In our final round-up of the year, we’re presenting a selection of titles that capture the human condition with various, masterful depictions and incisive intelligence. From Italy, the first volume of artist and writer Guido Buzzelli’s collected works present scrupulous and unwavering critiques of society; from Hungary, the master poet Szilárd Borbély writes the life of Kafka in relation to his father’s; from Cuba, a stunning bilingual collection from Oneyda González explores the surreal nature of the mirror.

Buzzelli Collected Works Vol.1: The Labyrinth by Guido Buzzelli, translated from the Italian by Jamie Richards, Floating World Comics, 2023

Review by Catherine Xin Xin Yu, Assistant Director of Outreach

What happens if, at the end of a normal workday, a sudden blast razes the world to the ground and you become one of the few survivors? Or if, waking up on an ordinary morning, you find your head and limbs dissociating from your torso and taking off on their own? Setting the scene with these Kafkaesque premises, Italian comic master Guido Buzzelli explores the monstrosity and power of dystopian societies in his graphic novellas, The Labyrinth and Zil Zelub, with a compelling visual language that is dense yet dynamic.

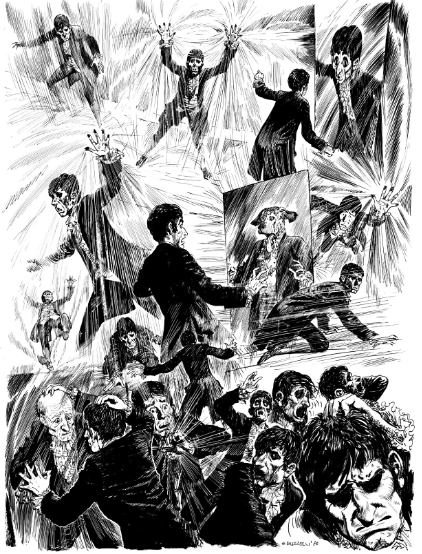

Buzzelli stands apart from his peers in every way—style, form, and theme. Born into a family of artists and trained in figure drawing, he is lauded as both “the Michelangelo of monsters” for his naturalism, and “the Goya of comics” for his chimeric blend of the real and the fantastical (as pictured below). He was also one of the first Italian comic artists to tackle complex literary subjects in uncommissioned, standalone works, counter-current to the Italian comics industry of the 1960–70s that pumped out commercial series with fixed characters and simplistic plots. As a self-proclaimed “man in doubt,” Buzzelli also rebelled against the progressivism of 1960s Italy, satirising the hypocrisy of political discourse and the violence of utopian mirages while alluding to the political upheaval at the time, from terrorist bombings to murky electoral campaigns.

In The Labyrinth, after the apocalyptic explosion, the protagonist Marcello Sforvo is forcefully taken into an underground society where humans are made to have animal parts grafted onto them. When he finally escapes, he ventures into an ethereal Sphere inhabited by chosen individuals who have perfect bodies—assembled with parts taken from people outside their elite community—and act with an impeccable rationalism that negates every trace of human emotion. These societies are two sides of the same coin when it comes to the inherent violence of power, here enacted by institutions hijacking, mutilating, re-forming, and distorting bodies into monstrosities, all in the name of progress, but Sfovo’s inability to find his place in either society is not due to these brutal circumstances, but also his inherent flaws. Eager to join the Sphere, he is subjected to multiple character tests but fails them all. Particularly telling is the final test, in which he has to find the only accurate mirror in a labyrinth of distorted reflections, and it is his resulting lack of self-knowledge that ultimately leads to his expulsion from this “ideal” society.

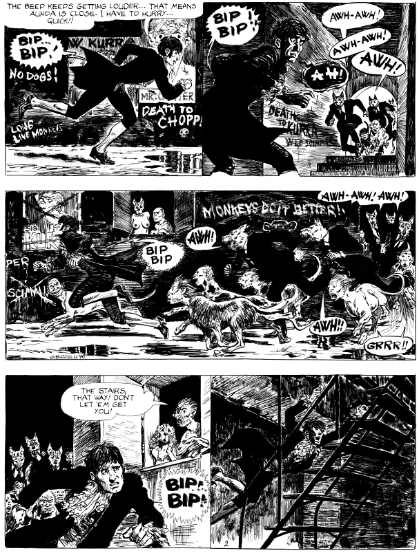

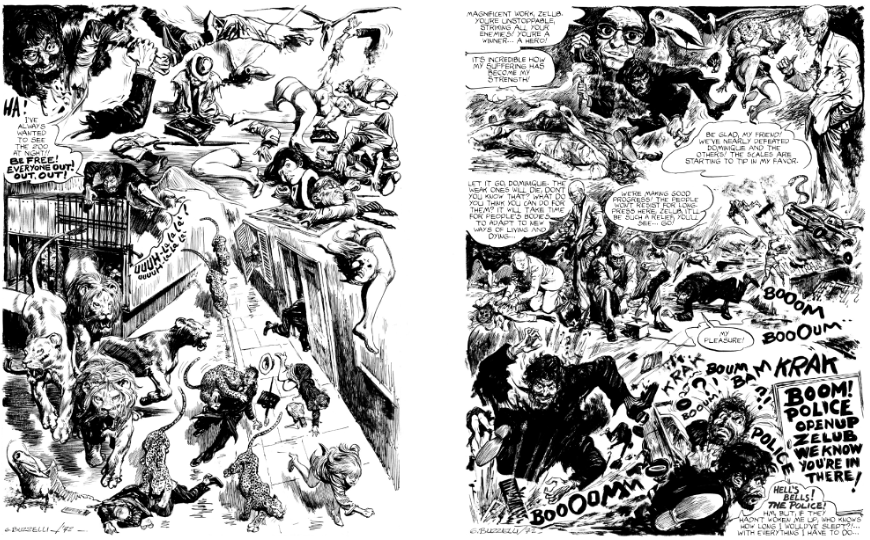

Similarly dark and introspective, Zil Zelub (an anagram of Buzzelli) traces the physical and psychological dissociation of its homonymous protagonist in a plutocracy where even political opponents share imbricated economic interests. Power and profit reinforce one another, and both are here controlled by the tycoon-politician Choky, the biggest shareholder of a deadly chemical factory, Plastik. The internal struggle of Zil Zaleb, a self-righteous musician with little talent and discipline, is externalised in the form of his dissociating limbs, each with its own vice, be it lust, greed, violence, or cruelty. His yearning to assert himself as a “hero” ends up being manipulated by Choky and his men, who encourage Zil to give in to the diabolical urges of his rogue limbs and wreak havoc in the city.

Throughout, Buzzelli moves fluidly between his visual and verbal language. In The Labyrinth, the depiction of human-monsters is simultaneously supple and grotesque, beautiful in their horror. The hellish landscape of the underground world is echoed by the dark tone of the drawings, while the omnipresent restrictions of the celestial Sphere is depicted with dense curtains of fine lines. At the same time, the dialogues mock empty political discourse, peppered with unsubstantiated buzzwords like “common good,” “egalitarianism,” and “humanitarian purpose,” and the horror is heightened by dehumanising language that reduces the human body to “stuff,” “specimen,” and “anatomical spares.” Of course, the irony is not lost on the reader when Buzzelli/Richards calls a body forcefully subjected to medical experiments a “subject,” sharply in contrast to the individual’s total lack of agency and autonomy.

In Zil Zelub, the force of chaos is often embodied by animals, be they the infectious plastic birds born of pollution, or beasts broken out of the zoo, or Zil’s animalistic behaviour. Dynamic switches in perspectives intensify the internal and external tumult, and the madness is pushed to its peak in full-page splashes packed with severed figures and sound effects sprayed across the page. At the same time, dialogues parody the distorted language of manipulation, as when Choky’s shrink uses psychoanalysis to draw out the darkest side of Zil, or when Choky cooks up schemes to conceal the plastic birds’ ugly voices with “O Sole Mio” and their rotting smell with “Operation Scent.”

Jamie Richards’s seamless translation succinctly yet perfectly captures each character’s tone and Buzzelli’s dark humour. There is much to admire in the way Richards translates jokes that play on Zil’s distorted body; for example, in a scene where Zil’s detached limbs make a woman faint, he remarks that he is “in worse shape than her” (my italics). Similarly, while he is being driven to a clinic and later examined by a doctor, he is told to “keep it together.” In one instance, Richards even adds a deft pun, transforming the psychoanalysis’s comment that Zil is “molto buffo” (very funny) into “he’s a real cutup.”

This first volume of Buzzelli’s collected works is a sensational tour de force, to be enjoyed in all its intellectual horror and in eager anticipation of the subsequent volumes.

Kafka’s Son by Szilárd Borbély, translated from the Hungarian by Ottilie Mulzet, Seagull Books, 2023

Review by Urooj, Copy Editor

For readers and scholars of literature alike, across a great number of languages, Franz Kafka is a “household” name, known for the fantastical, existential, and absurdist nature of his writing. But though both The Metamorphosis and Letters to Milena are in my possession—and I have glanced longingly at Amerika in many a bookstore—I’ve not yet read his work. Yet, the opportunity to sit down with Szilárd Borbély’s Kafka’s Son somehow felt like one that could not be missed. Having only known of Kafka’s worlds through descriptions and constant cultural references, the Hungarian writer and poet’s posthumously published book tempted me with another gleaming, unclear window, through which I could look at this infamous author.

Borbély’s book is a myriad of things—more prism than window perhaps, with each slant of refracted light throwing up fragment after fragment. The prose refuses stable meanings, and instead leans into powerful visual impressions and vignette-like imprints, resulting in a filmic quality. The book is, as the title suggests, as much about Franz Kafka as it is about his father, Hermann Kafka, and the fraught relationship between the two—but it is also about language, memory, and Eastern European politics and culture. The chapters are brief and splintered; some are composed in an epistolary format between father and son; some constitute abstracted narrations on myth, religion, or paternal relations; and some give short glimpses into Franz and Hermann’s lives, describing their childhoods or their relationship to Judaism in the third person, prefaced with: “We see Kafka. . .”, in the way of screenplay.

This visuality, a distinctive feature of the book, persists throughout Borbély’s prose and lends to its immense, near compelling readability, even if no linear narrative may be found. Each fragment is enriched with a language both dream-like and cinematic, and Ottilie Mulzet’s fluid, almost taut, tightly woven translation results in a seamless composition, with no awkward phrasing or out-of-place line to be found.

In the preface to the contents of the novel, Borbély writes:

This novel takes place in Eastern Europe. It is about journeys and those who journey. It is about the journeys of Franz Kafka, who is not identical with Franz Kafka. And about staying in one place, without which travel would lose its meaning. And about strolling, a trajectory that always doubles back upon itself. And the places that observe all of this, puzzled. They follow and accompany the one who strolls. The person who strolls along, never getting anywhere. He only gives structure to the places through his movement; he connects the places together.

In a sense, the last two sentences are a befitting description of the author in relation to the book itself; such is precisely what Borbély accomplishes in Kafka’s Son—he “gives structure” and “connects the places together,” stringing an imagined letter by Hermann Kafka to an evening walk that Franz Kafka takes, to an abstracted retelling of Oedipus Rex (alluded to as”‘Swollen Foot,” the literal meaning of Oedipus), to a very brief chapter written from the perspective of Kafka’s fiancée, Felice Bauer, and so on and so forth. The result is a mediation on changing literary forms and the ways in which we might tell or (re)imagine stories—as letters, as maxims, as vignettes told from different points of view—and also a complex exploration of mortality, faith, and familial relationships.

Borbély also supplies his text abundantly with striking, lasting bits of writing:

The father is the grave of the son.

The son is life of the father. The father is the death of the son.

With descriptions that carry both pathos and humour in a tonal irritation that any child might identify with:

His father was dead: this only increased the feeling of unpleasantness. Why doesn’t he at least have a body? Anselm K. asked himself. Every proper father has one that he wears continuously, not just sometimes, like a winter coat. . .

With beautifully abstracted notes on language and nation-state building:

He knows how to hide amid the shelves and enjoy the silence here. There’s no silence anywhere else. The dictators of Eastern Europe always wanted to drive people insane and that is why silence was nationalized; silence, one of those vestiges of the ancient world. They took it out of circulation, just like the old money with the portraits and emblems of the previous dictators.

The prism-like mosaic light of Kafka’s Son continues to dance in the mind as a result of these finely crafted sentences and impressions. In her translator’s note, Mulzet mentions that she has taken care not to make changes to his fragmented text for the sake of coherence or completion, and even if Kafka’s Son is a first draft that could not be completed due to Borbély’s untimely, tragic death in 2014, the work seems neither incomplete nor lacking. In fact, its immediacy and compelling beauty, as well as its ability to distil profundity and pathos into three-lines maxims or to narrate scenes almost as if they were unfolding before a camera, it all perhaps stems from this sense of the “incomplete.”

Reading Kafka’s Son has been very much like taking a long, beautiful, and brutal stroll with these figures: Szilárd Borbély, Franz Kafka, Hermann Kafka. Wandering through Prague at the turn of the nineteenth century, huddling in their rooms or by their desks, overhearing their conversations and their pains in fragments—it’s almost as if Borbély were remembering it all, and inviting you to do the same. One returns from such a walk almost dazed, slightly altered, turning these memories over uneasily in the head mind, the words lingering long after. Wouldn’t you want to take a walk like this too?

The infinite loop / El lazo infinito by Oneyda González, translated from the Spanish by Eduardo Aparicio, Akashic Books, 2023

Review by Nestor Gomez, Editor-at-Large for El Salvador

Who do you see in the mirror? This central question serves as the guiding thread throughout Oneyda González’s captivating poetry collection, The infinite loop / El lazo infinito. Awarded the 2022 Paz Poetry Prize from the National Poetry Series and appearing now in a bilingual edition with Eduardo Aparicio’s translation, this work offers a profound exploration of identity, history, and experimentalism. González, hailing from the historic city of Camagüey, Cuba, draws inspiration from a literary legacy that includes luminaries such as Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda, Nicolás Guillén, and Severo Sarduy—the latter proving to be a significant influence on The infinite loop and its thematic richness.

Organized into four sections—The Loop, Facing the Mirror, The Other and I, and Greek Head—comprising of eight to ten poems each, The infinite loop showcases González’s adeptness in traversing the boundaries of surrealism, whether it be in the depiction of vivid landscapes or the momentum of each line. In her introduction, Paz Poetry Prize judge Lourdes Vasquez suggests that the speaker is a woman grappling with what she sees in a mirror: the mirror of cinema, the mirror of history, the mirror of pain, the mirror detached. The resulting poems trace an attempt to recover what has been lost in the world of reflections—to embrace instead nature, life, light, and to find a space between opposites on this introspective journey. Vasquez’s introduction hints at this quest for the obscure as the speaker, identified as a woman, faces her own image in the mirror; here, the poet grapples not only with what has been lost burt also with what remains and what is found, constructing a nuanced exploration of self-identity.

The collection commences with an evocative vignette that foreshadows the poignant journey ahead: “At La Rampa cinema, after an unexpected power outage, a group of us diehards got to see a film that would transform us: Burnt by the Sun by Nikita Mikhalkov. Awarded at Cannes, and an Oscar winner some years earlier, its director had come to present it. When the screen lit up, nothing could stop the face of a young boy from my hometown from coming to mind. He was called to fight in Angola, and we never saw him again.” In its brief reminiscence, it touches on all the themes and motifs that run throughout The infinite loop: the mirror of cinema, the ghosts of those missing or dead, the presence and absence of light, and the suffering of jilted destinies. The recalling of “a young boy from my hometown” bears an eerie connection to a young man in the film, who has also disappeared after being conscripted into the military. He was thought to have disappeared, leaving behind a promising musical career and a fiancée, and the resulting emptiness and despair nearly claimed his fiancée’s life. One inevitably wonders what became of this young boy who went to fight in Angola. Whom did he leave behind? What did he believe before he left? And how will his legacy persist through the speaker’s voice in these following poems? This cinematic glimpse sets the stage for the collection’s exploration of memory, transformation, and the indelible impact of history on personal narratives.

In one of the opening poems, “Le petit déjeuner,” González delves into the complexity of desire. The speaker reflects on the silence of a teacup, laments the loss for unspecified important things, and yearns for new experiences to assuage the suffering for human longing. The repeated motif of wanting—a new dress, a rising, a song—culminates in the desire for emotion itself, the elusive chimera that offers a path forward.

If I stop, it’s fixity.

If I don’t risk it, it’s the fall,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxand one wants to rise

to rattle the dawns.

One wants to light new candles,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxplay the everlasting round

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxin a new dress

Sing a virgin song.

Carry a hibiscus flower

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxbrushing the innocent lobe

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxwith its stem.

xxxxxxxxxxAnd one wants

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxthe emotion,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxand the chimera.

The chimera, introduced by Homer as “the bane of men,” emerges as a powerful motif for the woman-identified speaker, representing a willingness to use whatever is necessary to exist, to move toward light—a focal point of exploration within González’s verses. The speaker of the poem weighs the choice between staying put and taking the risk of moving forward, “fixity” being a word associated with permanence in place while “rising” and “dawns” giving impressions of newness, forward movement, and the future. Desire is also found in this rising: the lighting new candles and a hibiscus flower—a powerful element in Santeria that represents love and good fortune.

As the reader travels through this poetic journey, González invites contemplation on the intricate layers of identity, the cyclical nature of desire, and the ever-shifting mirrors that reflect our multifaceted selves. The Infinite Loop / El Lazo Infinito stands not only as a testament to González’s literary prowess, but also as an invitation for readers to peer into their own mirrors—to unearth the chimeras that dwell within.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: