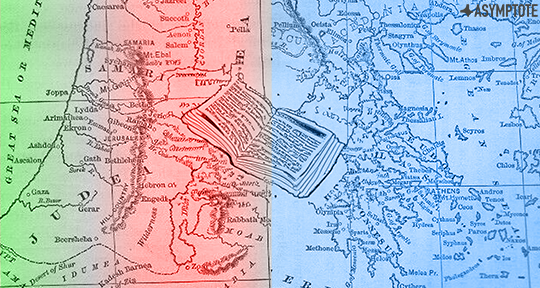

Palestine and Greece have long enjoyed a strong relationship of solidarity and friendship, fortified by mutual assistance during political tumults, expressions of recognition, and profound demonstrations towards peace and independence. In this essay, Christina Chatzitheodorou takes us through the literature that has continually followed along the history of this connection, and how translations from Arabic to Greek has advocated and enlivened the Palestinian cause in the Hellenic Republic.

Following the Israeli invasion of Lebanon and the siege of Beirut in 1982, the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) was forced to leave the city. Its leader, Yasser Arafat, then fled Beirut for Tunisia, and, in fear of being captured or assassinated by Israel, he asked his Greek friend Andreas Papandreou for cover. The two had previously joined forces during the dictatorial regime in Greece known as Junta or the Regime of the Colonels, in which Arafat supported the Panhellenic Liberation Movement (Panellinio Apeleutherotiko Kinima/PAK) founded by Papandreou, and had also offered training in Middle Eastern camps to the movement’s young resistance fighters.

Arafat arrived then from war-torn Beirut to Faliron, in the south of Athens. He received a warm dockside reception by the then-Prime Minister Papandreou and other top government officials, as well as a small crowd consisting mostly of Greek Socialist Party (PASOK) members and Greece-based Palestinians, who stood by chanting slogans in support of the Palestinian cause. Papandreou called Arafat’s arrival in Athens a “historic moment” and assured him of Greece’s full support in the Palestinians’ struggle; after all, while Arafat was coming to Athens, accompanied by Greek ships, pro-Palestinian protests were taking place around the country almost every other day.

Although our support and solidarity with the Palestinian cause neither began nor stopped there, that day remains a powerful reminder of the traditional ties and friendship between Greek and Palestinian people. But more importantly, it comes in total contrast with the position of the current Greek government. Now, despite the short memories of politicians, it is the literature and translations of Palestinian works which continue to remind us of Greece’s historical solidarity to Palestine, particularly from left-wing and libertarian circles.

Throughout the 1970s and 80s, a pro-Palestinian sentiment was reflected in various translations of Arab and Palestinian literature, including many works by the PLO. Amidst the contributors to this archive were the General Association of Palestinian Students (particularly active in Greece during the 1970s and 1980s), which translated and published two anthologies of Palestinian poetry. The first, Poihmata tis Palaistiniakis Epanastasis (Poems of the Palestinian Revolution) was published in 1977, and included Mahmoud Darwish’s poem “تَحَدٍّ”—known in English as “Defiance” and in Greek as “proklisi” (challenge). The second collection, entitled Palaistiniaki Poihsi (Palestinian Poetry), included selected works of Tawfiq Ziad, known for his “poetry as protest”, and Samih al-Qasim, whose poems were influenced by the Panarab ideology of Nasserism during the post-1948 nationalist era. Here, Darwish also appeared through his well-known poem “Identity Card”, translated as “tautotita” in Greek:

Write down!

I am an Arab

You have stolen the orchards of my ancestors

And the land which I cultivated

Along with my children

And you left nothing for us

Except for these rocks . . .

Another pivotal writer that underscored these times was Sahar Khalifa. In December 1982, three months after the Sabra and Shatila massacre, Kastaniotis Editions first published Khalifa’s book Al-Subar (Wild Thorns) as To Chroniko tis Frankosykias, in a translation by Isabella Bertrand. The book tells the story of a young Palestinian, Ushama, who returns to his hometown of Nablus with a mission: to blow up the daily buses going to Tel Aviv. However, this plan is complicated by the fact that Palestinian workers also head to the city on these buses, and among them are his friends and family members. In this complex narrative, Khalifa illustrates the realities of colonised people and the resulting psychological impact, from everyday concerns of providing for their families to calls for resistance and dissent against the occupation.

In 1983, well-known writers were introduced to Greek readers by way of an anthology, Synchronoi Palaistinoioi Pezografoi (Modern Palestinian Prose Writers); among others, the compilation included works by the Palestinian revolutionary Ghassan Kanafani; the long-term spokesman of PLO, Mahmoud Labadi; and the Palestinian poet Taha Muhammad Ali.

Following the warm relations between Greece and Palestine in the 1980s—with Papandreou inviting Arafat in 1981 to visit Athens with head of state honours (effectively recognising his organisation)—many works were also translated during and after the First and Second Intifada. In various titles and left-wing or libertarian publications, Greek translators wrote the Arabic word “intifada” in Greek as “eksegersi”: uprising. However, certain texts simply transliterated the word. In many progressive publications following the First and Second Intifadas, “intifada” remained intact as ιντιφάντα, demonstrating the importance of the Palestinian cause as a liberatory struggle for all oppressed people of the world, and paying homage to the Palestinian people. Thus, the word became a part of the Greek language and vocabulary—an Arabic word that emblematised the Palestinian people’s struggle for land, dignity, and freedom, confirming in essence Kanafani’s words that “the Palestinian cause is not a cause for Palestinians only, but a cause for every revolutionary”.

In the wake of the First Intifada, the 90s in Greece also saw works such as Evangelos Parameritis’ Odi tin Palestini (Ode to Palestine), dedicated to the “Palestinian fighters who are heroically fighting for the right to live freely”; and Kanafani’s 1999 novel Men in the Sun, published by Kastaniotis Editions in Alatras Nasim’s translation—who was himself a member of the General Association of Palestinians Students in Greece during the 1980s, as well as a co-founder of the first Greek-Palestinian Support Committee of the First Intifada.

Works surrounding Palestine continued to appear on the Greek literary scene in the new millennium, from both local writers and though translations. In 2002, the communist and antistasiakos (resister) Nikos Kepesis paid homage to the Second Intifada with his book Palaistini! Deuteri Patrida mou esi Glikia Mou! (Palestine! My Second Homeland, My Sweet You!). In his words: “The collection is an expression of my warmest support for the Palestinian people and their revolt against Israel. Each of my poems came spontaneously out of my heart and mind.” In 2007, Khalifeh’s Wild Thorns was re-published, this time by Kedros Editions. One year later, Greek readers were introduced to the powerful voice of Karmi Ghada through her memoir, translated into Greek as Fatima – Anazitontas mia Nea Patrida in 2008; known in English as In Search of Fatima: A Palestinian Story, the work reflects on Ghada’s memories of exile, refuge, and nostalgia for the lost homeland. Despite being a distinctly personal narrative, it speaks on the experiences of the million Palestinians who have been forcibly displaced, and of memories as the only salvageable remnants from a lost world.

Towards the end of the decade, Khalifeh’s Pyrini Anoixi (The End of Spring), set during the second Intifada, appeared. Revolving around the bookseller Fadel Al-Qassam and his two sons, all living within the context of occupation and apartheid, the novel captures the heroism, sacrifice, militancy, political betrayals, and contradictions that Palestinians have to endure. A powerful statement as to life under occupation, it would be followed one year later by another moving portrait: Mahmoud Darwish’s poem “Katastasi Poliorkias” (“A State of Siege”). The poem, consisting of short lines surrounding the absurd situation prevailing in Ramallah during 2002, appeared in a beautiful translation by Giorgos Blanas, but the preface is what stands out. In it, Blanas compares the poem to “Eleutheroi Poliorkimenoi” (“The Free Besieged”), a poem by Dionisios Solomos—Greece’s national poet. Darwish and Solomos, despite living in different eras and political contexts, are found in a dialectic relationship through their work. As Blanas writes, the poem transmits

the same fundamental feeling from which Solomos’ poem “Free Besieged” is derived: the contrast between the beauty of life and the hideousness of impending death. . . The surrounding nature—in Solomos’ [poem]—and furthermore the surrounding people (neighbours, friends, relatives)—in Darwish’s [poem]—enchant the besieged, who forgets, just for a moment, that his life is not at all what he had temporarily aspired to, but an absence made from the enemy and myriad absences of all the voluptuous aspirations, of so many familiar dead people.

Following yet another attack on Gaza in September 2021, Shubair Sana’s Stin Gaza Tolmo na Oneireuomai (In Gaza I Dare to Dream) was translated by the Antifa Sisterhood, an autonomous women’s group dealing with gender issues and everyday sexism. In this autofiction, Shubair documents the daily life of a Palestinian woman, mother, teacher, and Gaza resident without descriptive embellishments—her pen moves fast because the clock is clicking, and the time shows seventy-five years and ninety days. Her sole concern is to describe the reality of a protracted war: a war that became visible to many only on October 7, but which, for the Palestinians, has been ongoing since 1948.

The Hamas operation on October 7 and the ongoing genocide in Gaza has again initiated a surge in both literary and non-literary publications on and for Palestine; the war has become a moral litmus test, and this is, in turn, reflected in art, poetry, and songs. In Greece, a compilation has recently been published as an homage to Gaza in resistance: the collection, Na Akoustei Mexri tin Gaza: Leuteria stin Palaistini (Let It Be Heard All the Way to Gaza: Freedom to Palestine), includes fourteen poems by ten poets, and demonstrates the rage for the Israeli crimes committed in the region. Literature always exists in a dialectic relationship with the past and present, moving beyond humanly imposed borders; just like how Solomos’ and Darwish’s poetry can speak to each other through their besieged status, the ten authors wish to speak to the besieged Palestinians in Gaza. Now, as before, Greek poets are drawing from the heroic struggle of the Palestinian people; with just a pen in the hand, they are sending a message of solidarity in verse.

In December 2023, the 1980 collection Palaistiniaki Poihsh (Palestinian Poetry) was republished, this time with an added introduction from the historian Giorgos Margaritis, who gives an overview of the Palestinian cause, as well as the nation’s literary history. This archive was then further enriched by another anthology of Palestinian poetry translated by Persa Koumoutsi—one of the most-well known Arabic translators in Greece; the collection, Gia Mia Eleutheri Palestini (For a Free Palestine) by Entypois Editions, includes poets who had already been introduced to the Greek-speaking audience, such as Zakaria Mohammed and Darwish, but more importantly, it also contains poets who are appearing for the first time in Greek: Najwan Darwish, Mosab Abu Toha, Maya Al-Hayat, and the Palestinian-Egyptian poet Tamim al-Barghouti.

Lastly, in the third issue of the literary magazine Vlavi (which means damage or malfunction), the readers are introduced to a segment of Adania Shibli’s book Minor Detail; the editors of the magazine had decided to use the “most precious and personal printing space of our magazine as a minimal tribute to the one who was deprived of it”, in reference to the Frankfurt Book Fair’s decision to call off the author’s award ceremony and public discussion of her book.

Yet, despite all of these aforementioned works—many of which have been translated by politically engaged translators—there are many Palestinian authors whose voices are still non-existent or barely present in Greek. Though readers have access to some of Kanafani’s work, his novella, Umm Saad, is a title that comes to mind when one considers such absences. The novella tells the story of a Palestinian woman with the same name, narrating her struggle in first person. Yet, her story does not solely represent herself, but myriads of Palestinian women who have become symbols of resistance and revolt. The book demonstrates that the war is not only the “business” of men; Palestinian women have always being on the forefront, as mothers, fighters, writers—acting in roles beyond Western essentialised ideas that deny them their autonomy. Another writer is Fadwa Tuqan; though some of her poems have recently been translated, readers of Greek would greatly benefit from a broader access to her work—including the beautiful piece, “The Deluge and the Tree”.

Arabic poetry appears regularly in Greek (many by way of the prominent translator Persa Koumoutsi), yet translations of Palestinian works are somewhat set apart from this group. Palestinian writing has never existed solely as literary works. Rather, they have always served another important purpose: acting as a ‘translation protest’ (both as an extension and a part of a dialectical relationship with resistance literature), of which the aim is to amplify the voices of Palestinians and, by doing so, help readers learn about their struggle. In this, the Palestinian people have long inspired artists, writers, and revolutionaries from around the world, including those of Greece. They have and are continuing to teach us that utopias are not solely objects of fantasy but are objectives to be built and lived—and it is at the intersection of art and revolution that we can create them. When it comes to translations from Arabic to Greek, such writings embody this intersection, and remain one of the most vital and necessary ways to amplify Palestinian voices and build solidarity with the oppressed, and not for the sake of the oppressed. This literary exchange has always been an important factor in moving beyond essentialised ideas of what resistance should look like, and as we continue to face a world in which resistance is necessary in the face of impossible violences, it is now more crucial than ever—in Greece, in the world—to listen directly to the Palestinians, their experiences, and their desires for freedom.

Christina Chatzitheodorou is a PhD candidate at the University of Glasgow, focusing on women’s participation in left-wing resistance movements during the Second World War. Originally from Greece, she speaks Greek, English, French, Italian, Spanish, a bit of Portuguese, and Turkish—and learning Arabic. Along with her PhD, she is currently working on a visual archive focusing on Greek solidarity to Palestine.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: