The Nobel announcement this year came with particular delight to us at Asymptote, as it perfectly coincided with our Book Club partnership with Transit Books to bring you Jon Fosse’s latest offering in English, the surreal and contemplative A Shining. Written in the Norwegian author’s singular blend of contemplation and poetic prowess, the novella is a metaphysical tale of mystery given physicality, a masterful portrayal of what we’re wandering in—and what we’re wandering towards.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

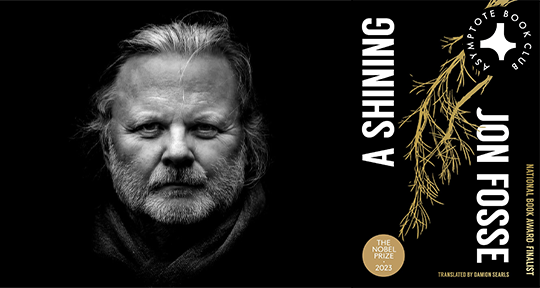

A Shining by Jon Fosse, translated from the Norwegian, Transit, 2023

On October 5, 2023, the Norwegian writer Jon Fosse was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, with the committee lauding ‘his innovative plays and prose which give voice to the unsayable’. This preoccupation with the unsayable is ever present in Fosse’s work, and in A Shining, the latest title by the author to appear in Damion Searls’ translation, it takes the form of an entity, a shimmering outline of a being, appearing to the novella’s narrator in the forest. This spiritual encounter pulses at the bounds of language, at the threshold of the divine. Recounted in Fosse’s characteristic style—rhythmic, cyclical, flowing like a cascade—the slender volume offers an introduction to its author at the height of his powers.

Long before becoming a Nobel laureate, to speak of Fosse was (and perhaps still is) to speak in hushed and reverent tones. In a piece on the ‘incantatory power’ of Fosse’s work for The Atlantic, Damion Searls shares that, after encountering a German translation, he began learning Norwegian just so that he could translate the author’s Norwegian Nynorsk—in Fosse’s words a ‘rare language’, spoken in the west of the country by roughly a tenth of the population. In a similar note of awe, literary critic Merve Emre has described Fosse’s Septology, a seven-volume, three-tome masterwork written in one long sentence, as ‘the only novel I have read that has made me believe in the reality of the divine’. But for readers who may shy away from Septology’s many pages, A Shining is perhaps a welcome alternative, as a novella that reveals a glimpse of Fosse’s singular mystery—in condensed form.

Part of Fosse’s appeal is his ability to capture the rhythms of the everyday, in his elastic prose which guides us toward the transcendent. A Shining begins:

I was taking a drive. It was nice. It felt good to be moving.

These three short sentences already communicate something about our narrator: a man who relishes movement because in some way, he is stuck. The opening pages paint a picture of anxiety and boredom, a ceaseless monologue that turns in on itself as we learn that our narrator has taken a drive, turning right then left then right and so on, until his car gets stuck at the end of a forest road. In the process of narrating this motion, Fosse paints a sensitive picture of landscapes both internal and external; the anonymous pines that evoke the fjords and the dark woods of western Norway, juxtaposed with the narrator’s turbulent mind as he ruminates over a series of ill-conceived decisions, which have led to his current predicament.

In contrast to Septology’s third-person narrator, A Shining is recounted in the first person, demonstrating Fosse’s flair for language, doubtlessly honed by his experience with theatre; the author one encounters here as a novelist is often recognised as the most produced playwright alive today, with plays translated into over fifty languages. In the novella’s sparse setting and intense attention to psychology, we sense this attentiveness to the ways of the stage. At several moments, as we experience the narrator’s indecisive and recursive thought patterns, as well as his problems of immobility, Fosse seems to evoke one of his literary influences, Samuel Beckett, and the stasis of Waiting for Godot. And just as ‘Godot’ has been read as a play on God, Fosse uses this mundane inconvenience as an opportunity to turn his attention to the mysterious, the spiritual, and the divine.

The narrator enters the forest, thinking of looking for help, yet quickly becomes lost in the darkness. As he grows cold and tired, the unexpected occurs:

I see the outline of something that looks like a person. A shining outline, getting clearer and clearer. Yes, a white outline there in the dark, right in front of me.

This tentative narration builds the tension, until we realise that we are in the midst of a surreal, spiritual encounter. The narrator is overwhelmed by this presence; he ‘can’t really talk to thin air, thin air, thin air’, and feels bound to silence. ‘[T]his prohibition was binding and unalterable, that’s how it felt’. In this moment, the narrator is quite literally awe-struck in a potent amalgam of reverence, fear, and wonder—inspired by an encounter with the heavenly or the sublime. Here we meet Fosse as a priest of the sacred, leading his readers to understand the divine’s nature. And while the author famously converted to Catholicism in 2012, this meeting with the shining transcends any single religion, speaking instead to the nature of faith.

Faith is both a monologue conducted by the believer and an imagined dialogue—a one-sided, silent conversation. A Shining, in turn, evokes the suspension of disbelief required by prayer: the act of speaking alone, without any expectation of a direct response, but rather believing that the reply will manifest itself around you—the implied dialogue of any word spoken to a god. For the sceptical, a delusion; for the believing, the sanctity of faith. Here, Fosse exposes how a dialogue with the divine would leave you speechless. What can you say to a presence whose forms you cannot understand?

Still, the author does not give voice to the unsayable for nothing, and in A Shining, we wrestle with the nature of spiritual experience. The narrator loses sight of the shining, and with the fear struck into his heart by the apparition, questions the experience. Was it a person? A ghost? An angel? This uncertainty leads him to call out:

And I say: are you there—and I hear a voice say: yes, yes, yes I’m here now, why do you ask—and I say: do you know who I am—and the voice asks why am I talking to it and I don’t know what to say,

The voice reassures with its ‘yes, yes, yes’; in the dark forest, the narrator is not alone. And as he speaks with the voice, tentatively, haltingly, it does not abandon him:

. . . and it was a thin and weak voice, and yet it’s like the voice had a kind of deep warm fullness in it, yes, it was almost, yes, as if there was something you might call love in the voice.

This is the love of God that Fosse describes: unattributed to any religion, but understood as an all-seeing, all-knowing, always present force of love. Fosse understands that this experience he recounts is beyond rational belief; it resists all efforts to restrain it into language. The narrator uses similes constantly, the ‘like’ as a crutch to attempt to put words to the divine, or he speaks tentatively: ‘something you might call love’. This struggle to find language for the divine continues to preoccupy the narrator, and as the novella progresses, the sentences get longer and longer, more and more rhythmic, until we enter into the ‘slow prose’ which characterises much of Fosse’s recent work. In this slowness, the purpose is not to labour painstakingly over every detail, but rather to marvel at them. If something is unsayable, it is because language is too pedestrian—so we must stretch it, searching out words for this experience of the beyond, even if such efforts only result in empty gestures. The shining is:

just there, yes, it sort of just is, and words like radiant, like whiteness, like shining, are sort of without any meaning, yes it’s like everything is without meaning, and like meanings, yes, meanings don’t exist anymore, because everything just sort of is, everything is meaning, and . . .

Everything is meaning, and.

Searls tenderly matches the varied rhythms of Fosse’s prose throughout, paying careful attention to the elasticity of each sentence, and matching it in an English that similarly alludes to the unsayable. Fosse has praised Searls’ translations, remarking that he ‘has the kind of ear for the music of literature that’s needed’, and thus, at its most transcendent moments, A Shining offers us a kind of music. While not wordless, the book understands that pure semantics can only get us so far, and that the melodies and rhythms of language are an alternative method to access the beautiful, to motion toward the unsayable. In this translation of A Shining, readers are granted access to Fosse’s understanding of the divine.

Georgina Fooks is a writer and translator based in England. She is the Director of Outreach at Asymptote, and her writing and translations have been published in Asymptote, The Oxonian Review, and Viceversa Magazine. She is currently completing a doctorate in Latin American literature at Oxford, specialising in Argentine poetry.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: