As Mekhitar Garabedian told Eva Heisler, Asymptote’s former Visual Editor, “[b]ecause of the contemporary political, economic, and cultural situation of Lebanon and Syria, and of the Middle East in general, these places (and their histories) are meaningful, significant, and vital presences in my daily life. Diaspora means experiencing a disseminated, shattered, divided self.” This statement suggests that diasporic identity is both a geographic and historical condition and that it is marked by both continuous felt presence and continuous literal absence. It is, in this way, a condition of both the shattering Garabedian names and one of possibility, as demonstrated in the art that comes from so many diasporas, including Garabedian’s own. In this edition of our recurring series highlighting visual work from our archives, we revisit Garabedian’s feature from our July 2015 issue.

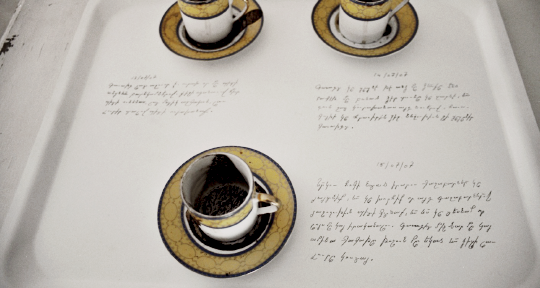

Without even leaving, we are already no longer there, 2010–2011, video installation, DVD, 3 screens, dimensions variable, 3 x 30min. Detail. With Nora Karaguezian and Laurice Karaguezian.

Cinematography by Céline Butaye and Mekhitar Garabedian.

In my research, I contemplate the conceptual possibilities of the work of art. I often use modes of repetition that reference literature, philosophy, cinema, pop culture, and the works of other visual artists—citing, replicating, and distorting references, exemplary modes, and works from art history and from my own history. I employ references as structures or elements upon which I can build, adding different layers, or contaminating them with altogether different contexts.

My interest in citation developed instinctively, probably through the experience of growing up with two languages, which engendered the feeling of always speaking with the words of others, perhaps also by encountering the early films, full of citations, of Jean-Luc Godard, at a young age, and through growing up in the nineties with the art of sampling as practiced in hip hop culture.

My use of citations or references also comes from my interest in the idea that identity is always a borrowed identity. One can never pretend to be someone out of the chain of the past. One is always speaking with the words of others. Talking with the words of others requires a library (and a dictionary) of the words of others. In my work, I use talking with the words of others and the construction of a (personal) library as a conceptual artistic strategy. My use of modes of repetition also relates to the Catastrophe; after a disaster, only thinking in ruins, in fragments, cut-outs or debris, remains possible.

Untitled (Gurgen Mahari, The World Is Alive, Venice), 2015, neon installation,

approx. 2 m x 60 cm x 5 cm.

In diaspora, both the old and the new, the original family and the new community, their languages and cultures, appear equally attractive and problematic, resulting in a subjective condition marked by longing and belonging, and by always being in between cultures, times, places—layering, contaminating, and balancing different pasts, presents, and futures—being here, and, at the same time, always already there. It means to keep feeling threatened by this past, by this former territory, and to be caught up in memory, the memory of a happiness or a disaster—both always excessive.

Diaspora is also marked by translation. Inhabiting two or more languages concurrently challenges our subjectivity, as we are pending, undecided, between two languages. Bilingual or multilingual consciousness is not the sum of two languages, but a different state of mind altogether—defined by the mode of translation. As a foreigner, you are constantly translating, in both directions. You find yourself in a position in which you can no longer speak of a mother tongue—always in between (two, or more) languages, always speaking the words of others.

Being essentially a translator, the foreigner is intimately aware of the untranslatability, and of the foreignness (or otherness), of language; the uncanny, intractable, and disturbing character of language—experiencing that we not only speak a language, but are also spoken by it.

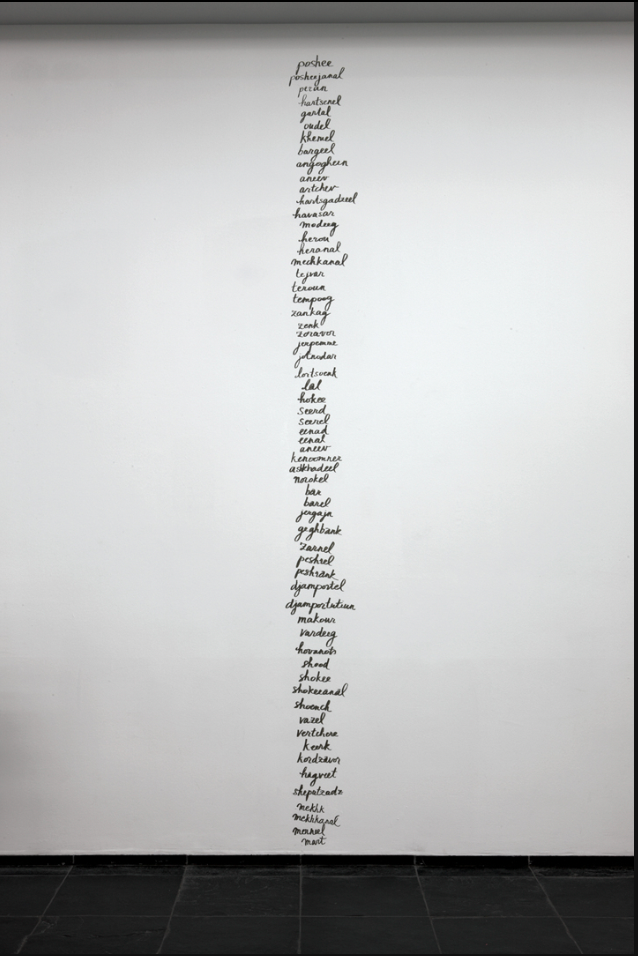

Words, Recollected, 2010-ongoing, marker on wall, dimensions variable.

I touch upon different kinds of memory in my work. One is “postmemory.” Diasporic subjectivity is marked by “postmemory”; to grow up dominated by narratives that precede your birth. Even though the Catastrophe did not take place in my lifetime, nor in that of my parents, the narratives and experience of that history had a major influence on us (with differences for each generation). These experiences were transmitted so deeply and affectively as to seem to constitute memories in their own right. To grow up with inherited memories means to be shaped, however indirectly, by fragments of events that still defy narrative reconstruction and exceed comprehension. These events happened in the past, but their effects continue into the present.

I’m interested in the dynamics between comprehension and incomprehension. I like listening to a foreign language that I completely don’t understand. I like the space of getting lost and of “not-knowing,” of deciphering. Often I position the viewer or spectator in a position of not-understanding, or within this dynamic of understanding/not-understanding. I’m not a traditional storyteller, I suppose. Every story has a beginning, middle, and end, but I don’t necessarily present these parts in chronological order.

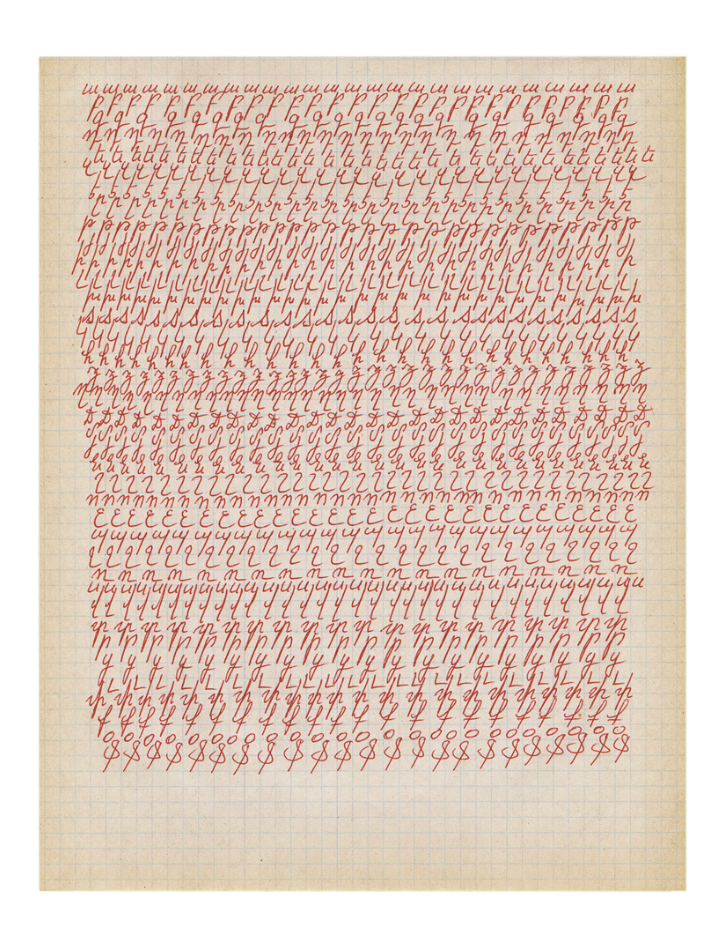

fig. a, a comme alphabet, 2009–ongoing, pencil, pen, marker on paper, dimensions variable.

Armenian is a language I was never taught, that I speak with a grammar I make up and with a limited vocabulary. I speak Armenian, but I barely read or write it, hence very few new words are added to my basic vocabulary. I only use the language with my immediate family. My Armenian is, like [Julia] Kristeva’s Bulgarian, a maternal memory. In Intimate Revolt, Kristeva writes of “this maternal memory, this warm and still speaking cadaver, a body within my body, that resonates with infrasonic vibrations and data, stifled loves and flagrant conflicts.” Exile always involves a shattering of the former body, of the old language; substituting it with another, more fragile, and which feels artificial.

Dutch is the language of my scholarly education, the language of my public (and intellectual) life, yet even when the foreigner (or diasporic subject) blends in perfectly with the host language, without forgetting the source language, the mother tongue, or only partially forgetting it, he is perceived as foreign because of this translation, which however perfect betrays a melody and a mentality that do not quite accord with the identity of the host. While aspiring to assimilate the new language absolutely, the foreigner injects it with the archaic rhythms and instinctual bases of his native idiom.

Revisit our feature on Mekhitar Garabedian and the accompanying portfolio of work here.

Images courtesy of Mikhitar Garabedian.

Mekhitar Garabedian (1977, Aleppo, Syria) lives and works in Ghent, Belgium. Garabedian’s solo exhibition Without even leaving, we are already no longer there was presented at SMAK, Ghent, in 2012, and his work has appeared in group exhibitions at the New Museum in New York, the Elba Benitez Gallery in Madrid, and, in London, at “waterside contemporary” and The Drawing Room. Current and forthcoming exhibitions include: Armenity/Hayoutioun (National Pavilion of The Republic of Armenia, Venice Biennale), Between the Pessimism of the Intellect and the Optimism of the Will (Thessaloniki Biennale), and Un bel été quand même, a solo exhibition at BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts, Brussels. Garabedian is currently affiliated with KASK/School of Arts Ghent as a researcher and guest professor of installation and media art. He is represented by Albert Baronian Gallery, Brussels.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: