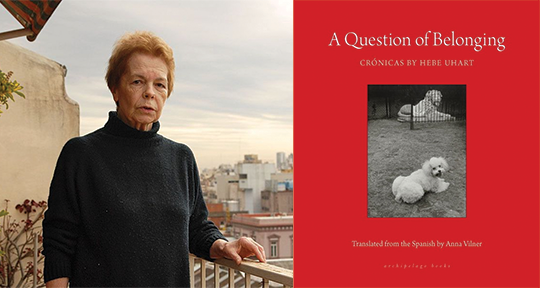

A Question of Belonging by Hebe Uhart, translated from the Spanish by Anna Vilner, Archipelago Books, 2024

A Question of Belonging, the recently released collection of crónicas by the late, acclaimed Argentine writer Hebe Uhart, offers a unique alchemy of attentive reportage, sociological and psychological insight, and incisive wit. Drawing readers in with her ability to enjoy the unexpected without judgment, Uhart continually combines humor and erudition to recreate her encounters with camaraderie and guidance, and the care she extends to vulnerable strangers is all the more self-evident when contrasted with her willingness to eviscerate pernicious cultural narratives, particularly those that serve to harm and diminish. The translation by Anna Vilner captures the tonal nuances between these modes, as well as Uhart’s authentic political sympathies—most notably with marginalized and indigenous peoples, from whom she continually attempts to learn.

Crónicas on trips ranging in destination from Río de Janeiro to the Peruvian jungle are supplemented by visits to various therapists, a “North American Professor,” and a hospital stay. Uhart’s integrated practices of reading—which include the interpretation of not only books, but people, relationships, and the self—intertwine in these textual sojourns, often revisiting the ego’s haunts, assumptions, and habits in correspondence with the journeys they narrate. Such practices deepen interactions with differing views, histories, and community structures, truly exemplifying an openness to challenge and newness. The results mirror the process itself: shifting, dynamic essays that act as flexible containers for both journey and reflection, while leaving ample space for the reader’s own impressions and discoveries.

The subtle shifts of concurrent observation and self-reflection are quickly apparent in “A Trip to La Paz”, in which Uhart narrates a conversation with an oddly dressed teacher on the train: “I quit judging her inappropriate outfit. When she spoke, she was overcome by a kind of indignation that made me see her dignity.” In claiming not to judge something while calling it inappropriate, Uhart foregrounds her own contradiction, presenting herself as self-aware rather than magnanimous. Immediately after, however, the echo between “indignation” and “dignity” mirrors the woman’s complexity; Uhart respects her, in part, because she advocates for the underfunded public school where she teaches, as opposed to the “private schools” with that enjoy “every luxury there is”. Moving beyond her primary, superficial analysis, Uhart deepens her emphasis of the woman’s character by revealing the context of her own privileges, which may have been connected to her understanding of appropriate train attire: “Both of us were teachers (I was just starting out), but while she lived off her poor salary, I spent mine on travel and buying whatever bullshit caught my eye.”

Such tonal modulation also facilitates passages that sway gently between sociology and satire. On its surface, “Inheritance” offers a tour of downtown boutiques: “The garments are always the same shape and length; every week, the owners change the color scheme. It occurs to me that this taste is also inherited, passed down from a time when women dressed to please rather than offend.” This commentary on tradition seems straightforward until Uhart rather seamlessly arrives at what appears to be an oppositional perspective: “Nobody goes into that shop either, they go into the shop next door that sells skirts with studded red flowers, asymmetrical ones, others with ruffles. Because nobody cares about offending others these days, nobody cares much about anyone.”

This responsive satire of our tendency to equate chronology with progress artfully points out that neither state—whether it be caring too much or no one caring at all—seems ultimately desirable. However, as the humor moves us beyond both assumptions, we encounter a deeper apprehension of our competing needs for security and change: “One is inspired to buy those outfits and dress up in a different color every week, like the display window, to harmonize the soul, to have things change without really changing, to perform a ritual that ensures eternity.” Linking clothing choices with eternity, partially due to its ridiculous logic, opens a vulnerable awareness of how our need for interpersonal connection underlies our attachment to customs, regardless of their objective merit. In a deft reflection of this continual process, mortality thus insinuates itself surreptitiously into the passage through the very fallacies often used to guard one’s consciousness from it. Amazingly, we can empathize with the customers in a deeper way after embarking on Uhart’s tour, which initially seemed to mock them.

“New Year’s in Almagro” displays a similar agility between humor and insight, from its opening, rather idiosyncratic view of Christmas:

Christmas and New Year’s awaken altruistic feelings in me. I am reminded of the people in the world who grow up, suffer, and die, and I cease to think of myself as the center of the universe . . . This altruism has a certain poetic uselessness, but I manage to give it meaning. I am aware of the many people in the city without electricity, and others who go without gas or a roof over their heads. I don’t do anything to help them. How could I manage to fix all of their problems? But if I am going to dinner at an expensive restaurant, universe . . . I first take a dip in the seedy dive bar out front, where I have a coffee.”

Characteristically, Uhart resolves her satirical division between the sentimentalized holiday and its discordant earthly contexts by taking an excursion, albeit a shorter one in this case. She seeks answers—to the extent that they exist—in new perspectives, which often turn out to illuminate something more interesting. This particular outing is less depressing than rumination, and her patronage and attention support others in practical ways, though her humor dismisses any moral self-congratulation. Without guilt or aggrandizement, she fills the “expensive” dinner with an intuitive observation of the men at the next table. An “older one seems grateful for his luck”, and Uhart imagines him thinking: “Luckily I can afford this meal. . .”; in contrast, his younger companion, “looks like he studies something cerebral, like philosophy. His knowledge casts a shadow over his eyes and forehead—surely he must be thinking that everything around him is a display of vanity. What is the glue that holds them together?” In these observations Uhart does not attempt to resolve the previous inner conflict between class consciousness and indulgence, but gently broadens it in this an unquantified engagement between her intuitions and people in the world.

An important quality of Uhart’s writing is that she facilitates such processes without polishing their contradictions, slippages, and paradoxes; her conception of truth-telling clearly holds an imperative to bare the process of the telling itself. Accordingly, her craft of highlighting internal tensions (either her own as a writer, or those shared more broadly with subjects and readers) serves as an essential and paradoxical consistency within the writing. It is also a subtle model of writing as a practice in which the mind may return to itself—because it has changed along its way.

This flexibility of perspective is essential to Uhart’s interactions with indigenous peoples, which make up some of the most pointedly political content of the collection. “The Jungles of Lima” exemplifies her willingness to see Western assumptions from other points of view. In working to connect them to her own experiences, she also illustrates possibilities for coexistence:

Unlike the way of thinking in the West, where it is held that human beings and animals have a common past, but that man ultimately triumphed over his animalness, so to speak, here humanity tends to be attributed to animals, to the wind, to inanimate objects even. Karina Pacheco writes: “The sun began to sing in the voice of a cicada,” and later: “It began singing in its jaguar voice.” According to the Brazilian anthropologist, it is not perspective that makes this cosmovision different from our own, but the world itself. It turns out that forms are at the mercy of forces, and forces change form to manifest themselves as they wish. The rain, the sun, even rocks speak to me. If everything speaks, if everything has something to tell me, the first step to making a decision and to being sure of how I feel is to take a look around—a heron’s squawk might give me the answer. It seems strange, but it isn’t really. In the past, when I was confused about something, or felt a sense of disquiet, all I had to do was observe my cat’s behavior to understand what was going on in me.

Through her compassionate attention, Uhart learns through both textual and human interaction—and amalgamates the two in a likewise seamless manner over the course of the passage. It’s also important to recognize the understated connection between the objectifying of animals—who are thought by some in the West to have less “humanness”—and the denial of rights to indigenous peoples, who recognize the personhood of those animals. Uhart’s conclusion illustrates that this is not an ideological dispute, but rather an instance of prioritizing ideology above the lives over which it is imposed. For her, this perspective impoverishes its own capacity for meeting life anew in the other:

Peruvian writer Faniel Alarcón suggests that the greatest difficulty the guerilla fighters faced in the jungle was not combat, which was rare, but the heat, insects, and the stretches of time spent waiting, listening to unknown sounds—these were the real enemies.

I would go the jungle if only to do that, to listen to new, unknown sounds.

Several of the narratives also address various historical and cultural elements as contexts of contemporary indigenous life. “I Didn’t Know” narrates a visit to a community in Uruguay, featuring a local woman who had worked as a “health-care agent” until she was fired due to an “insubordinate” response to discriminatory practices. Uhart introjects, “An important clarification here. They are not insubordinate now, nor were they back then. Mass killings were carried out in the 19th century to rid them of their land; the final one happened in 1914.” This quick transition from present to past mirrors the recurring trauma of relatively recent history in the daily lives of the community, just as the government “registry”—also dating from 1914—lives as an ongoing torment, stifling the “speaking of our indigenous background.” Uhart’s political stance is as unequivocal as her listening is subtle.

In their gentle exploring, the crónicas often evoke the pernicious effects of overreach into lives that have their own functioning structures. The ending of this piece, however, points toward an opposite danger facing such communities—one that Uhart’s work does intentionally counteract: “What I do know is, when we returned . . . , I told four different people that there was a Charrúa community in Maciá. All of them said the same thing: ‘I’ve been to Maciá, but I didn’t know about that community’.” Here, Uhart exposes one of the deepest cruelties inflicted upon the indigenous peoples, their being compelled by threat into acts of self-preservation that slowly enact their own erasure.

These are not moralizing pieces, yet Uhart exemplifies consistent values—most evidently an openness to the other and a suspicion of prejudice and sentimentality. She accommodates a diversity of meetings through an array of observations, speculations, interpretations, and empathetic intuitions, organically informed by texts that range from learned to quirky. The crónicas gathered in this collection present a kind of mutable home within these encounters, always seeking a life outside of what is already understood, while returning to their invisible companion: the reader who tags along on the adventure, as a student, confidant and co-learner.

Michael Collins’ poems and book reviews have appeared in many journals and magazines. He is also the author of several books and chapbooks, including Appearances, which was named one of the best indie poetry collections of 2017 by Kirkus Reviews. He teaches at New York University and various community outreach and children’s centers. He is the Poet Laureate of Mamaroneck, NY. Visit notthatmichaelcollins.com.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: