Where the Wind Calls Home, Syrian author Samar Yazbek’s latest novel to be translated into English, is a stunning offering of spirituality, memory, and all those implacable, liminal spaces wherein only the mind may venture. Written from the perspective of a young soldier as he lays dying from his wounds, Yazbek describes both the unthinkable wreckages of conflict and the translucent totems of faith with her singular musicality and vividity, tracing backwards through recollections and reveries to collage all the brute realities of civil war with the individuals whose rich internal lives pattern the battlefields.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

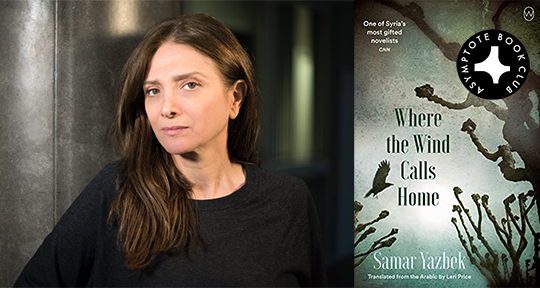

Where the Wind Calls Home by Samar Yazbek, translated from the Arabic by Leri Price, World Editions, 2024

There is an unforgettable moment in Adania Shibli’s Touch when the child narrator, through whose eyes the world arrives in intensities of colour and sensation, attempts to decipher words emanating from the TV. Amid the flotsam and jetsam of indistinct syllables, she finally makes out “Sabra and Shatila”. She thinks then not of the horrific massacre in Beirut but of the sabr cactus growing in her vicinity; the name, stripped out of the matrix of history, can only signify as something tangible, close at hand.

Such strategies of defamiliarisation came to mind while I was immersed in the free-floating atmospheres of Samar Yazbek’s Where the Wind Calls Home. Its oneiric rhythms, elegantly recreated in the English translation by Leri Price, mimic the roving consciousness of an adolescent soldier, known only as Ali. Forcibly conscripted into the frontlines of the Syrian Civil War, he survives an enemy attack in the Latakia mountains only to hover on the edge of death. As he struggles to regain a feeling of where his injured, possibly dismembered body might begin and end, his mind takes flight; memories of childhood creep back into him. Time on the narrative surface runs the course of a single day, blue sky shading into a “raw and tender” moon. Beneath reality seethes the inexpressible current of remembrance, obeying its own laws of sequence and cadence.

Yazbek is more interested in the sensuous immediacies of embodiment than in the airy abstractions of power. Her previous offering, Planet of Clay—a finalist for the 2021 National Book Awards, also translated by Price—inhabited the perspective of a mute girl, similarly caught starkly within the crossfires on the Civil War. Against its barbarities, she seeks a sanctuary in crayoned drawings and imagined planets. Even in Yazbek’s non-fictional accounts of revolutionary betrayal, ranging from the diaristic to the journalistic, she retains a similar sensibility: “Oh spinning world, if my little heart, as small as a lump of coal, is wider than your borders, I know how narrow you are!”

Where the Wind Calls Home sidesteps the instant of carnage and cruelty, focusing instead on its shattered aftermath—the sheer disorientation of a self’s fundamental coordinates. When we first meet Ali, awakening into a haze of delirium, the horizon of his awareness stretches no further than the leaf that has fallen and covered his face. Time, space, identity are all scrambled. Numbed to his other senses, Ali clings on to existence through the faculty of sight; he literally perceives himself as a disembodied, aerial eye. Like the very narrative apparatus through which we apprehend his brokenness, his self-observation shuttles between intense identification and estrangement.

Within this opening is cleverly embedded a fractal premonition of everything to come. Ali vacillates between animation and immobility as he strains to recover a hold on personhood and place. Pain continually returns him to flesh and sinew: “he regained his knowledge of himself, a little more with each repetition, as if he were climbing a ladder, going down new pathways, opening small windows.” Through each of the following chapters, we observe him tentatively testing his wholeness, sometimes hallucinating a nightmarish vision of severed limbs dancing and circumambulating a nearby tree, sometimes imagining his body grotesquely exploded into “motes of dust”.

Though war operates as the novel’s inevitable fulcrum, Where the Wind Calls Home carefully evokes the density of an interior life that exists prior to, and beyond, the machinations of sectarian violence. Ali’s is a soul keyed to the unearthly; he finds a dwelling in dreams and in the language of trees, and through his reveries, Yazbek indulges in protracted paeans to the infinite hues and nuances of nature, the “carnival of interwoven colours” permeating each cloud. Long paragraphs, often running uninterrupted for several pages, unfurl Ali’s longing for oneness with the wide, inhuman world:

He would watch the light and he knew what it meant when branches and leaves played with light. In his arzal he would spend hours watching a magical world of colour games. Suns large, small, and all sizes in between, would waver, appear, disappear, leaping high and tumbling down, different at each hour of the light’s movement. The sun and moon alternated in the heavens, where light and darkness peeled away, and each of them bobbed and waved among the tree branches like apples.

He might know “what it meant”, and yet this meaning, in its sublimity, seems bound to opacity, beyond reach of the human language so anathema to Ali.

Spirituality, for the believer, brooks no speech. Ali ignores the buzzing of planes overhead and the petty squabbling of villagers; he resists his parents’ bid to enrol him in school, preferring the company of beasts. Invocations of government ring no bell: “Even with the passage of years, Ali had failed to learn the shape of this state that he had never seen, although so many spoke in its name.” No wonder that he makes kin with those on the fringes of society: the red-haired outcast Humayrouna, who names Ali “son of the tree” at the maqam (holy shrine); the old sheikh from whom Ali learns religion; his deceased aunt, remembered for throwing herself off the mountain, believing that she had sprouted wings.

In this bisection of reality and the world of the soul, politics only billows in and out of the novel every now and then, like a curtain in a slight wind, manifesting in peripheral glimpses. Ali’s favourite tree turns out to have sheltered revolutionaries on the run from the French, prior to Syria’s independence. Humayrouna, claiming to have lived a hundred years, links the scent of tobacco to “the smell of oppression”, telling of an uprising by impoverished farmers against the Ottomans. The real-life tenets of spirituality, too, are only an undercurrent. Though Where the Wind Calls Home is billed as one that examines the “secrets of the Alawite faith”, the words ‘Alawi’ or ‘Alawite’ never appear. Yet, those more plugged into the intricacies of this heterodox sect might read into the allusions to reincarnation and Eid al-Ghadir. Yazbek’s broader gesture is perhaps to the irrelevance of such sectarian designations to the textures of the everyday. She writes from within such a totalising frame, and will not care to exoticise faith, or render it cheaply legible.

Closer to our contemporaneity, Ali witnesses—often wide-eyed—the ascendance of a class of new sheikhs, who insist on monopolising the signification of martyrdom. Funerals are rudely interrupted for “the President and the nation!” The President, ominously capitalised, is of course Hafez al-Assad, himself an Alawite. Acutely conscious of his minority status, he had proceeded with great political acumen when he rose to power in the seventies. Rather than accentuating Alawite alterity, he rallied the population around a secular ideal of the Syrian nation. But behind the scenes, he created a clannish Alawite elite. The reverberating costs of his dictatorial consolidation, all too predictable, are documented in Yazbek’s text. “Traitors” are exiled, villagers mysteriously disappeared, farmers’ land seized in an uncanny echo of history.

Alert readers might intimate—across these cross-cutting, dimly traced subplots—the story of something like Syria’s jagged modernity. Where the Wind Calls Home probes and traverses, with great astuteness, the distance between orders of faith and nation, as well as the violence that might spring from their mutual collapse. Promptly succeeded by his son Bashar (who too remains unnamed by Yazbek) after his demise, Hafez al-Assad’s portrait is framed alongside those of the virtuous saints in the maqam. Ali, in his characteristic innocence, wonders “how the President had died then come alive again”. There might be something cyclical in that , a continuity that Ali—attuned as he is to the slowness of cosmic time—seems poised to intuit.

The allegorical gravity of Ali’s name could be lost on Anglophone audiences, but it is worth noting that ‘Alawiyya’ means ‘follower of Ali’. His disfigurement, with each twist of pain, narrates the plight of a country being killed “from within”. That might be the artful gambit of the novel, through its manipulations of proportion. Ali’s elemental fixations extend beyond the metaphysical to implicate the problem of politics. While American and Israeli airstrikes on Syria and Iraq intensify today, we have to wonder: how might we assemble a history of the present, as it is lived and suffered? Edging closer to the book’s already foregone conclusion—Ali’s fateful conscription—we sense these scales chafing against one another.

And they might come together with most force in the indeterminacy of Yazbek’s title, Maqam al-Rih. It refers, most directly, to the name of Ali’s maqam. Built on the mountain’s peak and embraced by trees, the shrine gives Ali the feeling of a “secret that was his alone”. The word ‘maqam’, however, is difficult to translate across its semantic richness in Arabic. It can mean ‘place’, ‘station’, ‘ranking’; its valences can be religious, political, musical. That Leri Price, the translator, opted for the relative pronoun ‘where’ feels like a bit of a marvel. In English, Where the Wind Calls Home reads like a stranded clause, pointing to something that has come before, or something that remains to be spelled out. It is intimate, not yet tethered to a form, like a breath of life—a secret that is the book’s alone.

Author photo by Astrid di Crollalanza

Alex Tan is Assistant Managing Editor at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: