one said a word, [Wai’s death] wouldn’t circulate. Hong Kong people were very forgetful.’ It’s a cowardly tonguelessness that shrinks from discomfort, couched beneath the sheen of Hong Kong’s ‘marble floor tiles, the brightness dizzying’. Ling is the self-avowed epitome of such clichés about Hongkongers—cynical, scornful, and detached:

“Do you think it’s inevitable for schools to switch to teaching in Mandarin? Do you think it’s inevitable for teachers to be on a contract basis?”

If it’s not inevitable, what can I do? Can writing a news story change society? Pfft! Do you think I’m one of those activists? I’m not a yellow ribbon, or a blue ribbon, or any ribbon.

‘Yellow ribbon’ or ‘blue ribbon’ refer to the political stances espoused by Hongkongers since the 2014 Umbrella Movement, the first major pro-democracy action after the 1997 Handover. ‘Yellow ribbon’ signifies support for democracy and generally ‘defend Cantonese, as it’s the most important part of Hong Kong culture’, while ‘blue ribbons’ favor mainland Chinese governance and an overt political and linguistic rapprochement with the Chinese Communist Party. In Lau’s version of Hong Kong, Ling embodies the apathetic—the politically tongueless—who are focused only on their own monetary survival: ‘Those [yellow-ribbon demonstrators] took to the streets and blocked traffic, making it impossible to get to work and do business. If you don’t need to make a living, that’s your business. Why are you so selfish, forcing everyone to do the same?’ And against blue-ribbon supporters, she thinks, ‘Since you all love Mandarin so much, why don’t you send your kids off to the mainland?’

But the trend in Hong Kong’s politics is towards mainland China, regardless of the yellow ribbons’ best efforts, and all the teachers at Sing Din Secondary School are aware of this. Sing Din’s former principal is a paternalistic British man who disparaged Hongkongers and ‘had only come to work one day a week . . . the rest of the time he was rumored to have been playing golf’. After his return to the United Kingdom, he is replaced by a business-minded, unscrupulous current principal from Hong Kong who only wears Valentino: ‘In retrospect, the principal ran the school just like a company, prioritizing outcomes and ignoring any educational philosophy. . . .’ Sheathed in apolitical rhetoric, she announces ‘that the school was moving toward internationalization and planned to switch to teaching in Mandarin after two years’. Incisive criticism of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, whose transition from British coloniality to a semi-free form of Chinese sovereignty in 1997 gave way to a local government whose leader must be vetted by the Chinese government and is titled the ‘Chief Executive’, as though Hong Kong were a company. Other employees at Sing Din, including Ling herself, collude with the principal through bribery, slander, and other forms of corruption to curry favor and silence dissent: ‘[Ling] flew to Taipei specifically to buy several bags [of coffee] for the principal and her colleagues, spending more than 10,000 HKD’ (nearly 1,300 USD). While Ling might be tongueless on the conditions of her institution, Lau isn’t.

Despite Ling’s dislikeability—disdaining Wai as a ‘weirdo,’ criticising her appearance, and abusing Wai’s earnestness to ‘help [Ling] finish all the work’—Lau’s sympathetic skill at tracing the social and historical strictures of Ling’s life portrays a pitiable, insecure character. Ling still lives with her mother in a flat overlooking a ‘sliver of Victoria Harbour . . . sandwiched between buildings, like a malformed bone-shaped diamond’. Her mother also exploits Ling to help run her ‘subdivided flat business’, renting tiny rooms to migrants from mainland China and ‘South Asian refugees’ at exorbitant prices. From Wai, to a mainland Chinese woman forced to prostitute herself in her rented room (‘Wai had wanted to turn herself into a mainlander, and this woman was born a mainlander, both from the same roots, really cheap’), Ling’s aggressive ‘disgust’ for all those different from or less privileged than her is a twisted, inherited Darwinian logic, exemplified in ‘her mom’s favorite National Geographic program’. This mimetic texture makes Tongueless stand out in Lau’s empathy with her characters, evoking a pathos beyond disgust, with an eye fixed on Hong Kong’s spiraling injustices as its boundaries with mainland China become increasingly porous.

For Ling, just as for many migrants, the ‘Hong Kong dream’ of upwards class mobility is to study, find a steady job, and earn money: ‘since she was a child, her mom had also taught her to exchange the most significant return for the least amount of effort.’ This ‘dream’ reflects Hong Kong’s history as a capitalist colony on the border of China’s Cultural Revolution, causing over a million deaths between 1966 and 1976, from which Ling’s mother fled to Hong Kong :

Ma just wants to teach you the truths of life. When Lin Biao was in power, the People’s Liberation Army entered your ma’s village. . . . Your ma is obedient—when the Red Guards wanted me to denounce someone, I denounced them. Even if that person hadn’t made any mistakes, I’d come up with a few mistakes for them. That’s why the Red Guards liked me. . . In short, when power is in someone else’s hands, be clever, don’t offend people, and then you’ll surely benefit.

In a later dream scene, Lau’s narrative confounds the memories of her mother with the persecution of Wai, merging the bloody violence of the Cultural Revolution with that of Hong Kong’s cutthroat materialism in 2019. In Ling’s nightmare, ‘Wai raised her drooping upside-down-V eyebrows and said, “Why won’t you ha-help me?” I don’t have a choice, I don’t have a choice. . .’ The tonguelessness that accumulates in Ling’s psyche throughout the novel, under pressure from her employer, her colleagues, her mother, and the society she lives in, ultimately manifests in a sinister mirroring of Wai’s fate, moving from linguistic and social tonguelessness towards the tangible, the unavoidable. Lau’s Tongueless is a masterpiece of doom—and if her depiction of Hong Kong’s linguistic subsumption seems more disturbing than the National Security Law, imposed on Hong Kong since June 2020, Tongueless, at least, is fiction.

A few characters in Tongueless, including Tsui Siu-Hin, ‘a troublemaker’ whom both Wai and Ling teach, and a journalist for the aptly named Mango Daily who investigates Wai’s suicide, refuse to be made tongueless. Tsui is in fact the only character to challenge Ling’s scorn and teacherly authority: ‘Who I am is defined by you all anyway!’ Against the bleak cityscape of Lau’s Hong Kong, ‘blood flowing from the sky’ of a Kowloon sunset, Lau’s original and Feeley’s translation ring with precision and courage, an allegorical invocation of the multiple tongues that continue to enrich Hong Kong’s language, culture, and political identity. The paradox of Tongueless is that this novel speaks out.

Michelle Chan Schmidt is an assistant editor for fiction at Asymptote and a 2023 Editorial Fellow at Full Stop, helming a special issue on literary dis(-)appearance in postcolonial cities. Her creative and critical writing has been published in Full Stop, La Piccioletta Barca, Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, The Trinity Journal of Literary Translation, and Asymptote. She updates on her writing and editorial work here.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: