In the 2023 documentary Translating Ulysses, Turkish filmmakers Aylin Kuyel and Fırat Yücel chronicle the painstaking efforts of poet and translator Kawa Nemir in rendering James Joyce’s “untranslatable” tome into Kurdish. This herculean task, which may seem rooted in the desire of any lover of literature to share a classic text in their native language, is in fact a tremendous act of activism for the Kurdish language, which has long been suppressed by Turkish nationalist policies, as well as a testament to the written text as a living, ever-changing discourse. Through close observation and innovative cinematic technique, Kuryel and Yücel paint a moving, profound portrait composed of the destructive language politics in contemporary Turkey; the tenuous, confounding journey of the translator; and literature as archive. What results is a film that is not only a document of Nemir’s epic journey through the Joycean labyrinth, but a remarkable, intricate tracing of how the vast history and collective memory of language can find a home in a story, or in a mind.

Xiao Yue Shan (XYS): Aylin, the relationships between images and their communication of ideology has been a continuous subject in your work as a filmmaker and thinker. In this film, however, it is not the image which takes centre stage, but a text; how has your conception of visual dialectics transferred into the consideration of language as a social and ideological construct? Has making this film changed the way either of you think about the role language plays, or the way its public usage interacts with discrete individuals?

Aylin Kuryel (AK): One of the central questions that haunted us while making this film was indeed how to ‘translate’ the process of translating a text into images, how to make both Ulysses itself and Kawa’s translation of Ulysses speak in images. This is probably why we ended up structuring the documentary in chapters, like a book, with each chapter focusing on a different aspect of the process of translation. We wanted to approach the film as a text itself, making references to Ulysses, and edit it in a way that would allow the images to be ‘read’ in multiple ways.

We had the ‘speaking soap’ of Joyce in our mind while focusing on objects that surround Kawa during his translation process, the colours of Ulysses’s chapters while playing with the colours of the film, and so on. The language of the film needs to reflect—or at least allude to—the subject it follows. Therefore, apart from the references to Ulysses, we also wanted to use found footage (official propaganda material or visuals of Kurdish resistance, taken from Youtube and social media). A documentary that attempts to touch upon a long-lasting collective resistance (in this case, against the oppression of the Kurdish language) can consist of a collective of images too, captured in different periods, by different people and organizations, for different purposes.

XYS: Yes, there’s a substantial amount of found footage used in the film—and this form of collaging can also be seen as a type of translation: a translation of contexts. What was your thought process in stitching together the various contents, and in your opinion, how does this speak to the way that documentary filmmaking directs and controls the interpretation of reality?

Fırat Yücel (FY): The logic of traditional documentary making rests on a colonial aspiration: to go somewhere and reflect and uncover its “hidden, eccentric reality”. But in fact, you don’t need to travel to reflect the injustice that permeates every inch of the nation-state. You don’t have to go to places—and the reality is in fact not hidden! It’s everywhere you look. The logic of collage enables you to see this. For example, the footage of Kawa in the cooking show—we found that footage on Youtube. Many people who watched the documentary said to us that they didn’t know that there were shows like that, cookery programmes filmed in Kurdish. Many people who live in Turkey don’t know about the fact that the Kurdish people have their own channels, where they talk about food, or James Joyce, or Cegerxwîn! They only hear about these channels when they are shut down by the state. Hence, just by incorporating such footage in a documentary on translation, one can reorder reality. That’s the power of collage. Just by reordering things, you can show people that there are different realities, different popular cultures and ways of interacting. The Kurdish people have their own cooking shows, and what’s more, contrary to similar shows in Turkish channels, they talk about food, politics, and literature at the same time. So, in fact, in that footage, Kawa is making a collage—he’s mixing pudding and Cegerxwîn! And we are expanding this logic of collage by putting this scene in a documentary on Ulysses. The collage techniques of Joyce, Kawa, and the documentary blend into one and other, get empowered by one and other.

AK: This is also true with the Covid-19 footage: World Health Organization is broadcasting a video in Kurdish for the first time in history, and Kawa is asking people to “stay home” in Kurdish. By using the technique of collage, we are creating a reminder that there are many people in this world who will only stay home when they are asked in Kurdish. Hence, in fact, the collage of languages and the collage of archival/found footage have a similar function in the film; they mirror each other. After all, we are dealing with a long-lasting collective history of struggle, and a film that attempts to give a cross-section of such a process can only expand through a collaboration of images/sounds recorded in different contexts.

XYS: One of the most magical things about this film is its depiction of how someone can work at the frontlines of language—rescuing it, broadening it, or allowing it to reach new depths. Kawa acknowledges and takes on this responsibility of carrying Kurdish—and specifically Kurmanji—into the future; could you tell us a little about how the making of this film evolved with the ongoing tensions between languages in Turkey?

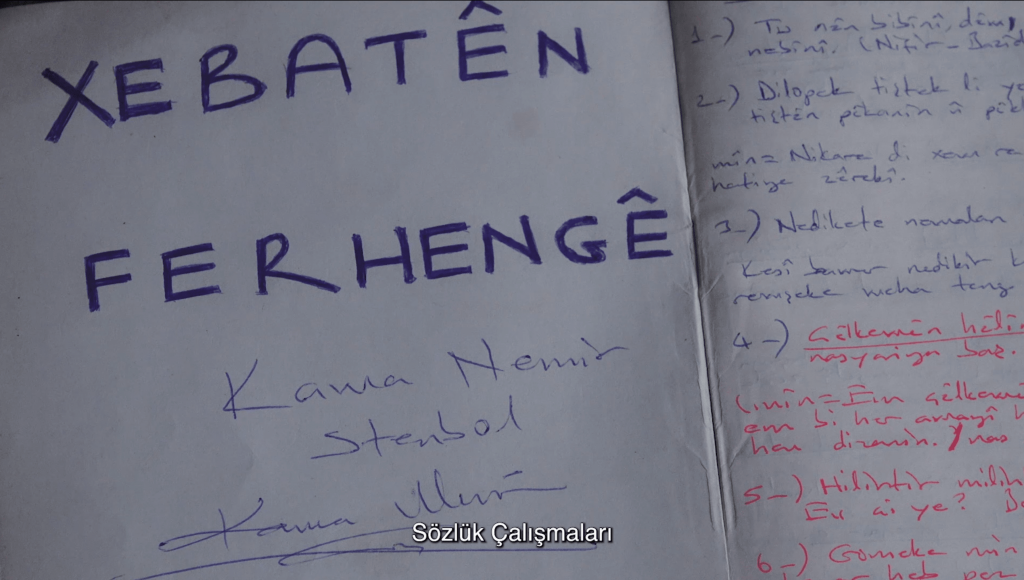

AK: In one of our first conversations, Kawa framed his translation of Ulysses into Kurdish as a “revenge story”: a revenge that must be taken against the Turkish state, where there is a long history of assimilationist state policies which oppress the Kurdish language—the mother tongue of millions of people who live in Turkey. Our political affiliation made it easier to form a friendship with Kawa, which in turn made it possible to follow this long and lonely process of translating one of the monumental literary pieces of modernism into an oppressed language. Following Kawa’s journey of translating Joyce’s Ulysses—one of the markers of the Western canon—into Kurdish, a language that is systematically censored by nationalist policies and daily racist attacks, was a way of exploring the act of translation as part of ongoing anti-nationalist and anti-colonialist struggles. Joyce, in Kawa’s words, joined the ranks to “save people from understanding the world in Turkish,” and it was an exciting way to delve into the relationship between language and ideology.

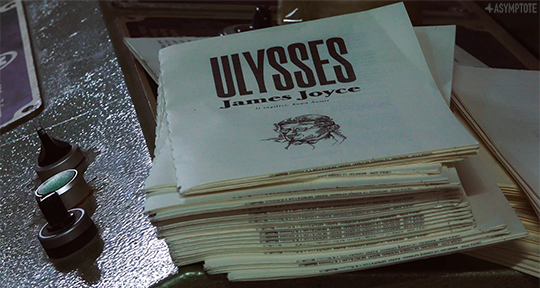

Ulysses takes place in one day; it is about the events and encounters in several characters’ lives in Dublin on June 16, 1904. In the anatomy of a single day, a Thursday, spread over seven hundred-odd pages, there is an incredible compendium of daily life. It consists of newspaper clippings, advertisements, political discussions in bar corners, the price breakdown of objects, etc. At the same time, it is a book that “imitates” different genres of British and Irish literature, jumping from one style to another, distorting and reconstructing as it intertwines them. At times it turns into a play, at other times into a cheap romance novel; in one part it tries to construct a language that aims to approach music, while in another it takes on stream of consciousness almost without punctuation, from Molly’s own mouth. Therefore, Ulysses opens up an incredible space for transferring words, phrases, and linguistic forms that are used daily in Kurdish, but have not yet been transferred to white paper.

Ulysses is part of the canon, yet it also has the reputation of being “the most known but least read novel”. It’s full of details about everyday life in 1904 Dublin, thousands of references to Irish folk songs and, at times, goes into a cryptic language that is very difficult to decipher. But this is in fact bliss for the Kurdish reader; thanks to this vastness of Ulysses, they will find Kurdish words in this translation that they haven’t heard for a long time, waiting somewhere in their collective memory or even their subconscious—words that their grandparents used when they were children, or even words that they haven’t heard of. Just like Ulysses itself, this translation is an encyclopaedia of Kurdish language; an encyclopaedia that reveals how rich language actually is and, in direct proportion, the extent of the colonial violence of the Turkish state apparatus against this language.

Perhaps this is what makes the translation of Ulysses a gift for the Kurdish language and its readers; it allows the archiving of this linguistic heritage, and also explores and pushes the limits of existing language. As Joyce pushed the limits of the English language, Kawa had to do the same in Kurdish.

On the other hand, one of the main axes of Ulysses is Ireland’s relationship with the British: the history of colonialism and the struggle for independence. Joyce is simultaneously an anti-colonialist and distant from the nationalist tone of the struggle for independence, and these debates are very much present in the book. Translating this text in another colonial geography today gives it a different political and symbolic meaning, broadening the ever-expanding universes of both Ulysses and the Kurdish language/literature.

XYS: Usually, differences in language are represented as an obstacle—a language “barrier”; but in the case of a repressed language such as Kurdish, this difference is essential to establishing an autonomy. As translation is very much a concept that seeks to overcome difference, it can lead to both the mutual understanding between two disparate cultures, and the colonial practice of assimilation and uniformity. What do you think is the role of translation in our reality, which is so prone to division, but also so vulnerable to abuses of power?

FY: I think translation is more about revealing differences rather than diminishing them. For example, there’s an episode called “Talking like TRT” in the film. It’s an idiom invented and used by the Kurdish people to denote the repetitiveness of the Turkish state Radio-TV channel (TRT), and no such idiom or phrase exists in Turkish language. It shows us that under the same nation-state, there are differences in experience which can only be revealed through translation. For the Turkish people (or let’s say the people who were taught to be Turkish), the mainstreaming of the television in the 70s seemed like a technological revolution. But for the Kurdish people, it was a whole different reality. As if in a parallel universe, they gazed at this rectangular machine and the talking heads inside its frame, without understanding the spoken words. The ones who knew Turkish could understand what was being told, but most of them couldn’t relate to it. The machine was speaking the language of colonialism: the almighty state, agricultural enrichment, economic growth, militaristic achievements of the Turkish army, etc. It was so far removed from their own experience in Kurdish towns and villages.

Hence in the 90s, Kurdish people searched for dish antennas and obtained satellites receiving Kurdish channels (which were broadcasting from different countries of Kurdistan region and Europe). Those became the source of reality for them, and in the parallel universe, TRT was repeating the same thing during the huge struggle for Kurdish autonomy: “Terrorists neutralized.”

Translation can help uncover such idioms and the histories behind them: the histories of the people, the languages they speak, the words that have been forcefully erased by the Turkish nation-state. The obligation to speak and write in Turkish was introduced to prevent the telling of these histories. Translation as we understand it is not a tool to bring cultures together, but rather a humble literary weapon in the hands of the people to reverse this process of assimilation, to let them say: the reality was and is different for us.

XYS: Aylin, you have previously written on how when art and activism intersect, the “reification” of creativity can lead to the neglect of the political or social struggle, quoting from Stevphen Shukaitis in stating that aesthetics should not “become separated from the body of social movement or congealed into a specialist role within it”. How do all of you see your work—these indisputably creative, specialist acts of filmmaking and writing—as meeting the social movements in Turkey?

AK: Neither literature nor filmmaking have a privileged political role; in this sense, both Kawa’s translation of Ulysses and our film, which attempts to capture this process, can only be seen as part of a larger and ongoing struggle against the oppression of peoples and languages. The conditions that led Kawa to migrate to Amsterdam are clearly still in place today; war policies continue, trustees are appointed to municipalities in the Kurdish region, Kurdish parties are systematically shut down, websites of publishing houses that publish books in Kurdish are blocked, and so on. Kurdish, as we have repeatedly seen, is a language which, if spoken outside the borders authorized by the state, can cost lives.

Although Translating Ulysses puts the translation of Ulysses into Kurdish at the center, it also tries to make a map of this struggle—albeit in a limited way. This is why we interrupt the narrative with newspaper clippings, news, and found footage; we were trying to emphasise the infrastructural reality in which the translation takes place.

Related to this, one of the questions that haunts the film is what home is: is it a city, an existing or imaginary country, is it a political struggle that one feels part of, is it language—as in one of the chapter titles: “There is a home there, but where is it?” Another question also arises, following this one: can we make a film about translating Ulysses into Kurdish without talking about the political situation unfolding in Turkey, without mentioning the suffocating bureaucratic obstacles and the housing crisis in Amsterdam, or the rising right-wing sentiments that blame all problems on immigrants? Hence, both translation and filmmaking emerge within and are shaped by larger political struggles, rather than being separate creative acts.

XYS: Much of the psychic violence of colonialism can occur in the removal of language from the colonised, which makes them unintelligible to themselves. By bringing the language and the story of Ulysses to the Kurdish language, do you think that there will be something in the Kurdish condition of being that will be clarified? Do you think that the Kurdish edition of Ulysses will emit a new meaning?

FY: I think it will shake things; it already has shaken things. It showed that Kurdish is not a language that acts only with urgency, only with the reflex of self-preservation—that Kurdish can also be opened to the avant-garde, that it is a language resilient enough to find time and energy to open itself to the avant-garde, amidst all the atrocities and wars.

XYS: How did you two consider the depiction of translating—arguably a very private, concealed activity—in the medium of film, which always holds an element of performance?

FY: We at times thought it was impossible to reflect this visually. The image of this one person thinking, contemplating, solving puzzles etc. is in fact very superficial and banal; it doesn’t reflect the complexity of reality. Translation is a social and political process which refers to collective memory, and we thought it has to stay like that. When you show someone sitting at the desk translating a particular sentence from a particular novel, you don’t actually reveal the reality, you are shadowing it, because that sentence is not actually translated in that instance; that sentence has been translated through time and social interactions, which this image cannot capture.

Therefore, it was much more important for us to show Kawa saying that “these dictionaries are not enough”, that he has to “go hunting for words and idioms”, rather than trying to capture him “while translating”. It would also have been also a very gender-specific image of the translator, and we wanted to avoid that. We wanted to reflect his hesitations (the “not enough” moments) rather than his confidence. Instead of trying to capture the activity of literary translation itself, we wanted to show him translating in daily life, referring to a Kurdish idiom and explaining it to us, or switching endlessly between languages: the daily act of translation. One thing we couldn’t do is to reflect the lingual debates between Kawa and his fellow literati. We wanted that to be in the picture, but the pandemic prevented us reflecting on such sociability. It was mostly “us and Kawa” in the shootings.

AK: In addition, there is also the fact that translation is an “unfinished business”. Just like how translation takes place over time and through countless encounters and social interactions, some of its instances are never fully told, the translated text keeps circulating and acquiring new meanings as it is being read. So, it was also a question for us, how to reflect this unfinished business and how to “finish” the film. We decided not to avoid the question; hence, the documentary includes the question of how it should finish, directed to the people who are involved in its making.

XYS: There is some debate about how the film should end—whether to show the finished translation, or to leave it to imagination. The final section of is titled “Paper”, bringing the whole thing back to a solid, material fact, and what draws the film to a close is a scene of the book being printed and bound. It brings to mind an eternal debate of the arts: what matters more, the process or the product? What do you think?

AK: In our contemporary context, cultural products become commodities by mystifying their production processes and their “productness”. Self-reflexive gestures don’t necessarily break away with this mechanism. In our work, including this documentary, we tried not to avoid making references to the process of making the film—for instance by including “poor images” if we didn’t have better ones, or including our own voices, hesitations, questions in the film. We also wished to convey the sense of materiality of what is being talked about. Ending with the “Paper” chapter—the tactility of the book—was a way of moving away from what a traditional “portrait documentary” would demand. We leave the main character behind and following the book itself as an entity: the afterlife of translation. The book is both the “final product” and the beginning of a new process; it will start circulating, being read and discussed, and leave traces in the world.

FY: We can say that we tried to escape from the duality of this question by integrating the process into the film, yet we chose to end the film with showing the “final product”. There are certain reasons behind this choice: First of all, there’s an ongoing political fight for the visibility of Kurdish language. The politics of the Kurdish language relies on visibility, and is empowered by visibility. For example, today in Ireland, signs are bilingual. In Dublin, most of the people speak English, but you can see Irish everywhere. Yet in Amed, the city which is regarded by Kurdish people as the capital of Kurdistan, the opposite is true; most of the people know and speak Kurdish, but the signs are almost all in Turkish (except the municipality signs, the state was forced to back down on that issue). This difference is of course related to having or not having achieved state status. But the demographic and linguistic reality of the Kurdish region is undeniable, no matter what status it has.

Secondly, Kurdish is regarded as an oral language, a verbal language rather than a written language. It’s true that many people who know Kurdish can’t read it, and there’s a struggle to establish the language as a written language.

Mainly because of these two reasons, to show the materiality of the translation of Ulysses on paper was very important for us. It’s like saying: “well, you degraded this language, you called it an unknown language, as non-existent, or at times as a language that only exists orally, well there you go—Ulysses, the masterpiece of avant-garde modernism, on paper now.” Hence the print house scene also captures the transition of a language from verbal to written, and it is indeed something to celebrate! In this case, the product had to be caressed.

Aylin Kuryel is an academic and independent filmmaker. Currently she works as an Assistant Professor at the Literary and Cultural Analysis department at the University of Amsterdam. She is the co-editor of Cultural Activism: Practices, Dilemmas and Possibilities (Rodopi, 2010), Resistance and Aesthetics in the Age of Global Uprisings (Küresel Ayaklanmalar Çağında Direniş ve Estetik, Iletisim Press, 2015), Being Jewish in Turkey: A Dictionary of Experiences (Türkiye’de Yahudi Olmak: Bir Deneyim Sözlüğü, Iletisim Press, 2017), Essays on Boredom (Sıkıntı Üzerine Denemeler, 2020, Iletisim Press) and Utanca Bakmak (Looking at Shame, Cogito, 2023). Among her documentaries are Translating Ulysses (2023), A Defense (2021), CemileSezgin (2020), The Balcony and Our Dreams (2020), Heads and Tails (2018), and Welcome Lenin (2016).

Fırat Yücel is a film critic and a filmmaker. He co-founded Altyazı Monthly Cinema Magazine in 2001, and worked as the magazine’s editor in chief for more than a decade. He’s currently the editor of Altyazı Fasikül: Free Cinema, focusing on freedom of expression. As a filmmaker, he co-directed Only Blockbusters Left Alive (2016), and worked as the co-editor of the documentaries Welcome Lenin and Audience Emancipated in 2016. He co-directed the documentaries Heads and Tails (2019) and Translating Ulysses (2023) with Aylin Kuryel. With the duo-collective they formed, the Image Acts, Yücel and Kuryel produced the desktop documentary March 8, 2020: A Memoir in 2023. Yücel teaches seminars on topics such as Counter Cinema and Third Cinema, and gives film editing workshops on working with found/archival footage and other forms of documentary making (video-activism, collage, video-essay, desktop cinema, etc.). He’s a fellow at BAK (basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht) Fellowship for Situated Practice 2023/2024.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet, translator, and editor. shellyshan.com.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: