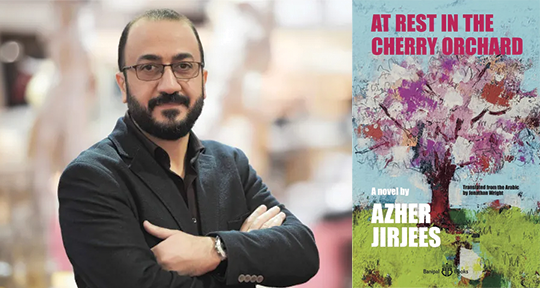

At Rest in the Cherry Orchard by Azher Jirjees, translated from the Arabic by Jonathan Wright, Banipal Books, 2024.

In 2005, Journalist Azher Jirjees published Terrorism. . . Earthly Hell, an irreverent study of terrorist militias in Iraq, against the backdrop of an expectant country. That same year, elections were held, and a constitution drafted. Subsequently, Jirjees was the target of an assassination attempt and escaped Iraq, first to Syria, then to Morocco, before settling in Norway. What might have been remains unrealized, and violence, unrelenting, pervades Iraq for years. This mix of fear and promise, all too real, sets the tone of At Rest in the Cherry Orchard, the fictional autobiography of Saeed Jensen.

The original النوم في حقل الكرز was the sardonic writer’s debut novel, and had earned Jirjees a place on the International Prize for Arabic Fiction longlist in 2020. Now, Jirjees’ rendering of an Oslo postman haunted by apparitions of his dead father, abused until nearly unrecognizable, has been sensitively translated from the Arabic by journalist and translator Jonathan Wright.

In essence, this novel is a retelling, a measured unburdening of the sequence of events that lead the protagonist Saeed Jensen to return to Iraq after his exile to Norway. Our narrator is plagued by nightmares, sleeping and waking, of his faceless father, fourteen years after his forced departure from Iraq. His daily life is repetitive, monotonous to the utmost degree, the rhythm of his comings and goings etched into the snow that reconstitutes itself each night. He works as a postman, following the same route, delivering to the same houses, tracing the same motions each day in bitter cold. He lives alone, a solitary life punctuated by appearances of his father’s ghost. An email requesting his immediate presence in Iraq sparks our narrator’s return, as he remembers his life before and since leaving.

He remembers his childhood in Baghdad where life was bitter. His mother burned all remnants of her husband’s existence and instilled a singular lesson into her son: “للجدران آذان” or “the walls have ears.” In spite of his circumstances and his father’s oppositionist leanings, Jensen secured a place in university. His university years were the happiest of his life, until he made a flippant joke to the wrong peer and suddenly his mom had sold the Singer to fund his escape.

He remembers the journey, first to Jordan, where he lived a precarious existence until a businessman walked into the falafel shop where he was working, without papers, and convinces Jensen to move to Norway, where “women melt like butter in a frying pan when they hold the hand of an Iraqi man.” He traveled by air, land, and sea to make it to Oslo, evading police dogs and strong-arming a smuggler. However, once he arrived, the snow kingdom lived up to its name, but not expectations. He froze in exile.

He remembers “Tona Jensen, the beloved whom fate had thankfully held in store . . .” If there existed a trace of justice in Jensen’s world, Tona would have delivered him from a wretched life to the simple pleasure of loving and being loved. However, his memory of her is but one blow in an onslaught of punches delivered by a world which did not care for him.

The email from his e-friend Abir is an electric shock in Jensen’s sedated existence. He had accepted that his father’s ghost, mangled until unidentifiable, would remain that way and the picture frame that should have encased his father’s likeness, would remain empty, until:

I was sure my father had died. With a stroke of a pen, some functionary had ordered him executed and now he was just a shadowy memory. But I had never considered the possibility that I might be invited to collect his remains from a mass grave.

Remembering takes another form when he returns to Iraq to claim his father’s body and leaves with a bag of bones.

I had a feeling this skeleton was the one for me . . . I had obtained an incomplete father. I took a picture of him, then put him in a black plastic bag, picked it up and left.

The chapters in which Jensen returns to Baghdad are notable departures from a highly realistic novel, flipping between the future and reality. In 2023, Baghdad is paradise and skyscrapers abound, adverts light up the streets, and a central fountain dances. In 2005, the mirage disappears, and Jensen is in a bus on the desert road to Baghdad, a city in shambles ahead of him.

Perhaps Jirjees plays with time to hint at a future that might have been if a consociationalist Iraq had managed the delicate balance of power-sharing post-Saddam. Or, perhaps, it alludes to incessant American overreach, the image of a Disney-fied client state. Or, maybe it is simply an envisioning of what his friend in exile Jamal deserved: “I remembered my friend in exile, Jamal Saadoun, and I wished I could see him to apologise for making fun of him when he said Baghdad would become Las Vegas. Jamal was right. Baghdad has become that, and deservedly so.” In any case, as readers we are left grasping. Are we awake or asleep? Are we in this world or another? What year is it?

Wright’s translation captures the estranged tonality of the narration, the matter-of-fact recounting of events and the finality of Saeed Jensen’s fate. At Rest in the Cherry Orchard adds to the established translator’s extensive repertoire of works from the Arabic, most notably Khaled Al-Khamissi’s Taxi (Aflame Books, 2008), Azazeel (Atlantic Books, 2013) by Youssef Ziedan, for which he won the Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation, and The Iraqi Christ (Comma Press, 2013) by Hassan Blasim. Wright’s dispossession of the superfluous, in this text as in others, suits the hyper-realism of At Rest in the Cherry Orchard. Perhaps this is a result of Wright and author Jirjees’ shared careers, working between journalism and translation. His touch is light, prioritizing ease of readability over strict adherence to the expansive and manipulable Arabic. This is particularly needed in a novel that blurs together–past and present, fiction and nonfiction, real and conjured. In direct and deliberate prose, Wright channels Saeed Jensen’s testimony.

It is tempting to draw further comparisons, not only between the professional lives of Wright and Jirjees, but between Jirjees and Jensen. Both were exiled from Iraq for satirical commentary aimed at the regime and found rest, in one form or another, in the land of ice. However, in an interview with our friends at ArabLit, Jirjees maintains his distance from his ill-fated subject:

One of the difficult things for an author is to determine what and how much is to be leaked from his autobiography to the narrative text he writes. We just need to face it; the author cannot prevent this leak. Indeed, some authors insert parts of their autobiography into their narrative text, making the matter confusing for the reader. I think it is legitimate, but I didn’t follow that path. Yes, there is a similarity between me and the protagonist of my novel, Saeed Jensen . . . but our lives are completely different.

Reading At Rest in the Cherry Orchard is therefore bearing witness to a life defined by upheaval and loss, and perhaps a generation of lives embittered at the hands of people in power. Each loss feels like a biting joke in the life of an exceptionally ordinary man with the most modest of aspirations: merely a life worth living. At home neither in his homeland—a trap awaiting his misstep—nor in Norway, where he is forever an incursion, Saeed Jensen can only find rest in death. The detached tonality sharpens the impact of Jensen’s desolation until the reader becomes numb to the onslaught, a coping mechanism that Jensen himself finds only in ketamine, which eventually carries him to his final sleep.

Azher Jirjees does not alleviate suffering nor balance injustice to write a palatable tale of redemption or closure. At Rest in the Cherry Orchard is required reading, a compulsory recognition of the individual injury that was the inarguable consequence of power politics in Iraq at the turn of the century. Read, and remember.

Bridget Peak is an Islamic arts and culture researcher and educator from Billings, Montana. She is an incoming graduate student in the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at MIT.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: