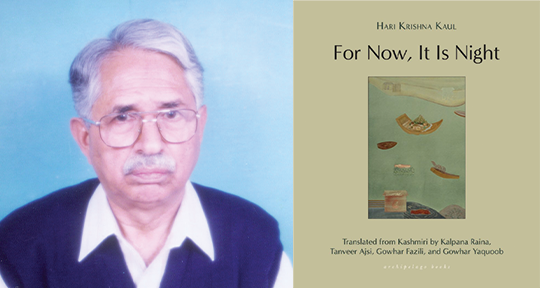

For Now, It Is Night by Hari Krishna Kaul, translated from the Kashmiri by Kalpana Raina, Tanveer Ajsi, Gowhar Fazili, and Gowhar Yaqoob, Archipelago Books, 2024

Hari Krishna Kaul (1934-2009) was a Kashmiri writer dedicated to inscribing the quotidian lives of people in the valley, releasing their stories in both fiction and dramatic works throughout his life. Some of these pieces have now been collected in For Now, It Is Night, which features seventeen stories picked from the four collections spanning Kaul’s career—two written and published before the watershed year of 1989, while the writer still lived in Kashmir; and two published after he and his family had migrated—just like many other Hindu families—in the Kashmiri Pandit exodus, which occurred upon the onset of militancy and rise in communal tensions after India’s Independence in 1947. As Kalpana Raina, Kaul’s niece and one of four translators in this volume, writes:

There are no grand themes in Kaul’s work, but an exploration and an acceptance of human limitations. He used his personal experiences to explore universal themes of isolation, individual and collective alienation, and the shifting circumstances of a community that went on to experience a significant loss of homeland, culture, and ultimately language.

One would assume that Kaul would become prejudiced after his exile, but that could not be farther from the truth. As Gowhar Fazili, another translator, states: “Unlike a partisan trend in contemporary Kashmiri writing—particularly in English—that victimises a community, demonising the other while valorising the self, Kaul subverts the binaries of good and evil, friend and enemy, self and other.” As exemplified in this selection, Kaul does not create reductive caricatures in the guise of characters, whether Muslim or Hindu. Moreover, neither the exodus, nor the events surrounding it, make up the sole focus of his narratives; he is not interested in the incidents themselves so much as the rootlessness and unbelonging they engendered. Tanveer Ajsi elaborates: “Not assuming the inclusive character of Kashmiri society, he excavated the strengths that bound it together, while also exposing the fault lines that lurked behind its cultural veneer.” As such, Kaul’s work can also be seen as a questioning of Kashmiriyat, the much-romanticised idea of communal harmony and religious syncretism in the Kashmir valley, which—despite its gradual erosion—still sees people swearing by its steadfastness.

That being said, Kaul’s depiction of stereotypes, microaggressions, and regular bigotry on the basis of caste and religion, among other things, are still very real. In “That Which We Cannot Speak Of”, he explores such interpersonal dynamics through what is explicitly said and what is left unsaid in the valley. The narrator’s relative, unable to find a blood relation to host his daughter’s wedding, accepts the offer of a Muslim colleague. The priest is not happy: “How can sacred wedding rituals like Kanyadan and Brahma Yagna be performed in a mlechha’s house? Would this be sanctioned by the Vedas and other holy books? . . . Give them half a chance and they’ll slaughter us all in an instant. I don’t know what is stopping them.” Similar divisions are explored in “The Mourners”, in which a body is being made ready for funeral. When a Muslim neighbour tries to assist, he is immediately dissuaded. One character claims, “Hey, mleccha! Don’t touch the bier, the corpse will be polluted.” Another is quick to add: “She’ll jump off the bier if she finds out a Muslim is carrying her corpse.”

These prejudices implicate not only cultural rituals but also daily life. “Summer” follows Poshkuj, who is spending some time with her younger son and his wife in Delhi—a place more appealing to her because of the religious makeup of its people, as opposed to Srinagar, where she lives with her elder son and his family: “Everything else be damned, at least there are no Muslims here. All around me are my own Hindu people.” Later, she is incredulous to find that the building she had been mistaking for a temple is actually the Pakistani embassy: “What kind of a fool does she take me for? . . . In Kashmir, despite all the Muslims around, no one speaks of Pakistan openly. So how can there be an office of Pakistan here, in Delhi, where only Hindus live?” When her son takes her to Chandni Chowk to show her around, she realises that it is not a Hindu-only city: “I wonder if they fear living in Delhi just as we fear living in Kashmir. But we haven’t been killed there, so why would they be attacked here? Still, how do you smother the fear in your heart?”

Her animosity towards Muslims is not Poshkuj’s only defining feature. She also holds a lot of internalised misogyny, revealed in her perception of her two daughters-in-law—especially the elder one, whom she calls a “shrew” and a “monster mother”. Sexism is present in other stories as well, and often it is women bringing other women down, more vociferously so than men. In “The Saint and the Witch”, Ram Joo and Sonmaal, his wife, discuss the death of a well-known man and his “ugly and unworthy” wife whom “he put up with without complaint.” Sonmaal is incredibly overzealous in airing her ‘faults’: “What a wife! Stupid and just plain awkward. . . She gave him no comfort. Now she’ll reap as she has sown. . . Even a bitch is preferable to a barren woman. . . It’s not just about her looks. She’s a monster.” This garden variety misogyny, albeit bitter, certainly adds verisimilitude.

But not all of Kaul’s stories are completely grounded in the real. In fact, a few of them are memorable precisely because they use surreal elements to showcase the failure of pedestrian language in articulating lived realities. “Tomorrow: A Never-Ending Story” follows Sulleh and Makhan, two friends and classmates across the sectarian divide, as they find themselves subsumed to the routine of home and school. All around them, the world keeps on moving ahead as tomorrows come and go. Meanwhile, they are both stuck in school: the same classes, the same homework, the same punishments. Right at the end, one asks the other: “Why didn’t we grow up?” The reply comes: “I don’t know. They say fools don’t grow up.” The story has more than a hint of Samuel Beckett, channelling the paralysing limbo and inaction that innervated Waiting for Godot.

A later story, “The Tongue and the Egg”, ventures even further into the realm of the unreal. Thugs have been tasked to collect—or rather confiscate—six million eggs from the masses so that the egg whites can be used to prepare a construction mixture, required for the building of a new mansion. In this world, the wealthy remove their own tongues, keeping them in their fridges for safekeeping and taking them out only when necessary. The protagonist is incensed and tries to understand the state of the land, but neither the holy man, who has taken on a year-long vow of silence, nor the wise man, more interested in debating the egg and the chicken question, have any answers. The strain of Beckett is now joined by one from Orwell: “There was silence all around. I debated whether I too should remain silent, but realised that between my friend and me, I alone had a voice. His tongue had been pulled from its roots, mine was still there. So how could I refrain from speaking?” Here too, life comes in slant.

Considerable effort has gone into making this book a reality; there were significant obstacles every step of the way. Kaul’s family did not possess any of his papers nor the actual manuscripts, as they were left behind in Kashmir amidst the migration’s immediacy. The magazines where his stories were originally published, as well as his books, were also hard to procure—either out of print or not available digitally. The four collections were finally located in the library of Kashmir University, in conditions that Raina describes as “less than ideal. They were in need of preservation. The ink on some pages had faded and entire sentences were sometimes erased.” A small group, made of Kaul’s contemporaries as well as younger students and writers, then helped select the stories that became a part of this English volume.

Raina also highlights how the project culminated from a truly collaborative process between a team of translators representing “a diversity of gender, age, experiences, and religious identity.” She explains: “My knowledge of Kaul, his particular milieu, and the various backstories was enhanced by my collaborators’ familiarity with Kashmir, its literary history and landscape, and Kaul’s place in it. . . We allowed each other to work on our separate drafts, but then, over two years of in-person and virtual meetings, interrogated initial assumptions and suggested alternatives that were sometimes accepted and sometimes discarded. . . We listened, debated, and challenged each other’s understanding of the works.” Gowhar Yaqoob also discusses this process with appreciation: “The conversations expanded the context of the stories. Listening to each other’s readings allowed us to follow the continuous and uninterrupted thoughts of the author, permitting a stronger sense of interaction with the stories that generated more diverse meanings in phrases, expressions, and clauses.”

The result of this tremendous endeavour is a collection that represents Kaul as a chronicler of his times, mapping memory and history. In delving into psyches and pedestrian realities, an enduring theme in his work is the uncertainty and ambiguity that dogs the lives of Kashmiri people. In the titular story, the characters are trapped for a night in a ramshackle rest house during a winter storm, after a major landslide had delayed their travels. Seeing that the narrator is uneasy, a fellow passenger tells him to treat it as an illusion, a temporary dream that will go away in the morning. He then ponders on the idea: “When we wake up tomorrow, these mountains will not exist, nor the rain, nor the wind, nor the biting cold. . . But it is a long time until morning. For now, it is night. For now, it is dark. For now, it is cold. In this darkness and this cold, I am alone.” This overwhelming feeling of an eternal, long night is perhaps common to all Kashmiris—both residents and the diaspora, Hindus and Muslims alike. However, it is not all doom and gloom for in this proverbial fire. True to Kaul’s dedication as a writer for his people, For Now, It Is Night also shines a light on their collective endurance, adaptability, and will to march on.

Areeb Ahmad is editor-at-large for India at Asymptote and books editor at Inklette Magazine. Most of his writing can be found on his bookstagram, a true labour of love. Their reviews and essays have appeared in Scroll, The Chakkar, The Federal, Hindustan Times, and elsewhere.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: