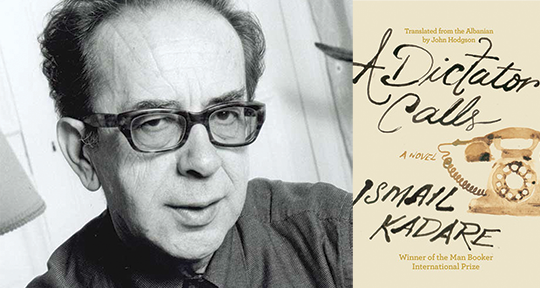

A Dictator Calls by Ismail Kadare, translated from the Albanian by John Hodgson, Counterpoint Press, 2023

In A Dictator Calls, Ismail Kadare creates an interwoven narrative of historic suspense, gently challenging the line between personal storytelling and an encyclopedic index of information. John Hodgson’s eloquent translation from Albanian is densely packed with perspectives, anecdotes, and curiosity surrounding a significant moment in Soviet literary history. How a legendary conversation transpired and what impact it had on all involved is the question that Kadare seeks to answer in A Dictator Calls; he approaches the question from all angles, and in the process investigates his own complex relationships to historical and literary legacies, afterlives, and the very act of storytelling.

Kadare’s novel is grounded in a story from 1934: Osip Mandelstam, a legendary Russophone poet, had been arrested after writing a poem critical of Joseph Stalin, a text known in English as “The Stalin Epigram” or “The Kremlin Mountaineer.” According to the general narrative, Stalin himself decided to call Boris Pasternak, a contemporary of Mandelstam’s, to ask whether or not Mandelstam was a great poet. Stories diverge, and contemporaries of both poets, from Viktor Shkhlovsky to Isaiah Berlin to Anna Akhmatova, claim different conclusions to that conversation.

Differing accounts of that strange phone call constitute the central material of Kadare’s novel. Indeed, celebrities of Russophone, Soviet-era literary history make appearances as living citations; their names are invoked alongside their alleged narrative of the infamous conversation between Pasternak and Stalin, but they are distinguished by their relationships to or conversations with Pasternak, rather than by any details of their careers and biographies. In this way, they become characters in Kadare’s formulation of this history. Kadare references an article by Izzy Vishnevetskiy as the source for the specific tellings of each individual; the passages taken from the article are introduced alongside Kadare’s enriched discussions of the famous figures and their impact on early 20th-century literary culture.

Kadare is focused on the simultaneous precision of each person’s storytelling and unknowability of the truth. What begins as an effort to clearly reconstruct the context of this conversation spirals into something much greater. The conversation becomes the jumping off point for a story that crosses borders, from Tirana to Moscow, as the narrator of the text navigates his own recollections on a long writing career. The intense interrogations of Russian history are buttressed by the narrator’s mid-career navigation of Albanian politics. While the narrator remains unnamed in the text, he has much in common with Kadare: both leave Communist Albania to study briefly at the Gorky Institute in Moscow, and both come to terms with Communist Albanian politics in order to continue writing and publishing.

Kadare’s articulations are so carefully woven that they are less like miniature essays with a scholarly bent and more like deep, intense conversations you’d have with a dear friend. The honesty and intimacy of the storytelling is rich with insight, but not oppressively dense and certainly not inaccessibly philosophical. Each telling of the conversation glides gently, introducing even upsetting ideas and images with tenderness.

The richness of reading this book in translation is undeniable. After all, Kadare’s project begins, in some fundamental way, with the act of translating Russian and Soviet biographical information into Albanian. The original Vishnevetskiy article is in Russian; the literary references appearing throughout are taken from Russian texts. Kadare weaves Soviet history and Albanian history together, translating terms from each to form a common language and story.

To give English-language readers a sense of this linguistic plurality, Hogdson often maintains the Russian quotes in Latin letters with an English translation in parenthesis. For instance, Hodgson includes a transliterated passage from Mandelstam’s “Epigram” alongside a translation into English. This artful navigation makes the many layers of translation in this piece more accessible. It gives a sense of how Kadare and Hodgson both act as translators, albeit of different texts and from different angles.

Kadare’s movement between Albanian and Soviet contexts can also be seen in his profound sympathies for and entanglements with Pasternak. The speaker’s focus on the writer begins as he introduces his “nocturnal Muscovite wanderings”, when he spends evenings recapitulating ideas, memories, and circumstances from his time studying in Soviet-era Moscow many years ago. Despite Kadare’s clear description of state-level Albanian opposition to Pasternak, the speaker finds that he is drawn again and again to Pasternak, to Peredelkino, and Moscow, and to the conversation between Pasternak and Stalin that has dominated so much myth-making in literary history from the Soviet era.

What could be an aimless exploration of the narrator’s desperate interrogation of these figures is instead a grounded reckoning with legacy and memory. From the start, Kadare cites the idea of ‘exegi momentum,’ a phrase he takes from an epigraph Pushkin used for one of his poems. Exegi momentum invokes the construction of an everlasting monument—in this case literary—and suggests the romantic potential of language to outlast the person who composes it. Through this citation, Kadare frames his meandering parallels with layers of legacy. Kadare’s attempts to seek and identify some precise historical narrative of the phone call is only the beginning of the text’s work addressing the nature of memory, with cited autobiographies, complex relationships, and post-mortem recollections also playing a central role.

The memorialization of countless writers, with an emphasis on Pasternak, is an impressive part of the book. I was most touched by the speaker’s notes on his friend, the poet Jeronims Stulpans, whose early passing cut short both the poet’s career and his friendship with the narrator. Stulpans is a voice of reason and a frequent translator, comparing Albanian and Latvian literary influences. Through his discussion of various literary movements, Stulpans pushes the narrator to contemplate fascism, history, and communism in a more direct way than any other force in the text. Yet, much like the others cited in the text, he is only a ghost, relying on the narrator’s portrayal for his continued survival.

In a text so full of ghosts, the narrator portrays both himself and Pasternak as surviving witnesses. Kadare periodically notes, while Pasternak survived beyond the end of Stalin’s rule, the stress of living under totalitarian rule and seeing his work condemned—as when the Communist Party forced him to reject the Nobel Prize in 1958 on threat of exile—and his loved ones threatened resulted in his early death. Indeed, Kadare’s novel about a threatening phone call may at first seem like a suspenseful true crime story. It is, but in its balancing of so many historic figures and their writing careers during the Soviet era, it is also a contemplation of what happens to witnesses of despotism and to those persecuted by unjust governance.

Kadare’s interest in legacy and death invites the question of who gets to tell the story of literary history and of conversations with dictators. When literature itself is at stake, who plays the role of the victim and who is the bystander has consequences for cultural output and narrative preservation. Kadare suggests that memory itself can build discourse, poetic and otherwise, with those who are no longer living.

Ultimately, the speaker’s emphasis on literature and legacy demonstrate how history has “brought the poet and the tyrant together”. Over the course of reading A Dictator Calls, I was constantly reminded of the contemporary writer’s role in preserving narratives of the past and connecting them to current events. The attempts of political forces to exert control over literature and those who produce it is not a rare phenomenon and never has been, and Kadare’s book gracefully concretizes the subject. In other words, Hodgson’s translation is being released to the public at a crucial time.

However, I hope future readers of A Dictator Calls will not stop at the more accessible and clear tellings of Russian-Soviet history; I am optimistic that the conversation between Stulpans and Kadare discussing Albanian and Latvian as “minor language[s]” will inspire further research into the histories of Albania and Latvia and other places mentioned in the text.

Early in the work, a stranger asks the speaker about “that Stalin of yours”, referring to Enver Hoxha, who led Albania for forty-one years and imprisoned and executed countless Albanians during his rule. Kadare does not expressly narrate the history of communist Albania, but his narration does allude to layers of control and power exerted by the state. Readers of the book will come to see a history of a place that is under-studied in academic contexts and of a language and literature translated much less frequently than Russian; in that way, the book becomes a powerful entryway into Kadare’s extensive oeuvre and perhaps even an inspiration to read texts by other Albanian-language authors in translation.

This is a fabulous and important read for anyone seeking a deep dive into the history of literature and the people who create it. As Kadare would likely agree, this is a book for those who “[take] the plunge in search of the truth, who [think] at first that thirteen versions is too many” and who eventually agree that the greatest pleasure, in reading, comes from the impossibility of knowing anything.

Rachel Landau is a poet and translator from Boston, Massachusetts, USA. At Asymptote, she serves as an assistant poetry editor. She is a doctoral student in Slavic Languages and Literatures at Harvard University and a 2023 ALTA Travel Fellow.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: