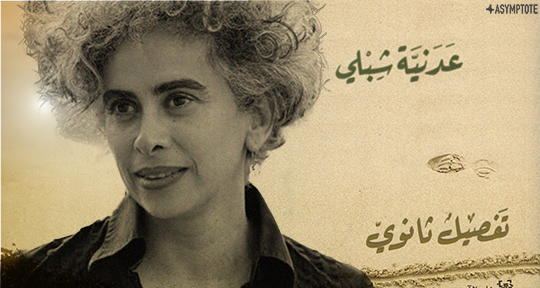

After the shameful decision to cancel Palestinian writer Adania Shibli’s LiBeraturpreis award ceremony at the 2023 Frankfurt Book Fair, everyone in the Global North flocked to read Minor Detail (translated into English by Elisabeth Jaquette), as thousands of writers, intellectuals, editors, and others in the literary ecosystem rightly condemned the cancellation. It was a symptom not only of Europe’s routine silencing of Palestinian voices but, more perniciously, of Germany’s particular brand of virulent anti-antisemitism, its Holocaust memory culture metastasised into a total interdiction on critiques of Israel.

Adania Shibli cites Samira Azzam—a writer whose seemingly unthreatening short stories describing everyday life in Palestine managed to pass the censorship bureau’s checks—as a formative influence. Azzam “contributed to shaping my consciousness regarding Palestine as no other text I have ever read has done”, Shibli writes, for it cultivated in her “a deep yearning for all that had been, including the normal, the banal, and the tragic”. For many of us, grappling with what solidarity and hope can mean in the light of Israel’s ongoing genocidal violence against Gaza, Minor Detail might be such an essential touchstone. How might we (re)read Shibli’s work today, not only as a prescient source of information about Palestine but also as a text that theorises and maps its own aesthetic possibility? With what voice does it continue to address us, reverberating through silence and the distortions of language?

One day, a splotch of black ink bloomed on my well-thumbed copy of Adania Shibli’s Minor Detail. I didn’t know where it came from. The blemish, to my consternation, appeared in the light-grey region of the cover, which depicts an undulating terrain. Misted waves, perhaps, or the volatile sands of a desert. Obsessed with keeping my books as pristine as possible, I took an alcohol swab and wiped the black dot right off.

The smudge was dispatched as swiftly as it had arrived. Days later, I noticed the alcohol had also dissolved the matte surface of the cover where I had rubbed it. A tiny glossy archipelago emerged, its lustre and its jagged edges visible only at an angle, under the light.

Now the sheen reproaches me for thinking I could make something disappear with no trace.

*

Desert / الصحراء

I want to juxtapose without asserting equivalence; the unnamed Israeli military commander in Minor Detail, too, believes in the seamlessness of disappearance. In the novel’s first half, he helms a Zionist platoon in a mission to conquer the Negev desert. This ruthless assertion of sovereignty takes place in 1949, a year after the traumatic Nakba dispossessed most Palestinians of their homeland. It is also a rearguard response to Egypt’s invasion of an Israeli kibbutz a year prior.

Charged with purging the land of “infiltrators”, the Zionist soldiers massacre a band of Arabs. They capture a Bedouin girl, humiliating, gang-raping, and murdering her. The horror of these bloodthirsty actions is continually evaded: “Then came the sound of heavy gunfire.” The narrative camera, as it were, turns its back on the moment of life’s desecration. Landscape itself seems to consent to these crimes. The desert, an aggressive mouth, collaborates in the erasure of evidence, each occasion with a different attitude: “languidly”, “greedily”, “steadily”, the sand sucks blood, moisture, substance into its depths.

I think of photographer Fazal Sheikh’s series Desert Bloom, in which aerial images of marks and imprints in the Negev reveal demolished homesteads and ruined Bedouin villages, a testimony to the Zionist extraction and contamination of the desert beneath a greenwashed veneer. As in Minor Detail, the distance from on high co-opts an Israeli optics of surveillance. With some of these pictures, it is not always easy to fathom the scale at which one looks. Yet the lines and contours, like cicatrices wandering along the length of a body, like scratches of an intractable code, call out to be read. The scene of a crime was how Walter Benjamin described Eugène Atget’s photographs of vacated Parisian streets. Deserted as Sheikh’s Negev might seem, it regurgitates the same evidence it had once devoured.

*

Camel / الجمل

For whom is the landscape legible in the time that remains, in the ongoing present of dispossession that Palestinians inhabit, and, especially now, against the genocidal horrors that the Israeli regime is inflicting on Gaza’s population with impunity? A crude bifurcation: if Minor Detail’s first half is obsessed with vanishing, the latter section wonders about the traces that return. Set in something like present-day Ramallah, a Palestinian woman becomes manically fixated on unearthing the truth of the Bedouin girl’s murder.

What preoccupies her is not the brutality of the deed; she laconically suggests that such incidents are standard fare in Palestine. Instead, reading of the crime in the news, she latches onto the eponymous ‘minor detail’ that it happened on the same date as her birthday. “There may in fact be nothing more important than this little detail, if one wants to arrive at the complete truth”, she affirms. If not for the uncanny temporal coincidence, she might not bat an eyelid.

Her detective quest unfurls into a reckless road trip, thwarted at each turn by a welter of checkpoints and inspections: the securitisation measures that partitioned the West Bank in the wake of the disastrous 1993 Oslo Accords. Though aware of her bodily vulnerability, the narrator undertakes an unremitting—but unavailing—journey through Israeli archives. These institutions tell triumphalist stories of Israel’s founding, revelling in their own machismo.

It is against this grandiose self-mythologisation, then, that the novel elaborates what we might call a philosophy, or an ethics, of the minor detail. The narrator adduces the fable of three brothers encountering a man in search of his lost camel in the desert. The trio describe the creature with impeccable precision, yet each claims that he had never seen it in the flesh. Brought before a court of law, they then enumerate the “smallest and simplest details” left behind by the camel in the desert: its uneven tracks, spilled drops of oil and wine, a tuft of hair. Fadwa Tuqan’s lines come to mind: “our land has a throbbing heart”, and “keeps the secrets / of hills and wombs”.

The camel, missing and bound to the finitude of its embodiment, could nonetheless be conjured as a composite of its idiosyncrasies. It left behind contingent remnants, identified collectively after the fact as irreducible bodily signatures. Refracted through the prism of this parable, Minor Detail hints at the desert’s caprices, its elusive legibility, its geologic cycles of concealment and recovery. Unlike that to which the Zionists hope to lay claim, the desert here is an archive possessed of its own music—a text that not everyone can, or will care to, decipher.

*

Fly / الذبابة

Driving through the altered landscape, the narrator of Minor Detail notes that the Israeli regime’s systematic demolition and rebuilding “reassert the absence of anything Palestinian”. She discerns little details, nonetheless, “furtively hinting at a presence”: unremarkable quotidian flashes like a clothesline and a solitary thorn acacia tree. Earlier, the narrator had professed to “see the fly shit on a painting and not the painting itself”. Now it manifests in a recycled image: “After a disappearance, that’s when the fly returns to hover over the painting”.

The camel never did reappear, but here the fly shows up, circling over its excreta. Might this be an emblem for Palestinian survival, its inconspicuousness to the settler-colonial eye enabling it to escape extinction? The minor, in order to persist, must gather to itself an agile, enigmatic opacity. It is furtive, like a thief: “a presence” not yet given to definition.

The Arabic word for “absence”, al-ghiyab, shares a root with the Islamic topos of al-ghayb, or the unseen—the nonmanifest realm, imperceptible but ontologically real. Enfolded into a theological register, Palestinian absence is resignified as indiscernible but extant, awaiting moments of partial revelation. I am put in mind of Georges Didi-Huberman’s fireflies, clandestine glimmers amid the tenebrous depths of fascism, offering themselves as a “passing, fragile pulse of light”, “an intermittent dash”. He reminds us: “To understand fireflies, we must see them in the present of their survival.”

Al-ghayb, where that which exists may lie in the unseen, signals to us one way of reading Minor Detail in its crystalline patterning. Shibli crafted it so intricately (it took her twelve years to complete) that nearly every image, every gesture, has an analogue in the book’s other half. I imagine an index charting out these recurrences: the mirage, the whipping wind, the thorn acacia and terebinth, the clouds of dust, the stench of gasoline, the intense shivering, the tripping and falling. Most of these are evanescent sensory provocations, but, by some inexplicable force of necessity, they linger through the decades. They suture the novel’s temporal gap.

None of this is apparent to the Palestinian narrator; she notices the thorn acacia tree but she is trapped within the constraints of her epoch. If a first reading leads us into a false sense of identification with the narrator, that closeness will likely fracture, severed under the weight of multiple rereadings. At the point that these motifs accrete the gravity of déjà vu, we might realise we are elevated, by virtue of the literary medium, into a privileged vantage. Minor Detail seduces us into scouring each element for its hidden significance, as if it might verify what has been lost. Pulses of light, only temporarily invisible, capable of returning in their time.

Hiba Abu Nada, a Gazan poet killed in her home by an Israeli airstrike on October 20, 2023, wrote: “O little light in me, don’t die, / even if all the galaxies of the world / close in.”

*

Dog / الكلب

Of all the repetitions in Minor Detail, the most prominent might be the dog. In the first chapter, when the Israeli soldiers torture or rape the girl, the dog is always poised to augment her cries, an inarticulate witness to her trauma. The second half opens with a dog howling “incessantly”, keeping the Palestinian narrator from slumber. We are not told if it is the same dog, of course, but we believe it. Just when the woman toys with abandoning her project, thinking of the borders she must trespass, she is “racked by the dog’s howling”. Its opportune growls keep her from remaining numbed to Israeli settler-colonialism’s atrocities, however banalised.

Near the novel’s end, the narrator’s car is pursued by a dog that cannot stop barking. It eventually vanishes into clouds of dust and a mirage, seeming to suspend reality’s usual rules. It heralds the apparition of an old woman, and every indication points to her being a revenant spectre of the murdered Bedouin girl. She is around the girl’s age “if she hadn’t been killed”; she wears a black dress just as the girl “curled up inside her black clothes like a beetle”; her “blue veins” look like “lines on the maps”, an encoded tracery of memory. She might be, the narrator speculates, the source of the detail that would unlock the complete truth—the “incident as experienced by the girl”.

At this most crucial juncture, the narrator finds herself speechless. She mimics the girl’s silencing, as if inhabiting language through its loss. Samih al-Qasim, in Persona Non Grata, wrote, “There is no road but me (…) In my body is the next step.” But there is no step that the narrator, in her body, can take. The old woman vanishes into the hills, like a ghostly emanation of the landscape. The narrator’s layered failures culminate, finally, in her breaching a military zone and getting shot at.

Some reviewers and academics have written that the novel’s cheerless ending creates an inescapable cul-de-sac, mired in futility and despair. But such an interpretation conflates the narrator’s impotence with our own, and reimposes the violence of linearity on a novel whose heart thrums to the rhythm of the circular and the ghostly. Maybe the real question is: what imaginative apertures might Minor Detail crack open for us, if we remember that it is a fundamentally literary work, rather than a historical document or didactic treatise? If the novel teaches us to read it, as I believe it does, how can we think with the minor detail as a mode of being in, and relating to, a world of televised genocide?

*

Silence / الصمت

Adania Shibli, in an interview, spoke of tentatively finding her way to how “language reveals itself within the silence of writing”. In one essay, she quotes Mahmoud Darwish responding to an American journalist, “I am writing my silence.” Silence, she speculates, might emancipate language from its habitual distortions and abuses. For fascism, as for colonialism, the demonised other is the one “whose language is the first to be gouged”, as she wrote in an introduction to a dossier she edited.

More recently, after the shameful cancellation of her LiBeraturpreis award ceremony at the 2023 Frankfurt Book Fair, Shibli said, “Literature, for me, is the only place that accepts silence.”

Across her fiction, too, are scattered references to wordlessness: In her first novel Touch, silence signals the end of love, the greatness of God, the eternity of death; silence arrives, even, as an ear infection. Her sophomore effort, We Are All Equally Far From Love, mobilises silence to contour the alienation of missed connections and undelivered letters. In “Dust”, the narrator waits in line at an Israeli post office and takes “shelter inside her silence”, refusing to help the women in front of her despite her knowledge of Hebrew.

Watching Israel’s feeble, mendacious defence against South Africa’s genocide case at the International Court of Justice a few weeks ago, I wished silence would take over. The English lawyer Malcolm Shaw, in the midst of an awful plea, lost his page. He then released nervous laughter in spite of himself, as if he knew he were spouting nothing but lies. Soon after, his voice began to die on him; he cleared his throat multiple times, struggling to continue, and took a sip of water. I sent a wish to the heavens that every charlatan on that team would be contaminated by this miasma of coughing, stuttering, laughing, and losing their way.

Maybe the narrator of Minor Detail, struck dumb, momentarily enters into a kinship with these other avatars in Shibli’s oeuvre. With Shibli herself, we might understand her exemplary writerly signature—her clairvoyance of the minor—as allied with the muteness curled at the heart of literature. At the other end looms the loquacity, the alibis of international law, ceaselessly quibbling over the meaning of genocide as Palestinians in Gaza are being bombed, killed, buried under the rubble, attacked with white phosphorus, deprived of water and electricity every day.

*

Fiction / الخيال

The silence of pain, of faith, of the imagination, of al-ghayb. The silence of reading. What might be heard within it? In an extraordinary scene from Minor Detail I haven’t seen people talk about, the Palestinian narrator stays the night in Nirim, an Israeli kibbutz near the crime scene, against her better judgment. She chances upon a book of German expressionist art at the guesthouse, which contains excerpts of the artists’ letters to their spouses, dispatched from the battlefields of World War I. One missive, depicting the horror of inhabiting trenches alongside graves and corpses, notes: “It sounds like fiction (…) The existence of life here had already become a paradoxical joke.”

I noticed this vignette properly only on my fourth complete rereading. The word “fiction” caught my attention; I turned to the Arabic, and found that Shibli used khayal. Loosely, khayal refers to immaterial forms or images, fanciful dream-visions and shadowy supernatural apparitions. From its initial reference to the spectral beloved in pre-Islamic poetry—itself replete with ruins and sorrow—khayal evolved to acquire the meaning of ‘to invent’, ‘to imagine’. A more straightforward translation in Minor Detail’s context might have been ‘fantasy’.

But Jaquette chose ‘fiction’; I couldn’t help but think of the genre in which the text is implicated, the way it is marketed as fiction on its back cover. In Arabic, the standard word for novel, assimilated into the dominant currents of the world literary system, is riwaya. We don’t often think of its older meanings. As Abdelfattah Kilito scrupulously reminds us, riwaya used to refer to the act of oral transmission, whether of poetry, narratives, or Prophetic hadith. In Minor Detail, the narrator declares her impulse to retell the girl’s story; the word “story” is from riwaya.

Riwaya, then, not as fabrication, but as the imperative to witness without abstraction. As the necessity to retell, to reread, to retread, to translate—from German to Arabic to English, between the Holocaust and the Nakba of 1948 and today’s ongoing genocide in Gaza. As the unceasing call of the dog, the urgencies of history in its demand to be resurrected and relayed. As the interplay of truth and fiction, the fragilities of memory and language, the making real of khayal in all its silence. Remember Refaat Alareer, killed by an Israeli airstrike in Gaza on December 6, 2023, who wrote: “If I must die/ let it bring hope / let it be a tale.”

Shortly after closing the book of letters, Shibli’s narrator is awoken by distant shelling. It might be Gaza, or Rafah. Insulated as she is in an Israeli kibbutz, the shelling comes to her as rumbling, like a rhythmic drumbeat, abstracted from all the destruction and dust to which she has been inured. Sounds just like fiction. But then she thinks, “I feel a strange closeness with Gaza.”

*

Grass / الأعشاب

Minor Detail’s risky novelistic gambit might be that there are no guarantees it will find its addressee; it might not wash up on the right shore. Where the Palestinian narrator cannot transcend the bounds of her era, we are left to take on the task of imaginative connection. See how we are positioned to intimate the traces of what remains:

[…] one cannot rule out the possibility of a connection between the two events, or the existence of a hidden link, as one sometimes finds with plants, for instance, like when a clutch of grass is pulled out by the roots, and you think you’ve got rid of it entirely, only for grass of the exact same species to grow back in the same spot a quarter of a century later.

She is, of course, talking about the uncanny coincidence that started it all, the convergence of her birthday and the Bedouin girl’s murder on the same date, the latter occurring a quarter-century earlier. In this passage, the clutch of grass serves as analogy for the “hidden link”, but the words also constitute a near-verbatim reproduction of the literal “clutch of dry grass”, “ripped up by the roots” in the first chapter, idly sighted by the Israeli commander after the platoon massacres a group of Arabs.

While the literal has been transmuted into the metaphorical, we are nonetheless enjoined to discern the “hidden link”, to believe that the grass stands in for nothing but itself. Maybe language itself enacts this nagging persistence, through its almost word-for-word replication. Language, textured by rhythm and repetition, organised within the literary, can now “grow back in the same spot”, in the desert of our minds. Language articulates the encrypted secret of vanished lives to be listened to, in their refusal to be extinguished, carrying it to us across time.

Shibli anticipates a reader to come, one who might not yet be here. Sarah Aziza tells us that real witness must begin in mystery, in the singularity of each lost life, which we can never know: “Perhaps the fundamental work of witness is the act of faith—an ethical and imaginative leap beyond what we can see.” What Minor Detail transacts, and asks of us, is a leap of faith.

*

Gaza / غزّة

In a brief meditation of Shibli’s, entitled “A Lesson in the Nature of Revolution”, she sketches a picture of the garden around her parents’ house, and attends specially to the caper bush, its white flowers blossoming through the year, its round leaves “equally unruffled”, staying light green regardless of whether it is “autumn or spring—even an Arab spring”.

Without the essay’s title and this one surreptitious reference, the entire piece would be an innocuous horticultural memoir. I have long associated Shibli with such oblique smugglings; it is, to me, one of the sources of her oeuvre’s enduring potency. If there is anguish, it gleams only at an angle, under the light.

The caper bush resists uprooting. It keeps growing back, “a reminder of the truth of that piece of land”. I am reminded as much of the prickly pear cactus, or sabr, evoked with such longing in Saree Makdisi’s Tolerance is a Wasteland, even as he recounts the thick forests planted by the Israeli regime over the ruins of Palestinian villages brutally evacuated in 1948:

It’s a curious feature of the prickly pear, however, that it is almost impossible to completely eradicate; as long as even a tiny rhizome remains in the soil, the plant will come back. And so, wherever one goes in Israel’s artificial forests, or wherever one wanders outside the forests, one consistently comes across prickly pear bushes erupting from the earth or bursting out from between the pine or eucalyptus trees planted over them. And, inevitably, close by, one encounters the ruins of Palestinian homes.

Amidst the ruins, I want to read Shibli’s writing in Minor Detail and elsewhere, especially in its most apparently inert and disconsolate moments, as a pedagogy of hope, of waiting, and of revolutionary becoming.

Maybe, the black dot I wiped off that day can appear on another book, another map of the present. Or a subjunctive map—one remaining to be plotted, traversed, lived, whose name is as untranslatable as Gaza, whose ineradicable lines limn a cartography of the damaged world.

Alex Tan is Assistant Managing Editor at Asymptote and, following Rasha Abdulhadi and Fargo Nissim Tbakhi’s call to hijack the space of the bio, would like to express unconditional support for Palestinian liberation and call on you to “get in the way of the death machine”, wherever and whoever you are. For starters, consider donating an e-sim, fasting for Gaza, and sharing the words of Gazan writers.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog:

- Call for Submissions: On Palestine

- From Palestine to Greece: A Translated Struggle

- Reading Palestine in French: In Conversation with Kareem James Abu-Zeid