This week, our editors around the world bring news as to how different literary initiatives and publications are help shaping the present. From writers who embody multiculturalism and unity, to works of solidarity and hope, read on to see how writers, readers, and artists are working to shed light on what matters.

Sofija Popovska, Editor-at-Large, reporting from North Macedonia

“Rarely has any Macedonian poet attracted as much attention among theorists, literary historians, and philologists as [Kočo] Racin. Racin was . . . a pioneer in the artistic expression of the mother tongue, . . . an example of an ideal revolutionary and, in the end, a victim. He was the most honorable and most honored thing that the Macedonians had in the period between the two wars,” writes Goran Kalogjera, a prominent Croatian comparatist and scholar of Macedonian studies in his book, Pogled otstrana. Racin (1908 – 1943) (Side view. Racin (1908 – 1943)). Recently, this important biography was translated into Macedonian by Slavčo Koviloski, and published by Makedonika Litera Press.

Kosta Apostolov Solev is a canonical figure in Macedonian literature, hailed by some as the founder of modern Macedonian poetry. He is best known under his penname, Kočo Racin, which was derived from the name of his lover, Rahilka Firfova-Raca—a gesture indicative of his support for the socialist women’s movement. He himself was a political activist, participating in the translation of the Communist Manifesto into Macedonian, and acting as editor for several communist magazines. His political leanings had contributed to his mysterious and untimely death; mortally shot by a printing-house entrance guard in June 1943, some speculate that Racin had been purposefully targeted by the communist party, having fallen out of favor with them around 1940. However, his activism effectuated his ties to other cultures, enriching his literary oeuvre. Aside from his mother tongue, he wrote texts in Bulgarian and Serbian, and was published all over the Balkans. Kalogjera stresses this multilingual, multicultural aspect of Racin’s output in Pogled otstrana, noting his importance to Croatian culture.

In a time when “balkanisation” is used to denote discord and fragmentation, authors like Racin and Kalogjera serve to rekindle a much-needed sense of fraternity between Balkan cultures. Koviloski embraces a comradely cadence in his foreword to Side View, writing: “Kalogjera concludes [that Racin] remains the most famous Macedonian writer in Croatia. Thus it is fitting that we should conclude by saying that Kalogjera is one of the most famous scholars of Macedonian studies, not only in Croatia, but also in Europe.”

Rene Esau Sanchez, Editor-at-Large, reporting from México

The beginning of the new year marks the end of the “Guadalupe Reinas” Marathon, an online reading challenge that first started as a small book club, and has since become a literary phenomenon. The Marathon was created in 2017 by the association LibrosB4Tipos, with the intention of encouraging the public to read more books written by women; in fact, the name “Guadalupe Reinas” is a wordplay on “Guadalupe Reyes,” an expression often used in Mexico to indciate the holidays that start on December 12 (Día de la Virgen de Guadalupe) and end on January 6 (Día de Reyes).

The Marathon consists of reading up to ten books written by women between those dates, and has established itself as a way to celebrate women in literature and socially engage in their cultural representation. This year, participants included authors like Brenda Navarro (Mexico-Spain) and Andrea Chapela (Mexico), editors, journalists, magazines, bookshops, and independent publishing companies like Almadía or Sexto Piso, all completing the challenge or suggesting books from their own catalogs.

Rules change every year, and in this edition, the reader was meant to read: a book from a winner of the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Literary Award; a book on nature; an anthology written and edited by women; an author that has inspired you to create; a book from an author mentioned in a movie, TV show, or song; a book from an author you consider essential; the seventh book or publication from an author; a book on political and economical alternatives; a book you could not read in another Marathon; and a book from LibrosB4Tipos book club selection.

Some of the authors read during the Marathon include Maria Ospina Pizano (Colombia), who last November won the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Award; Cristina Rivera Garza (Mexico), who became in 2023 the first woman to enter Mexico’s National College as a writer; Sylvia Plath (United States); Miriam Toews (Canada); Doris Lessing (United Kingdom); and Gioconda Belli (Nicaragua).

Carol Khoury, Editor-at-Large, reporting from Palestine

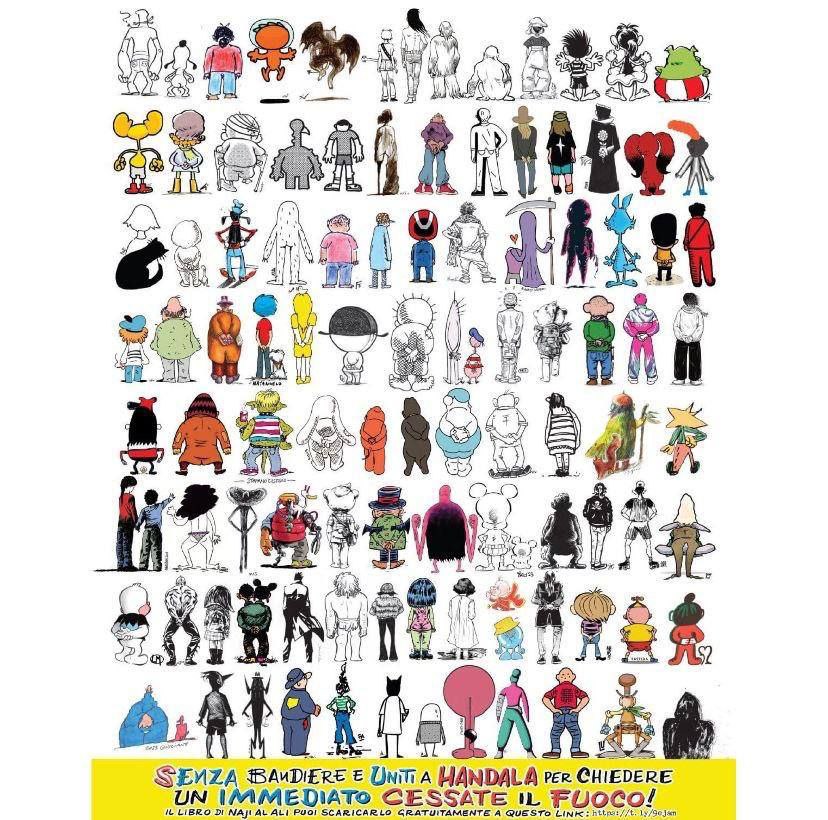

In a historic anti-war initiative, Italian comic strip artist Francesca Ghermandi, with her peers, have launched a movement that has now garnered support from over eighty Italian comic artists. Paying homage to Naji al-Ali’s iconic character, Handala, the artists portrayed hundred and four famous comic characters with their backs turned, encircling Handala. This profound act of solidarity conveys a potent message for an immediate #CeaseFireNow, drawing inspiration from Handala’s spirit of resilience and defiance.

Handala, a ten-year-old refugee armed with hair like a hedgehog, symbolically rejects injustice. With hands clasped behind his back, he dismisses imposed solutions, challenging what Al-Ali criticized as “the American way.” Handala’s perpetual youth is intricately tied to the homeland’s return, defying conventional laws of nature, and his evolution into a global symbol with a human perspective continues to resonates deeply with those who see him as a representation of collective consciousness.

For those seeking more information, the initiative provides downloadable files for spreading the message freely. Additionally, a book dedicated to Handala’s history and Naji al-Ali’s work, titled “Filastin,” can be downloaded for free.

Over the years, Handala has become a symbol of the Palestinian struggle for freedom and justice. Naji al-Ali, the Palestinian cartoonist who created Handala, tragically lost his life in 1987 after being shot in the neck outside the London offices of Al-Qabas, a Kuwaiti newspaper for which he created political caricatures.

As the Italian comic artists collectively turn their characters backs to face us, they amplify the urgent call for a ceasefire. This tribute resonates with Handala’s timeless message, providing a visual testament to the plea for peace during tumultuous times.