These days, many of the images we see from Palestine are ones of unbearable violence—a necessary example of what Roland Barthes called “the experiential order of proof”. However, despite the vital role of these photographs in bearing witness and documenting the ongoing atrocity, there is an equally essential need to elaborate this unidimensional representation with the social soul and experienced terrain of these historically rich territories, and to thus unite the psychically separate fields of the unthinkable and the daily.

As such, it is with great urgency that writers and scholars Margaret Olin and David Shulman have collaborated to produce The Bitter Landscapes of Palestine, a compilation of photographs and texts, to be published as part of the Critical Photography series by Intellect. In their brief introduction, they state only: “We will speak of what we have seen and heard directly and what we have experienced in our bodies.” From that dedication to perception, they illuminate the extent to which intersections of photojournalism and intimate speech can establish compassionate, mutual relationships between viewers and subjects, and how photographs and poetics can be used in ways that do not seek to control information, as in the mechanisms of tyranny, but that reassert their expressive, transformative function: impressing a fragment to open up interrogations into the whole; inducing the epiphany of recognition; and offering the potential of a unified political space.

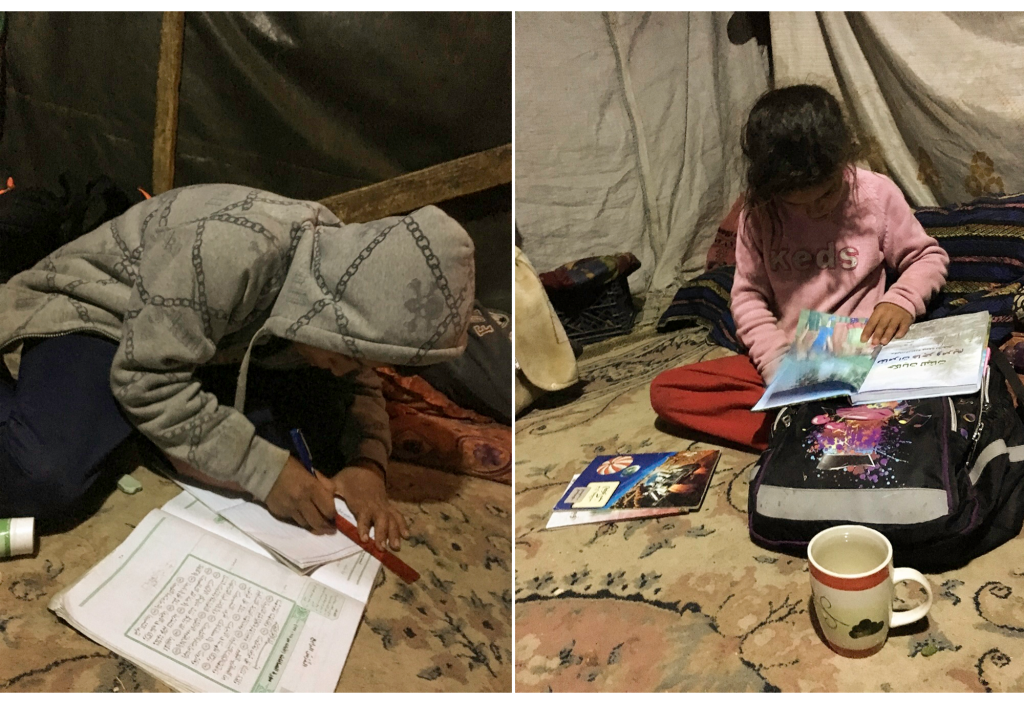

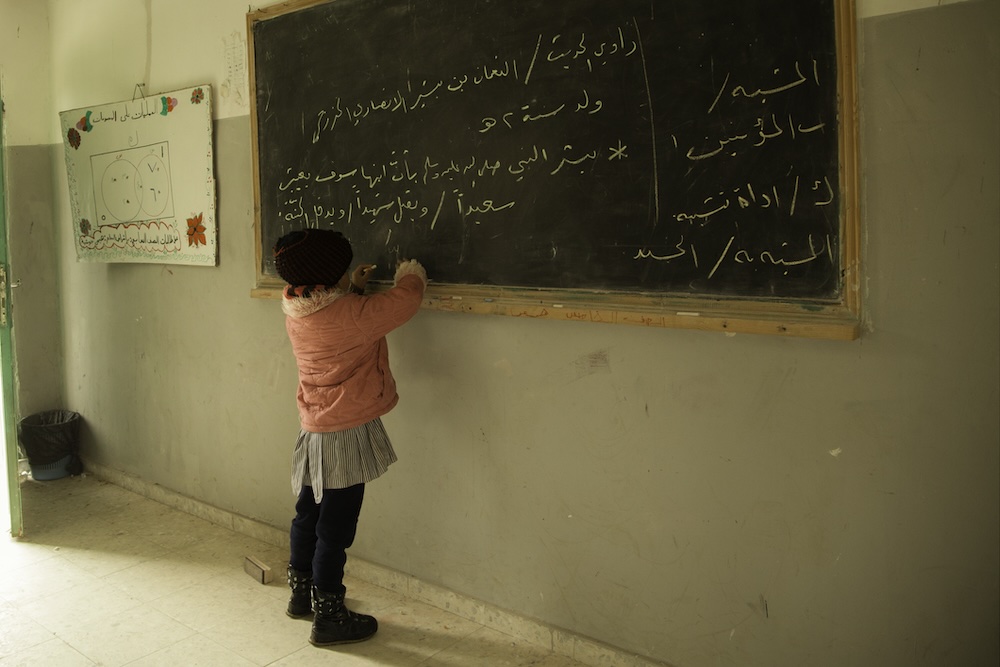

In the following excerpt, which consists of the book’s fifth chapter, titled “Arabic”, Olin and Shulman describe the sonic and interpersonal fabric of language under occupation, pairing the text with an array of images that portray communication’s various appearances: books, letters, conversations. The resulting interplay is evidence of how a single word—injustice—can grow and grow until it contains an entire country; how there is no scale for such grief, just as there is no true physicality for words, but still it is felt and carried, every day.

Susiya, March 2016

First, the music. It changes from place to place. The city Arabic of Jerusalem and Ramallah becomes gruffer, rougher, in the desert, where the guttural “q”—often pronounced only as a glottal stop, that is, a quick catching of the breath in the throat—turns into a “g.” The shepherds’ language flows seamlessly into the cries and whistles and grunts they use to speak to the sheep. At the same time, they sprinkle their sentences with the astonishing formulas of courtesy that come so naturally to the tongue: May Allah heal you, give you peace, bless your hands. We thank you, you have honored us. Welcome, you are our guests. Go in peace.

Wadi Sweid, July 2019

If one lives inside that language, some things become clear and necessary in a way that no translation can convey. Take, for example, the verb zalam—to wrong someone, to treat unfairly, to oppress—and its noun form, zulem, injustice. “ayishin fi hayaah kullayaat-ha zulem eb-zulem,” “We are living a life of oppression within oppression” (J. Elihay, The Olive Tree Dictionary, s.v.). It’s not only the Occupation that produces such sentences, though it’s a fertile ground for them. Deep in the fiber of the language is a notion of malicious hurt—often linked to other words, such as pride or honor, sharaf, or what is right, haqq. Zulem (the noun form) happens all the time; it is almost as if one were waiting for it, with an exquisite sensitivity to potential pain that radiates outward from the core being of the person. Seen from the other end, this is the unthinkable grief that comes when that inner self, so deeply hidden, is violated, ravaged, disregarded. At the heart of zulem is an unfairness that no human creature can understand or withstand.

It can happen any time, in everyday interactions, in love or friendship. It is something entirely tangible or sensual, felt not in the mind but in the pores of the skin and the invisible folds of the gut. But: The Occupation is a machine for manufacturing mass quantities of zulem. In a way, that is its true purpose. The settler or the soldier, carrying a gun, drives you off the land your father and grandfather and great-grandfather plowed and harvested, the land where they grazed their flocks. You feel the zulem-driven cry of that land inside you—the land that is a living part of yourself— and the violation can drive you mad. A thousand horses pulling your heart from your body with knives and ropes would hurt less than what the settler or the soldier is doing with words, a scrap of paper signed by the battalion officer, and a gun. All human beings may know this feeling, but in Arabic, it has an irreducible aspect of sacrality. Life itself is being abused, misused for the sake of cruelty, against the natural order of desert and rocks and trees and rain and sheep and the bread one bakes and the sun that rises and sets as an unerring witness to zulem.

Zanuta, March 2015

It’s different from political injustice or unfairness, it’s not a legal abstraction, it’s not even something in the mind, a mentalistic configuration made with words. Zulem can be healed with words and deeds, if they are truthfully felt and uttered, but the Occupation regularly, hourly, compounds zulem within zulem.

There are other, more innocent words that carry that same tangible force and texture: “Show me the breadth of your shoulders” (from behind—in other words, “Get lost.”) “Excuse me for mentioning it” (literally: “May Allah honor you”—ajallak.) Or the omnipresent ma‘alesh, “I hope I haven’t hurt you too much.” There is the everyday politesse and the simplicity of wonder: “I like that a lot,” ‘ajabni ktir. And always the appeal to the God who is very close, though sometimes not close enough; the God who lives in the throat or on the tongue and, dependably, in the density of sound.

Susiya, March 2016

The Bitter Landscapes of Palestine will be published by Intellect on Jun 14, 2024.

This piece is appearing as a part of the ongoing series, All Eyes on Palestine, in which we present writings and dialogues with insight on Palestinian literature and voices, and their singular value. We hear the Palestinian peoples, and we condemn the violation and deprivation of their human rights.

Margaret Olin, born Chicago, 1948, is Senior Lecturer Emerita, Yale University. She specializes in visual culture and theory, and is also a photographer active in the Israeli-Palestinian peace movement.

David Shulman, born Waterloo Iowa, 1949, is a Professor Emeritus, Hebrew University Jerusalem. He is scholar of South Asian language and literature, and veteran activist in the Israeli-Palestinian peace movement.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: