With technology perpetually advancing, questions are continuously raised about the relationship between art and computing. As artificial intelligence models gain increasing purchase, this discourse has been coming to the fore once again. The artist and researcher Winnie Soon is not interested in binary thinking about this relationship; instead, she is “interested in thinking with, and through, programming.” The discussion about art, literature, and technology often feels fraught and contentions; in this edition of our recurring series highlighting visual work from our archives, we revisit Soon’s visual feature from our January 2020 issue, which models a richer, more complex view.

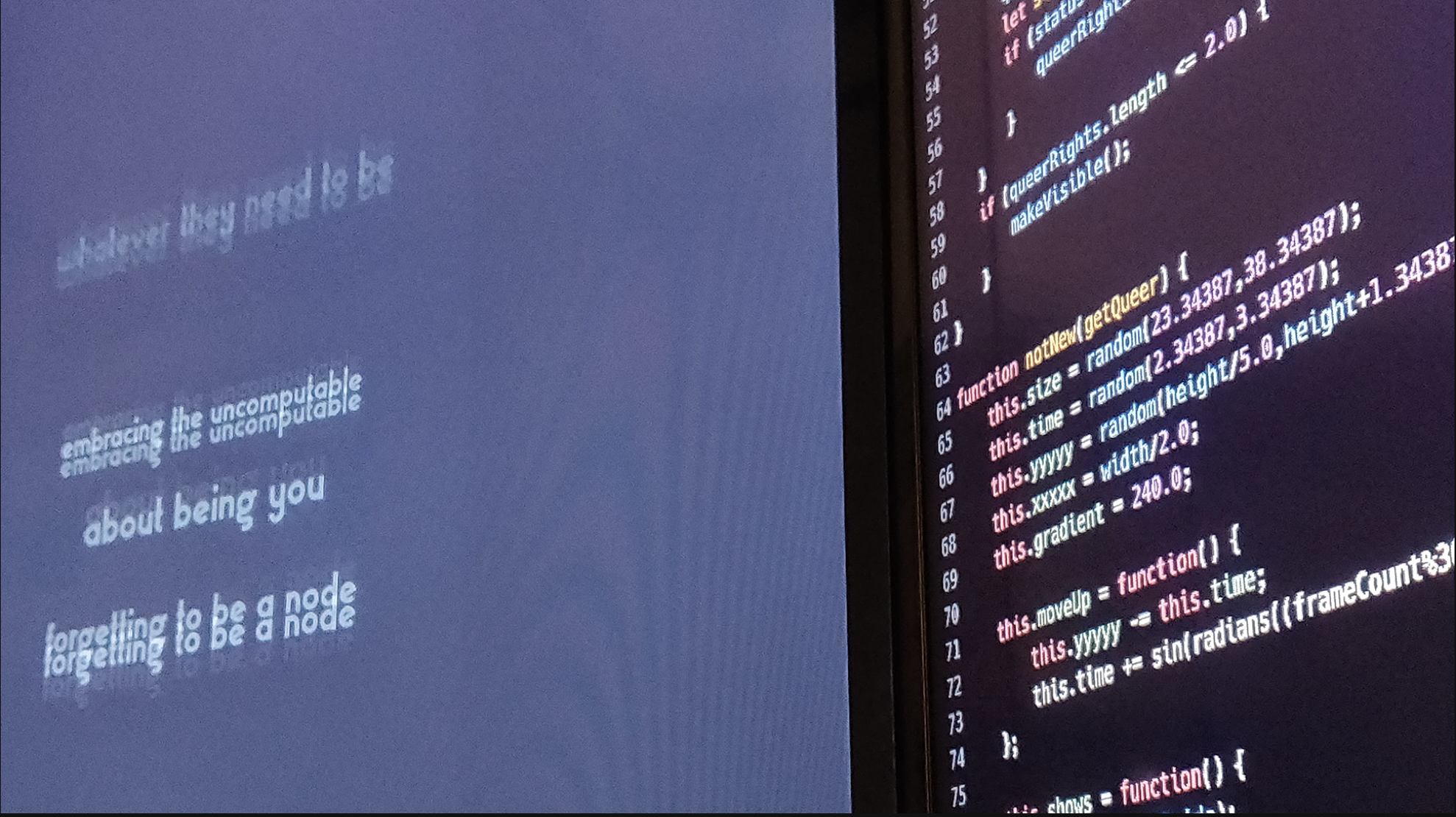

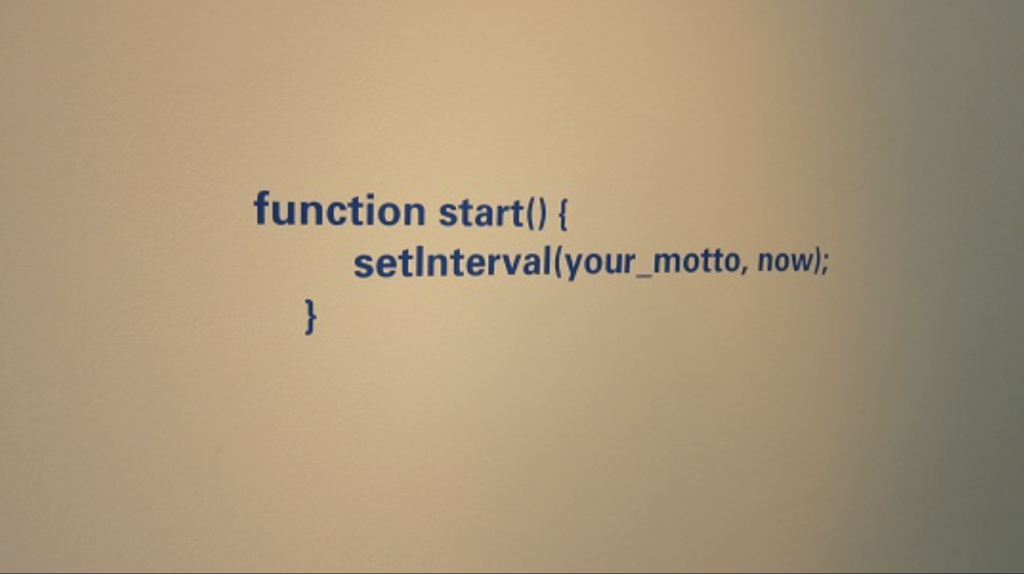

For me, the notion of queerness has to do with thinking beyond binary and normative categorization, questioning the assumptions behind such distinction. For example, some people might think that the computer is a functional tool and use it just to realize their thoughts or to achieve certain goals; or they might consider computer programming as a means to build platforms, apps, and gadgets in the neoliberal context in which we often come across these applications in contemporary culture. To invite various participants to donate their voices is a way of thinking about how we might challenge the norms of everyday practices, including computing. The project asks, what does it mean when human voices are computerized and performed within a formal logic, and how might I, as artist-programmer, play with the program code as the in-betweenness of formal logics and natural languages?

Regarding the question of living and nonliving, we are less interested in that dichotomy, but in how the body is part of the integrated human-machine system. We wanted to problematize such distinctions of machine and human, living and non-living, questioning the concept of voices in the context of digital culture. In this work, there are humans and possibly bots that are represented, translated, or even mediated, via a real-time computational process.

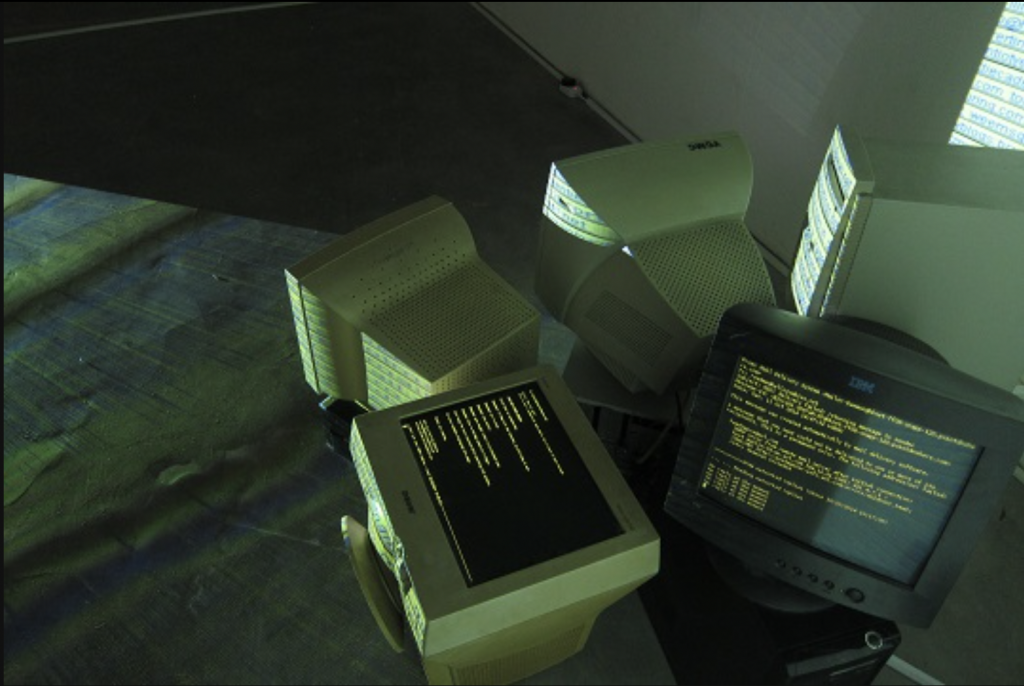

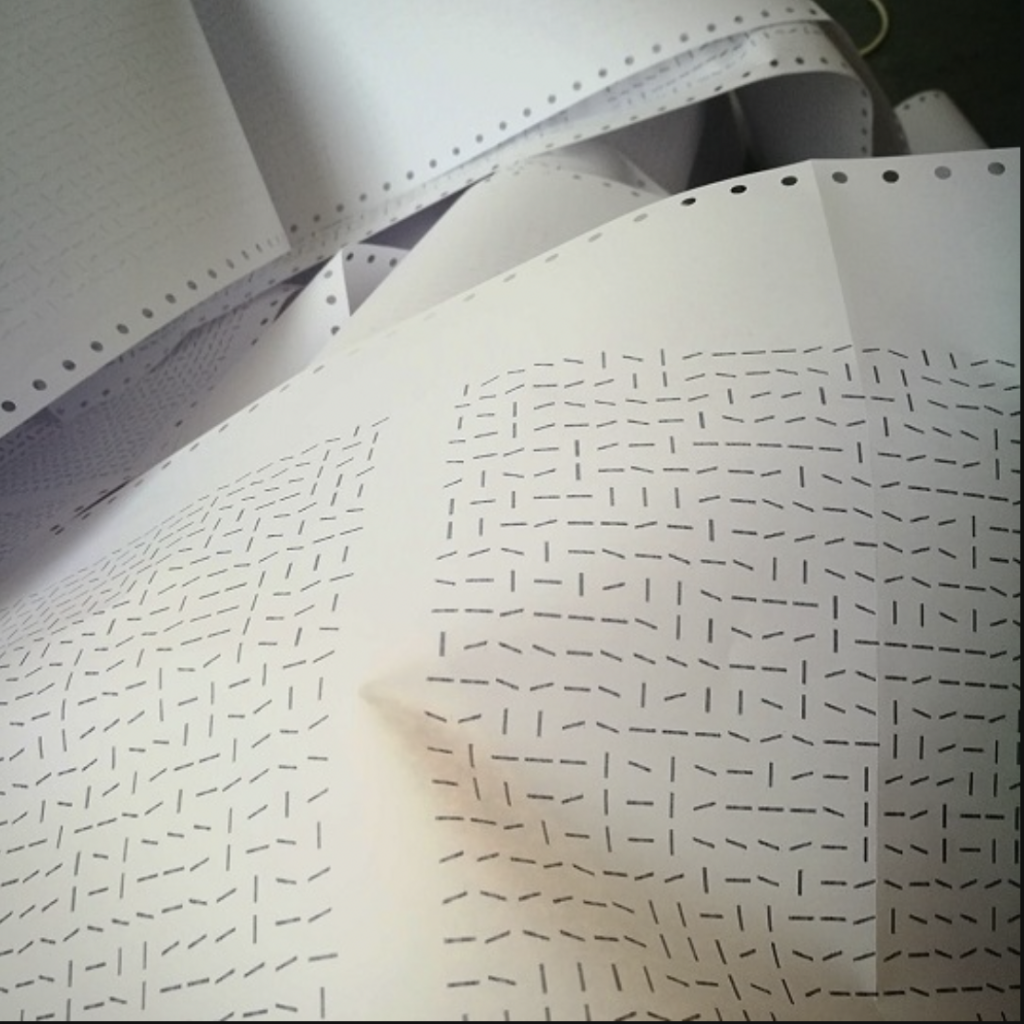

The installation, building upon the 2018 version, includes display of a screensaver, with both static characters and a computer-selected character that throbs, and a dot matrix printer that reproduces the pattern every ten minutes, showing the generative processes of how a throbber, or the overall pattern, evolves subtly over time. These pieces explore different scales of time and temporality, including spinning and generative times, machine and waiting times, processing and executing times, storing and printing times, past and present times, evolving and perpetual times, and examine how the affective nowness and perceptible realities are entangled with computational operativities.

The iconic symbol of the throbber usually indicated that micro-temporal actions are being performed behind the screens of loading, waiting, and buffering in digital culture, but we as ordinary people have no idea what is really taking place and how long we should be waiting. The now that we are immediately experiencing via streaming and displaying live data, from personal computers, smartphones, IoT devices, and among other interfaces, is essentially a delayed present with networked agencies, computational procedures, and technological operativities. From a research perspective, I am interested in the gap between presenting the unknowable time and temporal operativities that are happening beneath the screen interface, including discrete signal processing, internet data transmission, and the processes of buffering, to understand the role and implications of computational time, and how the perceivable now is being rendered by computational conditions. Indeed, the now that we experience is entangled with computational logic.

For this piece, we have collected thirty-five historical and contemporary queer and feminist manifestos that are archived online and housed in the radical bookshops and libraries in London, specifically the places around Kings Cross and Euston, sites that are historically important for the queer movement but that have been affected significantly. For example, Queer nighttime spaces have been replaced by the relentless gentrification of tech companies and start-ups.

We fed the collected manifestos into a machine learning algorithm (Recurrent Neural Networks) to generate new collective voices, which is not the usual way of using machine learning to learn a single author’s writing style. But through this process, we found a lot of new, forgotten, and interesting (misspelled) words.

Winnie Soon is an artist-researcher with a background in Information Systems and Computing (City University of Hong Kong), Media Cultures (School of Creative Media, City University of Hong Kong), and Digital Art and Technology (University of Plymouth). She has a Ph.D. in Software (Art) Practice (Aarhus University). Her projects have been presented internationally at museums, art festivals, libraries, universities, and conferences, including ZKM, RMIT Gallery, The Photographers’ Gallery, Transmediale, Electronic Literature Festival, ISEA, Roskilde Library, Image Galleri, Si Shang Art Museum, Pulse Art + Technology Festival, FutureEverything Art Exhibition, Ars Electronica, The Wrong-New Digital Art Biennale, and the Hong Kong Microwave International Media Arts Festival. Her honors include the Expanded Media Award for Network Culture at Stuttgarter Filmwinter-Festival for Expanded Media and the WRO 2019 Media Art Biennale Award. Currently, she is an assistant professor in the Department of Digital Design at Aarhus University, Denmark.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: