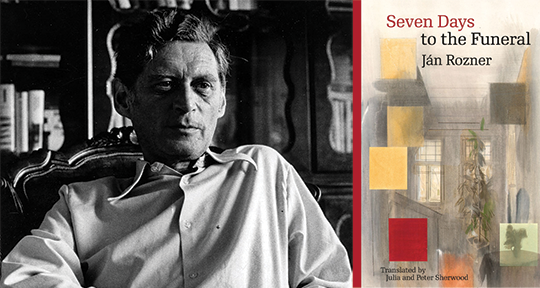

Seven Days to the Funeral by Ján Rozner, translated from the Slovak by Julia and Peter Sherwood, Karolinum Press, 2024

In 1968, troops of the Warsaw Pact—led by the Soviet Union—invaded Czechoslovakia to crush an ideological rebellion against Communist orthodoxy, bringing the daring freedom movement to to its inevitably violent end. The world would come to define that era as the Prague Spring, yet as well as the subsequent arrests, heavy censorship, and exile for many intellectuals affected not only Prague, but also Bratislava and the whole of Slovakia—the eastern part of what was then one country.

In the foreign imagination, Slovakia largely remains in the shadow of Czech narratives—something Prague-centric fiction and non-fiction have long perpetuated. The recent translation into English of Seven Days to the Funeral (Sedem dní do pohrebu), by Slovak author Ján Rozner, fills this major gap in the perception of post-1968 Slovakian and Bratislavian intellectual life. In a four hundred-page long autofiction, meticulously and elegantly translated by Julia and Peter Sherwood, Rozner provides a rare testimony against the blind spots of collective history and memory—including those, as it turns out, of Slovak readers.

What is particularly striking is how the shape and the style of Seven Days to the Funeral espouse the despair and dread of what was experienced in Czechoslovakia as “normalization”—party-speak terminology used to describe the post-1968 period of obsessive governmental control, enacted to ensure that any dissent against Moscow would never again be possible in Central Europe. This translated into the elimination of any possible contest or alternative culture, be it intellectual or religious opposition, or simply works of music, literature, or art. However, as the dissident movement (with Václav Havel and the rebellious manifesto of Charter 77) proved, the liberating aspirations of underground gatherings, samizdat literature, and civil uprisings would eventually triumph three decades later, in the Velvet Revolution.

But in 1972, the year in which Rozner’s book takes place, hope was not a realistic commodity—for intellectuals in particular. And thus, Seven Days to the Funeral starts with an absurd and real-life situation emblematic of the period: the main protagonist of the story, also named Ján Rozner, loses his wife Zora to a long illness on Christmas Eve. While all he wants is to be done with the funeral quickly, a legion of obstacles quickly accumulate to make the business of death as cumbersome and complicated as possible, stretching it over seven very long days. Written in a diary form, the novel is divided into chapters defining each specific day of the long wait, beginning with the day and evening in which he finds out about his wife’s death. Framed by the rituals of breakfast and going to bed, often accompanied by alcohol, each chapter is in itself a whole life remembered in the constant intertwining of two narrative lines: the dreadful minutia of organizing the funerals, and the remembrance of a deeper past—whether it is the shared life with Zora, or even earlier memories of the narrator’s childhood and youth.

The first line of narrative reads as an absurdist, never-ending list of social and administrative obligations, all of which seem to have the sole purpose of prolonging their procession. The narrator finds himself alone and clueless about the business of funerals: he has no children, and has lived in relative isolation from mainstream society. He receives orders from the extended family, colleagues of his wife, and external players seeking to make money, eventually ending up running a long marathon of tasks in the context of a Christmas week, when administrations and families are more preoccupied with taking time off, cooking festive meals, and visiting one another. While attempting to get paperwork stamped in various offices, Rozner is also faced with the issue of writing a eulogy for his wife, a renowned literary translator and well-known intellectual figure—albeit censored at the time of her death for her political activities in the late 60s. This makes the delivery of the eulogy a sensitive matter, as the person delivering it at a public event might be severely punished for siding with a political enemy of the people. In fact, one of the readers of the eulogy, a professor of Italian literature, will indeed lose his job after the funeral.

Then there is the question of a religious or a civil funeral, the choice of music to be played, and even the issue of a death mask—and in how many copies. The endless list and the increasing pressure of the seven days create an interesting tension, but also serve as a realistic document describing the absurdity of living in normalization, in which a paranoid state’s appendages remain constantly present.

The second main narrative line operates around the evocation of multiple pasts: the life of the couple, their careers before and after 1968, and their own familial histories. Through vignettes and numerous portraits, Rozner constructs a play in many acts—a form he himself acknowledges towards the end of the book. The main character of that play is Slovak society, undergoing the traumatic historical events from the ‘30s to the early ‘70s: being part of the 1918-1938 Czechoslovak Republic, becoming a puppet state under Nazi control until 1945, reintegrating a capitalist Czechoslovakia from 1945 to 1948, and finally entering a socialist period from then on.

The testing grounds of this often tragic history is the capital, with its many names reflecting an originally multi-ethnic history: Bratislava in Slovak, Preßburg in German, Pozsony in Hungarian. The book also paints the ever-tenuous urban landscape as a theater of erasure. Many Czechs departed after 1938. German was widely spoken in the nation by both ethnic Germans and Jews alike until 1945, but that memory was shamed and obliterated in the aftermath of World War II. At that point, many squares, streets, cafes had to switch to Soviet names to align with the political agenda of the period, rejecting the bourgeois memories reminiscent of Austro-Hungarian or independent Czechoslovak periods. The narrator-writer is himself of mixed German-Jewish heritage; having married a woman from a culturally well-established Slovak family, he also initially experienced the same rejection and suspicion from his in-laws.

Throughout, the book reveals these layers of history gradually to reveal the zeitgeist of 1972, but the most telling aspect is the abysmal and bitter absence of any escapism. Be it an idealization of the countryside, burying oneself in academia and translation, pursuit of exile, or intellectual resistance—all such roads are dead-ends, because normalization will not allow any form of individual life, public or private.

Through Zora, Rozner illustrates how the state is able to reach into any of the nation’s corners, even as individuals sought freedom by opposing urban society. Zora died in a Bratislava hospital, but made it clear that she wanted to be buried in Martin, a small city close to the mountains where her family vault had been built. Despite her marriage to Ján, who resided in the capital, Zora had spent most of her time in Martin, and clearly expressed her disdain for the suffocating life in Bratislava. Both Czechs and Slovaks have a long tradition of the chata—the countryside chalet; such places acted as refuge for many persecuted intellectuals, who would move there for long periods of time in hopes of breathing more freely. However, secret police never failed to surveil them wherever they went, controlling visitors and embedding listening devices in their homes. Zora’s family home is eventually rented out to a policeman, accentuating the fact that there could be no haven from persecution.

Another significant form of the state’s imposition was how literary translation became an avenue towards internalized exile. After 1968, many professors, writers, journalists, and artists were banned from appearing publicly or occupying professional posts, and thus one way to survive, both economically and intellectually, was by translating books. Jan and Zora had bonded while translating Shakespeare into Slovak, and Zora had been a major translator from French and Russian—a founding figure for generations of translators. But after 1968, it became impossible for either Ján or Zora to take on work, or to even have their names mentioned in public:

With the onset of normalisation, Rozner and Jesenská, like many other intellectuals who refused to conform to the regime, were gradually deprived of every opportunity to work. Publishers stopped commissioning translations from them, their names could not be uttered in public, and their books were withdrawn from circulation, including from bookshops and libraries. They also found themselves ostracised in their private lives, shunned by some of their friends and acquaintances, and found little understanding of their principled stance even among their relatives.

When Zora finally agreed to live full-time with her husband in Bratislava, she became a model housewife, keeping the flat in a state of perfect cleanliness and impeccable style, throwing herself into creating a garden on an adjacent slope, and furnishing their home with books, LPs, and cacti. (The latter is a telling symbol of the period; anyone who lived in Czechoslovakia in the 70s and 80s can attest to a national mania with collecting, exchanging, and displaying cacti in their windows.) Rozner’s diary form underlines such small details—of buying and cooking food, repetitive habits, Christmas rituals. It is only in this, the routine of daily life, that one finds reprieve from authoritarianism. With the death of Zora, Ján’s domestic shelter is drained of its comfort and impressed with absence, and through this we understand the depth of the author’s grief—a loss that stems not from a perfect partnership, but from two people who understood one another, providing rhythm to a life that was made pointless by a lack of work, a stunted freedom, and a society that had shut out its most honest voices.

The translators deserve special mention for their momentous work (with a disclaimer that Julia Sherwood is my good friend). Julia and Peter Sherwood have opted to keep several Slovak words in the original, a choice that not only honors their reference to very specific cultural contexts, but also reminding the reader that this is a translation of a book about translations and translators. It is also notable that Julia is directly connected to Ján and Zora; she is mentioned in passing within the story, and her mother is one of its important characters.

Overall, the book is a rather grim—but deeply honest—account dedicated to the documentation of post-1968 intellectual life beyond Prague, and how historical events have led to a significantly diversified Slovakian society. The narrative is followed by supplemental materials that give way to some of this richness: a list of intellectuals sometimes not fully identified in the original text; a few black-and-white photos of Ján, Zora, and her family; and a condemning article written by Zora Jesenská titled: “The First Resolute Show of Force by the Police of the Slovak Socialist Republic.” It also adds an afterword by Ivana Taranenková that provides a historical framework, as well as some background to the text itself—a lost manuscript released three years after its author’s death in 2009.

Given that Rozner eventually moved to Germany and never returned to live in Slovakia—even after the end of Communism in 1989, Seven Days to the Funeral reads today as a particularly poignant take on nostalgia. Through the painstaking detailing of his former life, one senses that the author had resurrected the city that shaped him only to situate it firmly in the past, as an essential portrait of those years lived in silence.

Filip Noubel was raised in a Czech-French family in Tashkent, Odesa, and Athens. He later studied Slavonic and East Asian languages in Tokyo, Paris, Prague, and Beijing. He has worked as a journalist and media trainer in Central Asia, Nepal, China, and Taiwan, and is now based in Taipei as Managing Editor for Global Voices Online. He is also a literary translator, interviewer, editor-at-large for Central Asia for Asymptote, and guest editor for Beijing’s DanDu magazine. His translations from Chinese, Czech, Russian, and Uzbek have appeared in various magazines, and include the works of Yevgeny Abdullayev, Bakh Akhmedov, Radka Denemarková, Jiří Hájíček, Huang Chong-kai, Hamid Ismailov, Martin Ryšavý, Tsering Woeser, Guzel Yakhina, David Zábranský, and Zhang Qianfan amongst others.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog:

- In Spite of It All: On Czech Comics with Pavel Kořínek and Michal Jareš

- “Liza seems to want a bright future, not just a virtual imagination”: An Interview with Slovak poet Zuzana Husárová

- Publishing in Slovakia