In our column “Retellings,” Asymptote presents essays delving into myths, those enduring stories that continue to transform and reincarnate. In this rendition, Kanya Kanchana traces the winding path of serpents across world literature and translation in a longform lyric essay. Weaving between times and traditions, Kanya draws together the philosophical concepts, conflicting perceptions, and atavistic emotions that serpents inspire, such that we are not quite sure where one story ends, and another begins.

“In every story, if you go back, as far back as you can, to the point where every horizon disappears, you find a snake, the tree, water.”

– Roberto Calasso, Ka

When the word nāga (Sanskrit: serpent) is uttered, the first syllable must rear its hood in the air like a cobra, and the second must root into the earth like the coil it lifts itself from. The sound is the word. Where the ouraeus, the symbol of the rearing Egyptian cobra, Naja haje, is found, it’s an unmistakable mark of sovereignty, the golden hood that guards the head that wears the crown. The symbol is the deed. Sound, symbol, story—myth is the skin beneath the skin of the world, that which shapes from within.

*

Nug-iii-ni, rasps Voldemort, barely visible nostrils flaring on his flattened, cold gray face, blunting and grinding the first syllable down to a nub, elongating the central vowel to match the length of his pythonesque, yet venomous, serpent. It’s like calling a snake snaaake. The snake in question is not even a fully fledged snake. Denied identity, agency, or even a real name—nāginī is a common noun for female serpents—she’s an accursed Maledictus. Can anything that starts in mal– be good here; we’re a long way from mal’ākh (Hebrew: messenger, angel). She’s also a Horcrux (all those throaty, hatched consonants—green h, brown-black rs, black x), a bioengineered container for the uncontainable, a piece of Voldemort’s soul.

It’s no surprise. The whole series does snakes dirty. The unnamed basilisk blinded by Dumbledore’s named phoenix Fawkes in the Chamber of Secrets is also serpentine, also female, also deadly venomous. Slytherin House never stood a chance—the Hogwarts founder, one of four they’re named after, was called Slytherin, after all. Dark green and leaden, watery silver their colours—alchemical colours associated with old, and often dark, magic—set against the lawful, leonine red-and-gold of Gryffindor. Some can speak to snakes in the rare Parseltongue. Feared and reviled, the tongue sounds like a nest of aspirated sibilance, a malignant rhubarb rhubarb. In Harry Potter, the ability is a contamination.

Rowling is not making up something new here, of course. She’s merely standing upon centuries of well-ploughed, bedevilled snakery, sowing yet another potent seed in proven fertile earth.

*

*

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” But before the beginning was a snake, was it not—a snake in a tree perhaps, a snake in a body of water, a snake and a woman. Marduk has slain Tiamat; Thor has slain Jörmungandr; Indra has slain Vṛtra, but there are more.

Eden. A man and a woman in a garden that Yahweh planted. Not a forest, but a beautiful walled garden. It holds a great number of fruit trees, but two are significant—the tree of life and the tree of knowledge. The tree of life bestows immortality upon those who eat its fruit. The tree of knowledge yields knowledge of good and evil. But what’s this, the tree of knowledge is absolutely forbidden—the only one Yahweh has marked so. Couldn’t they have eaten just the first fruit and been immortally happy? Couldn’t they have at least eaten the first fruit first for insurance, and then the second, consequences be damned? Perhaps. We only learn that this is not what happened. A great, towering serpent—with eyes lit as carbuncles, says Milton in Paradise Lost—tempts Eve to eat the forbidden fruit. “You will be like gods,” the beautiful serpent says. Eve eats the fruit. Adam eats the fruit that Eve, bone of his bone, flesh of his flesh, gives him. And they begin to know. Careful what you wish for. If you ask to know, you cannot stem the tide that comes. If you ask to know while still mortal, who knows what you will become.

If the knowledge is not all knowledge, but the knowledge of good and evil, what does the serpent want them to know? What does Yahweh not want them to know while knowing that it may have been knowable? How could they have known what good or evil or even knowledge meant before they eat the fruit? The original act is itself the original sin. Chaotic good and chaotic evil tend to look remarkably similar.

*

“Cave basilischium!” says the bestial Salvatore in Eco’s The Name of the Rose, “The rex of serpenti, tant pleno of poison that it all shines dehors! Che dicam, il veleno, even the stink comes dehors and kills you! Poisons you… And it has black spots on his back, and a head like a coq, and half goes erect over the terra, and half on the terra like the other serpents.”

“I asked him what he was doing with a basilisk,” says Adso of Melk, “and he said that was his business.” The squirming “basilisk” in the bundle turns out to be a black cat, an essential ingredient to brewing a love spell.

*

“The gods bring the ankh—the crux ansata, image of life—toward the nose of the king and the people. They want to transmit the breath of life. But that breath is a hieroglyph, a fixed, recurrent, unmistakable image. There is nothing vague, ordinary, uncertain. The breath, from the very beginning, is writing. This is the profound legacy of Egypt, the prisca Aegyptiorum sapientia, which has ended up imprinted on the whole of later history and has become its seal,” says Calasso in The Celestial Hunter.

Who holds the ☥ ankh? The Egyptian pantheon had some two thousand deities, most of whom do. Geb, earth, and Nut, sky. Amun, king of the gods. Anubis, master of secrets, who places it on the lips of the dead so their souls may open to the afterlife. Osiris, son of Geb and Nut, lord of the underworld, green as the Nile, before he lends his spine to the 𓊽 djed. Set, the usurper, brother and slayer of Osiris. Great goddess Isis, giver of new life to brother-husband Osiris. Shapeshifting, falcon-faced Horus, powerful son of Osiris and Isis, sometimes missing his moon eye, sometimes with a finger to his lips. Ibis-headed Thoth, healer of Horus’ eye and maker of the word. Ma’at, who holds one in each hand, against whose white ostrich feather is measured the weight of a human heart. And thus links the ☥ ankh—liquid light poured, vital breath blown—ritual to writing, god to mortal, heaven to earth, order to chaos, life to death. As one, so the other, eternally mirrored and never quite apart.

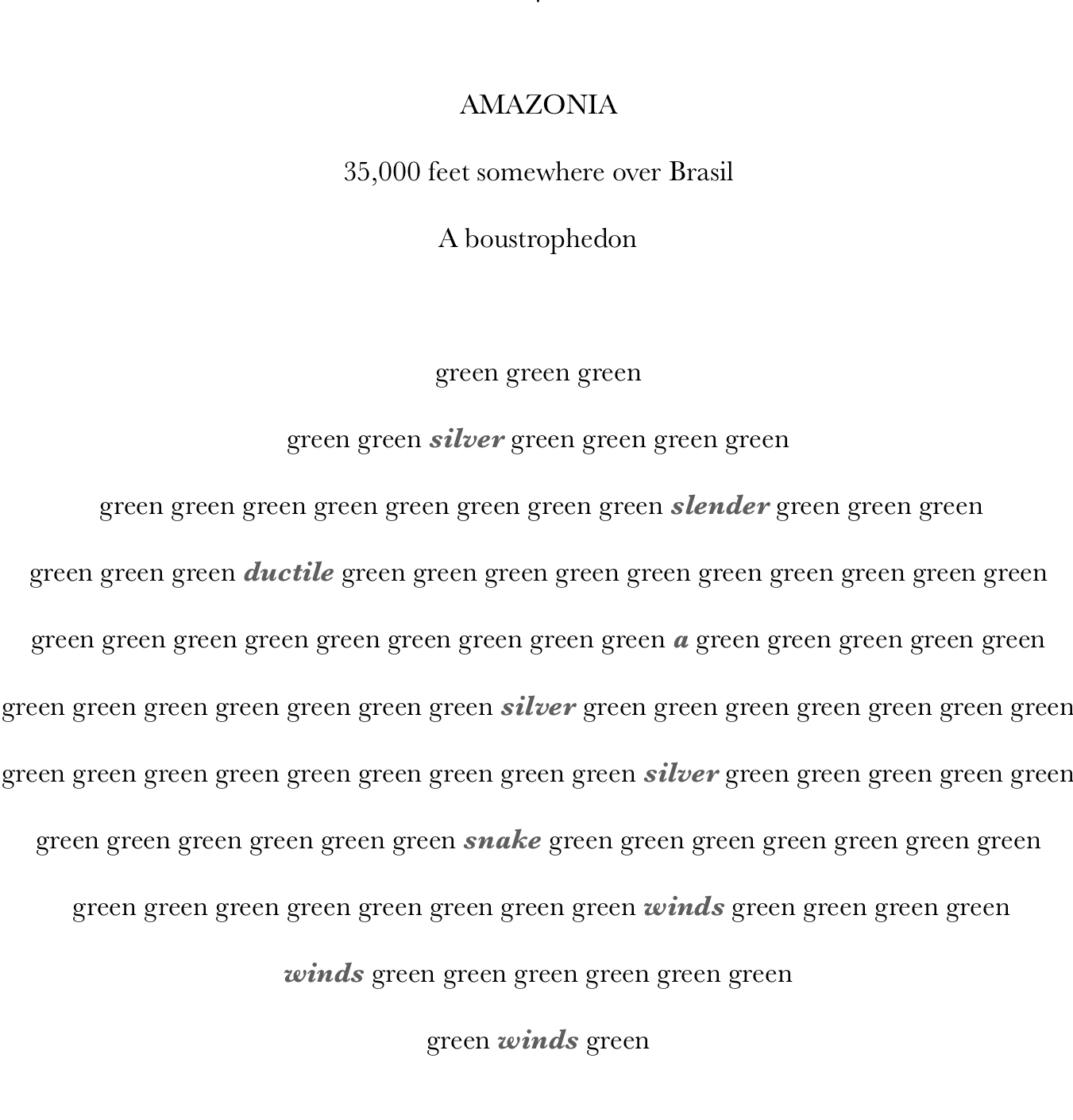

But here’s the thing: a synapse is forever between the two. They do not quite touch—they cannot—and only something ineffable can leap between them. The loop of the ☥ ankh is the Ouroboros, the endless serpent that swallows its own tail, and there is a void at its heart. Mind the gap. If Cleopatra does not kill herself with a huge cobra, beloved of Wadjet and Isis, if she does not put to her breast a small asp (Greek: aspis, viper, strangely what they called cobras then) hidden in a basket of figs (that had, if female, already assimilated some dangerous stings, what’s one more), she certainly uses poison of another kind. Does she close the gap? Who holds the ☥ ankh now? How certain are we of things?

*

“Round and round they went with their snakes, snakily, with a soft undulating movement at the knees and hips,” weaves a snake dance in Huxley’s Brave New World (a book I once read alternating pages with his Island; I could not tell which was utopia and which dystopia by the end). At the end of the dance, a young man called Palowhtiwa is whipped till he falls by a man in a coyote mask, his blood turning a long, white feather crimson. It’s a violent inversion of the Snake Dance of the Hopi.

In the sacred Hopi dance, men from Snake and Antelope clans, painted with clay and smeared with “man-medicine,” call snakes from the northwest, the southwest, the southeast, and the northeast, and cleanse them with yuca milk. Singing to them in a special language, they place them gently around their necks or in their mouths, stroke them with eagle feathers to pacify them. They dance with them for sixteen days, sending through them a message to other realms, a prayer for rain. Eagles and snakes, feathers and scales, sky and earth—no longer mortal enemies, but together in harmony. Fecund, life-giving water is not far behind.

*

Heilung close their album Drif with Marduk, a reverential whisper chant of his fifty names. Among the ruins of the Library of Ašurbanipal in Nineveh (now in Iraq) was found the Enūma Eliš, whose seventh and last clay tablet bears the fifty names of Marduk, the greatest god of Mesopotamia. “Marduk | Marukka | Marutukku | Meršakušu | Lugaldimmerankia | Nari-Lugaldimmerankia | Asalluḫi | Asalluḫi-Namtila | Asalluḫi-Namru | Du hast den Dämon getötet…” You have slain the demon, it interjects into the Akkadian.

Mesopotamia, “between rivers,” stretches between the Tigris and the Euphrates—the rivers that flow from Tiamat’s eyes when Marduk splits her in two and creates heaven and earth from her dismembered parts. Tiamat is the primordial saltwater of swirling chaos, sometimes a sea serpent, and Apsû, the fresh sweetwater she mates with to create Ea, the god of wisdom. Is a slaying a killing if it makes life? In slaying Vṛtra, what Indra releases are the waters. Marduk, son of Ea, becomes king of all gods. Babylon is built for him. His ziggurat is the model for the Tower of Babel.

Back when Ea is Enki and Ištar is Inanna, in Sumer is the Huluppu tree. A wind-uprooted tree that Inanna replants and wants to make a bed from, and a seat. But others have gotten to it first—a serpent bites at its roots, the Anzû bird hides in its canopy, and the demon girl Lilitu secretes herself in its trunk. Her brother Utu is no help. Along comes Gilgameš—the first we see him. He knows the ways of such beings—a snake had once stolen a plant of eternal youth from him and shed its skin, slithering away and leaving him mortal. He now kills the snake with his great bronze axe, setting both the bird and the girl to flight and making the tree whole again. But does one tree a garden make?

*

In Kipling’s The Jungle Book(s), there’s a lot of talk of skin. Man-cub Mowgli has several teacher-guardians, one of whom is Kaa, the thirty-foot rock python that had “changed his skin for perhaps the two-hundreth time since his birth.” Mowgli owes Kaa his life “for a night’s work at Cold Lairs,” when the snake had done the Dance of the Hunger of Kaa—a weaving, coiling, low-humming dance—casting a binding spell on the tricksy Bandar-log.

Later, an Edenic setting, where Mowgli, now accepted for the Master of the Jungle, sits as if enthroned upon Kaa’s immense, jewel-like coils, discussing skin and the sloughing of it. In a story of great treasure, “a man would give the breath under his ribs for only the sight of those things,” desire, and death, they meet White Hood, a huge white cobra with “eyes red as rubies.” No god and no girl, but the boy still learns something.

*

Loki, “the calumniator of the gods,” has three children, one of whom is the Midgard Serpent, Jörmungandr. Midgard is Earth. In Sturluson & Stigfusson’s The Poetic Edda & The Prose Edda, we learn that jörmun signifies “great, maximus, universal.” At Ragnarök, Twilight of the Gods, Fenrir, the wolf, breaks free from the rock Odin had chained him to; Hel rises up with an army of the dead from the underworld she had been consigned to; Jörmungandr, long enough to encircle the flat disc of Earth and stick his tail in his mouth, lets go and breaches the now roiling sea. All bonds are shattered and Loki’s children are together again.

Yggdrasil, the world tree, its roots chewed by serpents, has begun to tremble. Heaven has been cleft in two, and Bifröst, the rainbow bridge between Midgard and Asgard, lies shattered. Odin, who had once sacrificed an eye for knowledge, faces Fenrir. Flames leap from the wolf’s eyes and nostrils. His jaws stretch from earth to heaven and would stretch farther if only for space. Fenrir kills Odin. Thor, son of Odin, kills the Midgard Serpent, “but at the same time, recoiling nine paces, falls dead upon the spot suffocated by the floods of venom which the dying serpent vomits forth upon him.” Gods can die, worlds can end, and change is hard.

*

For Kekulé, too, the snakes dance, back when science had allies of imagination, and inspiration could come from dreams: “I turned my chair toward the fireplace and sank into a doze. Again the atoms were flitting before my eyes. Smaller groups now kept modestly in the background. My mind’s eye, sharpened by repeated visions of a similar sort, now distinguished larger structures of varying forms. Long rows frequently close together, all, in movement, winding and turning like serpents. And see! What was that? One of the serpents seized its own tail and the form whirled mockingly before my eyes. I came awake like a flash of lightning.”

He comes up with the structure of benzene—six carbon atoms in a ring on a hexagonal plane, each attached to a hydrogen atom. What scientist would admit to dreams and visions now?

*

Medusa, a mortal Gorgon, is the daughter of a sea god, and it’s Poseidon she’s with one night in Athena’s shrine. Hesiod says seduction; Ovid says violation. What we know is that she’s as Athena herself, beautiful. Athena strikes with her aegis—the one that would carry Medusa’s likeness at its centre; the one that would bend between her breasts to carry a snakechild later—turning Medusa’s hair into a writhing nest of snakes. Gaze too long into her hissing face, and human is turned to stone. Water, the first seduction/violation; snake, the second violation/seduction. What if the turn is a return?

Before it was called Delphi, it was called Pytho. And it was here that Python gave oracles. Apollo of the golden bow, four days old, lets loose the arrows that kill Python. The serpent is buried under the omphalós, the navel stone. But not before he brings up a child entrusted to him by his mother Gaea of the black earth—Typhon, now the largest and most monstrous of them all. A hundred heads and two hundred arms, a chimera made up of man, lion and wolf, bear and boar. And thousands of snakes. It’s Cadmus, searching for his sister Europa abducted by a bull—Zeus liked being a lot of things, sometimes all at once, even a snake one time that begat a bull—who finds Zeus incapacitated in a cave. It’s Cadmus who lures Typhon with his music. Stolen thunderbolts now returned to his hand, Zeus slays Typhon. Olympus is restored.

When you slay a serpent and sow its teeth, you might become one yourself. Cadmus, king of Thebes, had slain, if not Typhon, the serpent of Ares all that while ago, and now he’s transformed into a snake falling to the ground. Rearing is horizontality become verticality, a changing of planes, a changing of nature. Falling is verticality become horizontality, and the resulting thud echoes through the world. When Cadmus and Harmonia fall to the ground as snakes in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, they keep falling in Dante’s Inferno; they keep falling in Milton’s Paradise Lost.

*

Asclepius’ life begins in flames and ends in ashes. Son of Apollo, he’s pulled from his mother Koronis’ belly while her body is in flames. Zeus, his grandfather, throws the thunderbolt that reduces him to ashes for he dares to raise the dead. It’s only right that he should be a healer in between. He carries a rough-hewn staff, a tree branch really, and a single snake coils around it (Greek: baktērion, staff). The serpent can shed its skin; it can heal with its venom. Serpent in nature—the oldest symbol we have for medicine.

But the United States Army Medical Corps (USAMC) thinks: If one snake is good, two must be better, yes? All the more to hit with a stick. A flying stick with wings even, looking rather like a cross. And so the caduceus, twin snakes winding around the winged staff of Hermes. Hermes of trade and commerce. Modern medicine is a business, after all.

*

Sometimes the snakes are gone, but a snake dance appears in their place. The Kalbelias of the Thar desert in Rajasthan make a new snake dance—the men singing songs of myth and folklore, playing the pungi, or bīn, a woodwind; the women tattooed, bejewelled, twirling ever faster in embroidered, mirrored skirts. The dance may be new, but the charm is old.

*

Long before there were Bollywood films featuring icchādhārī nāgins—shapeshifting snakewomen—in tales of love and magic, treasure and revenge, and quite a lot of dancing; long before I learned the phallic significance of serpents (girl dreams of snakes, ōhō, they say, hand to flushed cheek); there was nature and myth and lore close to the ground, closer to home.

The first thing you notice is that the temperature drops. When you step off the roughly paved circumambulation path of the elegant Kerala temple, you enter a different world. Blue sky gives way to cool, densely green grove, green water body. The earth under your bare feet is no longer the red-brown coastal alluvium; it feels altogether different—gray-black and cottony soft, achurn from the invisible work of earthworms, padded with fallen leaves slowly turning to humus. Hundreds upon hundreds of species—fauna, flora, funga—grow wild together. There are rare medicinal plants. And, of course, snakes. Sarppakkāvu in Malayalam (Sanskrit: sarpa, serpent), sacred serpent grove. Beneath spreading arayāls (Ficus religiosa) and pērāls (Ficus benghalensis), ancient serpent deities carved from black granite, lone or twinned, plied with crystal salt and turmeric and sesame oil lamps. Sometimes milk, for the milk ocean. You do not take away a single leaf from the grove; you do not pluck a single flower. You protect, and in return, you are protected.

On special evenings, communities gather. Indigenous Puḷḷuva people construct enormous geometric kaḷams on the ground using coloured powder—from ground leaves of kāṭṭuveppu and gulmohur, green; from ground turmeric, yellow; from turmeric and lime, red; from rice powder, white; from charred rice chaff and charcoal, black. By golden lamplight, the puḷḷuvakkuḍam and the puḷḷuvavīṇa knock and keen; an aching song coils, “nāgamalayile nāgadeivangaḷe, kāvum kaḷangaḷum pottunna deivangaḷe…” When the tempo builds, women enter a state of trance and dance up a wild frenzy, an act called sarppam thuḷḷal. The ephemeral kaḷam is destroyed, rubbed out by the dance. Nature unfolds, healing, into ritual, and ritual folds, knowing, into nature. Night falls.

*

Whoa. Bigger than the Titanoboa, I think, longer than the T-Rex. Palaeontologists find fossil remains of a prehistoric snake, an ambush predator and constrictor that once lived in the hot, Middle Eocene backswamp marshes of what is now western India. Vasuki indicus, they call it. I think of the first snake I ever held as a child—a baby Ahaetulla, a green vine snake common to Kerala. Winding around my fingers, the little snake had raised its head and opened its pink mouth.

I see the Indian plate breaking off the supercontinent of Gondwana and drifting fast north across the Tethys Ocean, the plate that will one day crash into Eurasia, thrusting the Himalayas up into the heavens. I see the colossal serpent evolving in the old wilderness of my land, biding its time on the racing plate, the greatest snake that ever lived.

*

In Ajapālanigrodha in Uruvelā, by the bank of the river Nerañjarā, is a mucalinda tree, in which lives a serpent king called Mucalinda. It’s the sixth week after his enlightenment, and the Buddha sits cross-legged under the tree. Once, back when he was still Siddhārtha, the prince, emaciated after his six-year-long austerities, had been fed by a young girl called Sujātā. Pāyāsa, rice cooked in sweetened milk. Now as he sits under the tree, thunderheads gather above and the skies open in a cold rain that lasts seven days. Mucalinda coils himself seven times around the meditating Buddha and spreads his great hood above his head. A woman feeds. A serpent protects. What business does a Buddha have with serpents, Calasso wonders in Ka. “The Buddha’s hidden challenge was directed at śeṣa, the “residue.” Nirvāṇa is his most drastic attempt to wipe it out. Residue signifies rebirth.”

Ādiśeṣa (Sanskrit: ādi, first, primordial; śeṣa, remnant, residue) is who remained after everything ended in the great dissolution. The great serpent stretched forever and was called Ananta (Sanskrit: endless, eternal). That which remains can fill a new world. Viṣṇu rests on his coils in the primeval milk ocean. No matter that Garuḍa, the great golden bird he flies on, has a long history with snakes. If those that must not meet appear never to meet, things might be all right with the world. Viṣṇu is inbetween, the vibration of the cosmos so fine it’s a single hum.

The Devas and the Asuras churn the milk ocean for amṛta, the nectar of immortality. For a churning stick, they use the uprooted Mount Mandara, lush with green, and for a rope, they use the serpent king Vāsuki. A great many treasures emerge from the ocean, but there’s no sign of the elixir. All that back and forth and Vāsuki starts spewing venom—Kālakūṭa, the world-ending poison. Śiva swallows it. Pārvatī clutches his chest so it wouldn’t hit his heart. Viṣṇu closes his mouth so it wouldn’t kill the world. Śiva turns Nīlakaṇṭha, the blue-throated one.

The drop of poison at the heart of nectar is not an artefact or an error or a contamination—it’s technique; it’s how you burnish the work; it’s how you walk between worlds and survive. It’s the word of the serpent. Dhanvantari, the divine physician, emerges at last, holding the pot of amṛta.

*

In Vonda McIntyre’s strange, sexual, subversive 1978 Dreamsnake, a young woman called Snake traverses the post-apocalyptic, radioactive, low-tech tribal landscape with her genetically engineered snakes—Sand, a rattlesnake; Mist, a cobra; and Grass, an alien dreamsnake—using their venom to heal the sick and soothe the dying.

A novel that might not see the light of day today, it won the Hugo, the Nebula, and praise from Frank Herbert—of the serpentine Shai-Hulud of Dune—and Ursula K Le Guin. Le Guin hypothesised as one of the causes of the book’s obscurity pervasive ophidiophobia—fear of snakes. It’s perhaps appropriate that liminal beings symbolising primordial darkness, fertile knowledge, and complex transformation should precisely be the ones to inspire atavistic terror, the ones that must be slayed if things must remain as they are. Ignorance is bliss. Worldly order is restored. Or so we think.

*

Before the Toltecs and the Aztecs had Quetzalcóatl, the Plumed Serpent (Nahuatl: quetzalli, tail plume of the quetzal bird; cóatl, serpent), the Maya of the Yucatán Peninsula had Kukulkan, the Feathered Serpent (Yucatec: k’uk’ul, feathered; kan, serpent). Feathers and scales at once, sky and earth.

Quetzalcóatl and Tezcatlipoca, enormous serpents themselves, plunge into the oceans in search of the monstrous crocodile Tlaltecuhtli. Together, they rip her in two, throwing one part up to make the sky and the other down to make the earth. Her body disintegrates into rivers and plants and animals. But the earth is still devoid of humans and something must be done. Quetzalcóatl descends to Mictlán, the underworld, to gather up ancient bones to make new humans with. He must blow a conch without holes; he must trick a quail who chews the bones; he must give of his blood for the bones to live. He does them all, and humans are made—ground-up old bone, a handful of corn, and a god’s own blood.

Further down south, no realms are left behind. Where the Amazonians have the eagle, the jaguar, and the anaconda, the Andeans have the condor, the puma, and the snake. Mighty earth to keep sky and water from colliding.

*

“In the beginning, it is said, there was only the Great Serpent, whose seven thousand coils lay beneath the earth, holding it in place that it might not fall into the abysmal sea,” writes anthropologist Wade Davis about vodoun in The Serpent and the Rainbow. The word vodoun comes from the Fon of Dahomey, now Benin, and Togo. Uncoiling, the serpent moved, a great spiral that held the universe as one. He put the stars in the sky and the rivers on the earth. He moved again, and from the spring eternal within himself, he released the waters. Where the water struck the earth, the Rainbow bloomed. Ayida Wedo, the Rainbow, and Damballah, the Serpent, twined in cosmic love and stretched across the heavens, a double helix.

A double serpent may mean many things—a two-headed serpent, with both heads at one end, like in the Egyptian hieroglyphs; a two-headed serpent with one head at either end, like the cosmic anaconda Ronin; a serpent that may also be not quite a serpent, being something more; or two serpents entwined in a double helix. Anthropologist Jeremy Narby goes on to investigate the last of these in The Cosmic Serpent, “to look for the connection between the cosmic serpent—the master of transformation of serpentine form that lives in water and can be both extremely long and small, single and double—and DNA. I found that DNA corresponds exactly to this description.” Myths are often found in origin stories, but here might just be the origin story of a myth.

*

ANACONDA

Eunectes murinus

Mercado Belén, Iquitos, Peru

A triskelion within a circle

All things

to all people, Belén, one

glut away from rut

or deep rot, all

Camu-camu, aguaje, maracuya,

cherimoya, carambola, heart

of palm: in the ripe seep of plant

ichor, for your crystal

blood

Paiche, wild pig, yellow-footed

tortoise, tapir, tamarin, and

caiman: in bone and writhing

gore, for your rainbow

flesh

Agua florida, palo santo,

smoke of mapacho: in rising

vapour, for your humid

breath

Ouroboros, you ate

yourself and left

your skin

behind

Dogs, thieves,

and me, we know this

now: the potion for love

is not different from the medicine

for death

*

Tantric and yogic texts speak of kuṇḍalinī, the great energy that lies at the base of the spine, coiled three-and-a-half times like a serpent sleeping with her tail in her mouth. When she awakens and ascends the spine to the crown of the head, shattering the granthis, the knots along the way, and piercing the cakras, the vortexes, she becomes greater than the greatest of dragons. And then she descends.

Neurosurgeon and neuroscientist Rahul Jandial writes in Life on a Knife’s Edge, “The spinal cord is a beauty. You can see serpentine vessels on the back of the bright white, glistening cord. In fact, it’s whiter than the brain, which has neuronal cell bodies that look bluish grey in the cortical canopy. The spinal cord is mostly tentacles, long extensions from the brain’s neurons that carry signals. These were all tightly tucked electrical highways, and the surface showed the fine ridges.”

We’re not dragonslayers in the East. We’re dragonriders. Why waste a perfectly good dragon?

*

When the universe came alive, knowing itself as everywhere and everywhen, everywho and everywhat, a time some call Dreamtime, a colossal serpent pressed itself against the earth. It pushed, and mountains rose up and cleft the sky. It pushed, and gorges swooped down and scored the earth. From the deepest waterhole it surfaced, and long rivers went winding through the earth, dark clouds went careening through the sky. Thunderous rain fell. The sun hit the water and splintered into a thousand colours. The land grew fecund.

There were as many stories as there were peoples; there were as many names as there were stories; and the Rainbow Serpent came to be known by a great many iridescent names. It swallowed humans whole and turned bone to stone. One was drawn in Arnhem six thousand years ago, and it was seen on stone, and then it was seen on bark, on cloth, on paper. And in the Aboriginal lands, the serpent lies dreaming still.

*

OUROBOROS

I ask the medicine: Why can’t I see?

The serpent turns round and round and bites its own tail.

This night is darker than my eyes.

Aeons collapse.

The medicine replies: So you can see better now.

Kanya Kanchana is a poet and writer from India. Her poetry has appeared in POETRY, The Common, Asymptote, Anmly, and elsewhere. It has also been full-text indexed at The Columbia Granger’s World of Poetry and remixed and performed to music. Her essays have appeared in The Common, Asymptote, and Longreads. Her translations have appeared in Asymptote, Exchanges, Waxwing, Circumference, and elsewhere, and one of a 3500-year-old Ṛgvedic hymn opens a new Penguin anthology.

Kanya is also a practitioner, teacher, and philologist at the intersection of Hindu and Tibetan Buddhist tantra and yoga, with a Research MPhil in Sanskrit Studies from the University of Cambridge.

*

Credits

Cover image: Basohli Serpents, India, 17th C, Artstor

Opening illustration: Cobra, Wikimedia Commons

Closing illustration: Ouroboros, Wikimedia Commons

Poem: Anaconda, Kanya Kanchana, first published in The Amphibian Literary Journal, Spring/Summer 2023

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: