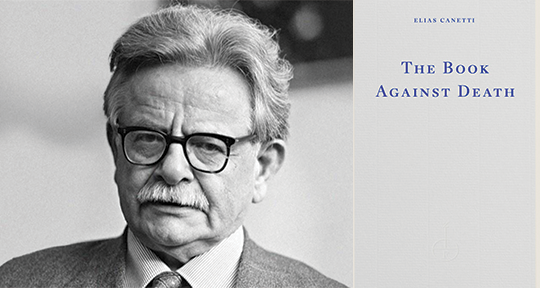

The Book Against Death by Elias Canetti, translated from the German by Peter Filkins, Fitzcarraldo/New Directions, 2024

The fact that the twentieth century saw the greatest number of conflict-related deaths in human history might be considered fundamental in explaining the over two-thousand pages Elias Canetti wrote in preparation for his book against death. However, reading the abridged version—published by Fitzcarraldo (UK) and New Directions (US)—one will find that Canetti would object strenuously to this causal explanation. This relation between factuality and literature, Canetti would say, concedes far too much to death in two ways. Firstly, it allows death quantity: by remarking on the sheer numbers, we suggest that the tragedy of death is quantifiable; that the more death there is, the greater the tragedy. Secondly, it allows death quality: by remarking on the specific kind of death—those caused by conflict—we suggest that its calamity is measured in part by the nature of the dying. To Canetti, a lone Don Quixote who ceaselessly struggled for life in a century of death, all death is singular and its tragedy is infinite. In order to better understand this, we must turn to one death: his mother’s.

June 15, 1942

Five years ago today my mother died. Since then my world has turned inside out. To me it is as if it happened just yesterday. Have I really lived five years, and she knows nothing of it? I want to undo each screw of her coffin’s lid with my lips and haul her out. . . I need to find every person whom she knew. I need to retrieve every word she ever said. I need to walk in her steps and smell the flowers she smelled, the great-grandchild of every blossom that she held up to her powerful nostrils. I need to piece back together the mirrors that once reflected her image. I want to know every syllable she could have possibly said in any language.

Canetti (a man who despised Freud and referred to the Oedipus complex as “hackneyed prattle that no one failed to drone out”) took the cataclysmic death of his mother not as a personal aberration but as the emotive standard that every death deserved, regardless of circumstance or victim. He was born to two Sephardic Jews—Jacques Canetti and Mathilde Arditti—in the Bulgarian port town of Ruse in 1905. The family’s surname is derived from Cañete, a small village in La Mancha (coincidentally, Cervantes was his favourite novelist and Don Quijote his favourite novel); after the Reconquista and the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, Canetti’s ascendants made their way along the Mediterranean—changing the spelling from Cañete to Canetti in Italy—until settling in Ruse. There, Canetti learnt his first languages: Ladino—the language of the Sephardim—and Bulgarian. In 1911, his family moved to Manchester so that his father could manage a trading business, but after he abruptly died of a heart attack in 1912, they moved to Lausanne. These departures came to define Canetti’s life, as he peregrinated through Vienna, Zurich, Frankfurt, Berlin, and London for the rest of his life, learning English, French, and German along the way.

Ultimately, it was German that Canetti came to write in, though he published little—relative to his output—in his lifetime. These works include one novel, Die Blendung (The Blinding, translated into English as Auto-da-Fé), in 1935, various plays, a three-part memoir, and a study of group psychology entitled Crowds and Power. Yet, his life was defined by a work which he never finished—one that he knew he could never finish: that tentatively titled The Book Against Death. From 1937 to 1994, the year of his own passing, Canetti wrote notes almost every day in preparation for this work. Later, over two thousand pages of notes were discovered, and out of these, a selection of roughly three hundred pages was published in its original German in 2014. This is the text that will soon arrive to English-language readers, translated by Peter Filkins.

The resulting text is unique, taking the form of the German Aufzeichnungen—an aphoristic compilation of notes and records; it is not The Book Against Death that Canetti worked his entire life to produce, but the notes he had made in preparation, and the resulting formlessness reflected the author’s intellectual habits and graphomania. In 1942, Canetti recorded his decision as follows: “Today I decided that I will record thoughts against death as they occur to me, without any kind of structure and without submitting them to any tyrannical plan.” He was proud to reject the dominant totalizing narratives of his era, and considered a defined form as suffocation, tyranny, or death itself; Aufzeichnungen, then, allowed for spontaneity and the open-endedness of life. This culminated in a text composed of pithy one-liners (“He shed tears for a friend whose name he had forgotten”), diary entries, extracts from anthropological and historical works, and extended reflections on his life and his milieu (there is scarcely a male German-language writer that Canetti does not mention at one point).

The Book Against Death at points resembles Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations—another aphoristic, posthumous work that was put together by the writer’s estate. The difference, however, was that Anscombe assembled Wittgenstein’s notes in order develop an argumentative thread throughout the work, while no such conceptual progression can be found in Canetti’s compilation—nor could there be, as its premise is that a sustained argument against death would be to meet death in its own domain. Instead, The Book Against Death represents something of a guerilla campaign: the death of death via a thousand cuts, with the weapon of a thousand aphorisms and ephemera. To read it is to experience a sustained, gradual expansion of one’s conception of what death is, and the role it plays in human life.

Death, to Cannetti, is not one part of what we might call a life-cycle, but rather a metaphysical mistake. In the first of his notes, he staked himself out as a partisan on behalf of “the defense of the human in the face of death”, thereby establishing that death is not part of the human, but an intrusion on it. Our goal, or our proper state, is immortality. Canetti is unequivocal in this, writing that “no one should ever have had to die” and that there is no crime that merits death. The singlemindedness and zealotry that Canetti brings to his crusade against death is the engine that sustains the work, as he refuses all rationalizations of death—religious or secular—and affirms each death as an irreversible rupture. Surmising that the difficulty of death leads us to platitudes and false consolations, it is notable that mourning is mentioned only once, and in passing; it is as if the only form of mourning Canetti could countenance was The Book Against Death itself—that the pain of loss was not a wound to be healed but a weapon to be wielded. This extremism is what sustains the work, but also what hampers it in the end. By characterizing death as alien to human life, he makes it incomprehensible in a way that is hard to take seriously beyond literary terms. To “make no distinction between the dead” is to empty and flatten death, rendering it ineffable. In this way, Aufzeichnungen was the only form through which Canetti could write about the subject, as he made it unknowable and thereby resistant to any sustained, structured treatment.

If there is no distinction between the dead, however, there is in death itself. There is something fundamental and important in affirming the difference between the murder of a child and the dormant death of an octogenarian. The circumstances, the timing, and the subjects of death are not, as Canetti declares, contingent; they are an ineluctable part of how we understand death as phenomenon and as tragedy. To solely treat death as a metaphysical state of universal equality is a failure to grasp it as material reality we each undergo and are affected by, as death is not just something that befalls us, but something we inflict on each other. Canetti speaks of Auschwitz but he does not speak of the Nazis, an omission that hangs over the work, upon which we must ask: can one be an opponent of death without naming the instigators of death? His calls, then, for the pursuit of immortality seem glib in a world where a normal human lifespan is denied—through bombs and bullets and famine—to so many.

The work does have one defining formal element: the entries are presented under the year they were written, in chronological order. Through this, The Book Against Death becomes a diary defined by a single subject, the morbid equivalent of Annie Ernaux’s Getting Lost. Canetti’s thoughts on death do not develop much beyond the first hundred pages, but what becomes of interest is how the work outlines the shape of one man’s obsession throughout his life. Death was Canetti’s sun, and The Book Against Death is a picture of the world on which it shone, and the shadows it made.

Throughout, history and personal life break through. He reflects on the Six-Day War and the ethnic cleansing of Bengalis during the Bangladesh Liberation War. In the 60s, for the first time in his life, he becomes infatuated with a woman, Hera Buschor, and the entries decrease significantly. In 1972, he has a daughter, Johanna, and from then on his notes are coloured by the overwhelming fact that he has brought someone to life, and the recognition that someone might mourn his death the way he mourned his mother’s. Further on, the entries from the final two decades of his life become more prodigious as his own mortality comes into view. His entries turn from the second-person plural to directly address himself, as he laments and resents his inability to write The Book Against Death. The reader joins Canetti in the realization that in writing about death, he was always writing about himself.

In one later entry, Canetti remarks on his reading habits:

For some time, I have loved nothing better than to read the lives of the saints. They are figures in the truest sense, with nothing modern about them, forever unchanged, contorted with pain, but not corrupted, single-minded, immortal in their defiance.

With this most recent translation by Peter Falkins, Canetti secures how he will be remembered—indeed, how he will manage to defy death: contorted with pain but not corrupted, single-minded and immortal in his defiance.

Sebastián Sánchez is a Chilean-American poet and translator and Asymptote’s Assistant Interview Editor. They have most recently had their work published in Protean Magazine and the Oxford Anthology of Translation. They run a translation blog, de Rokha & Others, where they publish translations of Chilean poetry. Their translations focus on poetry published and written by Chilean women and queer people in the 70s and 80s during the dictatorship. These poets and writers (such as Soledad Fariña, Malú Urriola, Diamela Eltit, and Pedro Lemebel) used their position of social oppression and political repression to develop radically innovative forms of writing which expanded the possibilities of what language can do and are deeply underappreciated in the Anglophone world.