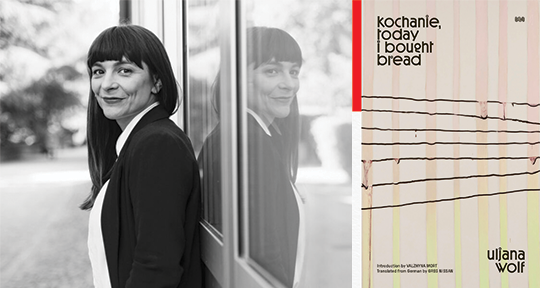

kochanie, today i bought bread by Uljana Wolf, translated from the German by Greg Nissan, World Poetry Books, 2023

In German, Uljana Wolf’s work inhabits the liminal spaces between the German and Polish languages, with all the fraught history that this double heritage involves. Now, in an English translation by Greg Nissan, this palimpsest of linguistic plurality has received another layer. Born in the German/Polish borderlands, Wolf has rapidly become a voice for a globalised, post-GDR generation, her life and work echoing the political and social upheaval of the twentieth century. In compact scenes of personal and shared experience, both dreamlike and jarring, she weaves together metaphoric word-sounds, juxtaposed imagery, and multilingualism. Nissan’s expert translations, in turn, are contemporary in the sense that they are unapologetically “unfaithful”. He has incorporated new imagery into the retold poems, such as the echoes of mink fur in “mornmink”, reiterating that his translated poems should not be seen as reproductions or ‘shadows’ of the original, but rather as a “jealous lover, eager to retort”.

Wolf’s verse is extremely dense and laden with historical and cultural references, making both the foreword by Valzhyna Mort and the afterword by Greg Nissan crucial pieces of the puzzle in beginning to decode Wolf’s poetry. This being said, such ambiguous verse is also a joy for the reader or reviewer; there are as many interpretations as there are eyes to read. The poetry benefits from its bilingual presentation, with the German on the left and the English on the right as equal partners that reflect one another without simply replicating the other. This allows readers to appreciate the form and page-feel of both languages, even if they are not bilingual.

Something that struck me initially in Wolf’s German was the formatting: a reader of German would expect the nouns to be capitalised, but here they are not. This only adds to the possibilities of their ambiguity, as words which could be both nouns and adjectives, or nouns and verbs, are no longer distinct from each other; the line einen gehorsam verzeichnen could mean, as Nissan has translated it, “to register an obedience”, but equally could have been translated as “to register (somebody/something) obediently”. The German prose is made ever denser by this use of the language, as the nouns no longer jump out on the page. While reading the German poems, I realised with a start that this is what reading English may have felt like to my German-speaking students, learning to read a language in which the nouns blend in with everything else.

Wolf’s poetry is also an exuberant confirmation of the relationship between sound and meaning. The rhythmic, almost chantlike repetitions of poems such as “sir father herr father” (der vater herr vater) play with the power of syllables, switching between the monosyllabic and two-syllable: “sir father herr father keeps his / word father keeps the word” (der vater herr vater hält wort / anhält der vater das wort). This reflects the stern, cutting tone of this short poem and elevates it into something far more complex and unsettling than the sum of its parts. On the surface, this poem looks fiendishly simple. Words such as herr (Mr/sir), vater (father), and wort (word) are repeated several times across only nine short lines, yet the result manages to succinctly represent the gatekeeping and censorship of language in authoritarian, patriarchal regimes, ending with the ominous lines “sir father herr father / treats every word / as treason” (hat der vater herr vater / noch jedes wort / für einen verrat).

In the section entitled “kochanie, today i bought bread” (kochanie ich habe brot gekauft), echoes of the Holocaust and the destruction of the Second World War jump from the page. Is the image of the “convalescent fathers” slamming the ovens shut “shovel-handed” a reference to the initial period after the war, referred to in Germany as Stunde Null (Zero Hour)? A period when the perpetrators of the atrocities “convalesced” by either exiling themselves or hiding in plain sight, slamming “all the ovens shut” by destroying or hiding as much information and documentation on Nazi atrocities as possible? Here the ovens have become a metaphor for the Shoah and the machinations of war and destruction, as well as a symbol for the juxtaposition between knowledge and ignorance, the “shovel” hands lending a blunt finality to the image.

The last two lines refer to how “the ovens slept without / collecting us in their oblivion” (schliefen die öfen ohne uns / in ihr vergessen zu nehmen); one could read this as a reference to the collective amnesia and unwillingness to revisit the crimes of the recent past, characteristic of Germany in the late 1940s and 1950s, or the policy of the fledgling GDR to scapegoat the West for most of the crimes of the Holocaust. Regardless of interpretation, however, this section of five poems is bleak and haunting, filled with palpable images of smoke, ash, tracks, and wagons—yet is also shaded by a kind of hopefulness, represented by the lyrical “we” rising “like sparks”, and the reclamation of the oven imagery for the stars: “since the stars too one says / stoke their ovens above us”. These lines reinforce the universality of human suffering and shared human experience in a world in which history seems not to be able to learn from itself. All in all, Wolf’s poetry and Nissan’s translation offer powerful commentary on the present and the past, making use not only of the words themselves, but also the spaces around and in-between them, on the page and beyond.

Anna Rumsby is an MA literary translation student at the University of East Anglia. She also teaches English as a foreign language, writes poetry and historical fiction for her blog, and volunteers for the educational arm at Asymptote. She has translated and commented on extracts from Die Zehnte Muse as part of her master’s dissertation.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: