With inimitable lyricism and an impeccable sense of balance, Balsam Karam’s The Singularity addresses some of the most complex elements of contemporary social reality. Yet, even as the thrilling narrative is intricately braided with the brutal realities of loss, displacement, motherhood, and migration, the novel’s innovative structure and bold, surprising style elevates it beyond story, revealing an author who is as precise with language as she is with illustrating our mental and physical landscapes. In starting off a new year of Asymptote Book Club, we are proud to announce this work of art as our first selection of 2024.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

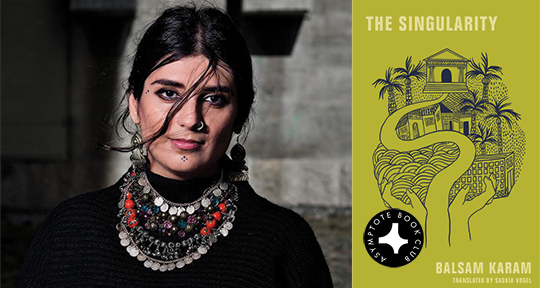

The Singularity by Balsam Karam, translated from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel, Feminist Press/Fitzcarraldo, 2024

Meanwhile elsewhere—two women perched on the precipice in a tangential encounter, spun together by forces outside their control, as if in the singularity of a black hole. One woman is about to jump off the edge, bereft after the loss of her teenage daughter; the other will frame this moment as the beginning of the end for the child in her womb. No need for spoiler alerts here: what might feature as the climax in a more conventional narrative is laid bare in The Singularity’s prologue. That it nevertheless remains absorbing to its very end is a testament to the depth of feeling and dexterity with which the Swedish-Kurdish novelist Balsam Karam orchestrates the rest of this novel about grief, loss, migration, and motherhood.

Given this jarring beginning and its atypical (or absent) narrative arc, it is perhaps no wonder that as the rest of this novel unwinds, we are met with multiple displacements in time and perspective, echoing the geographical dislocation of the two central figures—both of whom are refugees—and the all-encompassing, omnipresent nature of the trauma they experience.

Before throwing herself off a tourist-thronged cliff in a bullet-ridden city, the first woman has been searching for The Missing One: her seventeen-year-old daughter, who never came home from her cleaning job on the corniche a few months earlier. After fleeing from their home, receiving scant help from the relief organization that occasionally visits with a “hello and how are you all then here you go and we’ll be back soon, even if it’s not true,” and finding little sanctuary living in a tumble-down alleyway at the fringes of this unnamed city, the mother seems to experience the disappearance of her daughter as the final loss that makes her lose herself. “What mother doesn’t take her own life after a child disappears?” the first woman asks the universe, or “when a child dies?” the second woman asks her doctor.

Disconcertingly, this second woman is “you”. The reader is thus thrust uncomfortably into identification with someone whose experiences (as we are reminded later in the novel) are not only outside those of a Swedish or English-speaking Western reader, but also—despite the universalising nature of the novel’s abstraction from clear geographical, cultural and temporal markers—very much singular. This “you” comes to the forefront in the second and third parts of the novel, which trace her experience in hospital, as well as her conversations with doctors and counsellors while she refuses to birth her dead child (exerting, perhaps, what little control she feels she has left); it then jumps back in time to end with short, sharp vignettes—dotted with the tenderness of familial love but also teeming with the indifference, tone-deafness, and outright racism of her host country—that chart her path from the loss of home and murder of her best friend to the loss of her first child. “Can traumas be ranked?” both women ask.

These unsettling questions are not given a clear answer; or perhaps, the novel rather allows for each character to answer it in a different way. So often in storytelling, we follow a small number of central characters down a linear path that, through the imposition of this order and focus, implies clear beginnings and ends, and creates a hierarchy of emotional and social importance. But what, this novel seems to suggest, if this is not how the experience and legacy of (forced) migration and grief play out? What if every new experience is saturated with what has come before? How does writing, linear in its essence, capture the simultaneity of multiple bodies in space or the tumble of coexisting thoughts and feelings in a single mind, where “the force of gravity is so strong it can’t be calculated”; how can it “show how no space remains between bodies in the singularity“?

In trying to do just this, Karam stretches the limits of conventional narrative writing, deftly infusing the novel with techniques borrowed from musical composition, lyric, and theatre; the result is a work of true formal experimentation without self-consciousness or artifice. The medium is the message.

The futile searching and monotonous subsistence of the characters in the first section, “The Missing One”, is shown to us in a repetitive, almost hypnotic prose that sits somewhere between a funeral dirge and a fugue, and suspends the action in a single, seemingly never-ending day. Each of its brief sections begins with a variation on the same scene setting—a Friday in late summer in a seaside town—and each time, the words are slightly rearranged and supplemented with new details or perspectives, usually of those at the margins of society. This syntactic flexibility is masterfully handled by translator Saskia Vogel, who manages to make the prose feel somewhere un-English: unfamiliar but not awkward, and never like translatorese. Vogel and Karam’s stylistic adroitness is highlighted in the comparatively straightforward, conventional sentence structure of the novel’s third act.

As well as reinforcing the repetitive nature of the search, the variations in the first section enable multiple perspectives to be overlayed, mimicking their concurrence; by circling back over and over again—first to the mother, then her three surviving younger children, then their grandmother—it becomes easier for the reader to hold their simultaneous action in the mind’s eye, like a verbal kineograph. After nearly a hundred pages of these variations, however, the pressure of the mother’s devastating single-mindedness, the retreat of the grandmother, and the abandonment of the younger children becomes almost overbearing, thus also mimicking the oppressive nature of the characters’ own trauma and grief. When Saturday finally arrives, it feels abrupt and shocking. The search for The Missing One is over. The mother is dead. The children are alone.

This highlights just some of the many linguistic and narrative techniques employed by Balsam and Vogel to fuse the novel’s form with its content. The omniscient narrator collides the past and present with the future through shifting, unstable tenses, revealing the pervasiveness of (especially traumatic) memory and questioning the genesis of (especially intergenerational) trauma and loss. In the second section, snippets of conversations that “you” has with her doctors are alternated with memories and the conversations she has with her mother. This counterpoint shows how we can relive one experience while engaging in a completely different external reality; and how deeply traumas can be intertwined. If they cannot be ranked, perhaps it is because one trauma is never entirely independent of the those that have come before.

All this feels rather pessimistic, but The Singularities does not wallow in despair. With the children who are left behind, there is a glimmer of a potential better future. They are the only central characters whose names we learn, and though they live in squalor and on bad days fill their mouths with sharp stones, Karam also allows them to experience beauty, pleasure, and hope. Despite abandoning them, the mother leaves a parting gift by sending other children to the alley with whom they might build a future away from the corniche. The novel seems to suggest that these children may find a path beyond waiting, and work through their rehearsal of fading memories toward a more settled life.

The third and final section of the novel—the epode, if you will—offers another way forward, despite being called “The Losses”. Although it traces a succession of challenging episodes in the second woman’s experience of migration and integration, it does so with a sharpness and clarity that can be read as the “you” having emerged from the deepest morass of her miscarriage, where if “someone asks you to tell them what it was like, you tell them you remember, but each time using new words and in a different order”. Here, events can, to a greater extent, be unstuck from one another. In this mode, the novel pinpoints the countless micro and macro losses that accompany migration, and comments most starkly on the failures of the Western world to accept or understand the Other. At the same time, it also shows most clearly the resilience and insight of this refugee family. Describing the rudeness and imposition of a White passer-by, “your” mother comments, “You have to understand that people like her are to be pitied. . . their ignorance, how little they’ve experienced in life.”

Through the looping nature of its narrative and the overwhelming distress of its two main characters, The Singularitty shows that certain traumas cannot be erased. They form an enduring part of the subject who experiences them, but they do not necessarily have to be worn like shackles, nor must one sink under their weight. “I come from a tradition of loss,” the second woman tells her counsellor, “and I don’t intend to continue in that tradition”. At the same time, however, the world’s violence and grief cannot simply be whitewashed over to make pretty seaside towns, from which tourists return home with the souvenir of false insight. Instead, perhaps, we might continue to read novels such as this, which take the limits of our language and our blinkered versions of reality to task, and which encourage us to listen to others instead of marginalising and erasing their experiences.

Rachel Stanyon is a translator from German into English and a senior copyeditor with Asymptote. She holds a master’s in translation and in 2016 won a place in the New Books in German Emerging Translators Programme. Her first full-length non-fiction translation has recently been published with Scribe.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog:

- Announcing our December Book Club Selection: On the Isle of Antioch by Amin Maalouf

- Announcing Our November Book Club Selection: Kinderland by Liliana Corobca

- Announcing Our October Book Club Selection: A Shining by Jon Fosse