When Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being was published, readers lauded the Czech writer’s delicately choreographed story of individual lives pulsating through social and political forces, and soon, the book was hailed as a classic. Philip Kaufman’s adaptation, written with the acclaimed novelist and screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière, was released four years later, in 1988—despite the director admitting that he had considered the book’s “elaborate, musical structure” to be “unfilmable.” In this edition of Asymptote at the Movies, our editors take a look at the works of Kundera and Kaufman in a discussion that ranges over domestication, kitsch, and the two artists’ respective treatments of “lightness” and “weight.”

Michelle Chan Schmidt (MCS): Let’s clear the elephant out of the room; Milan Kundera famously disowned the film adaptation of The Unbearable Lightness of Being as “[having] very little to do with the spirit either of the novel or the characters in it.” In other words, Kundera felt that his novel’s “aura,” his authorial intent, was not translated well to Philip Kaufman’s screen. Much has already been said about the differences between the two works, especially in Patrick Cattrysse’s analysis of the adaptation. For one, the film elides the novel’s heterodiegetic narrative voice, instead inserting three expository intertitles at the film’s opening. It then never uses intertitles again. As such, the film’s narrative movement takes place at a distance, never immersing itself in its characters’ interior moral or emotional discontinuities. For me, this perspective erases a significant part of what makes reading The Unbearable Lightness of Being such a scintillating pleasure. The novel reads like a mirror, a commentary on the kitsch and contradictions inherent in human nature; the film reads like, well, a screen, projecting an image of kitsch without penetrating it.

The film’s chronological order also undermines that omnipresent, digressive, ironic voice, which swerves between focalizations and temporal frames to reveal the mind behind the speaker. I visualize it as a white expanse of space in which Kundera’s narrator, leaning forward on the edge of a stool behind a control panel, holds forth on the dialectics of “einmal ist keinmal.” In my view, the film opts for what we might analogize as a domesticating approach; it mechanically “reproduces” Kundera’s Czech novel in the traditional codes and modes of a Hollywood production, complete with primarily Western European actors. Kaufman’s direction untethers his film from the burdens of voice, nonlinearity, and metaphor, resigning the narrator’s ponderings on eternal return to a few hasty lines of dialogue. What does the novel’s aura, and its reproduction in the film, mean to you both? Is the film a product of lightness or of weight?

Ian Ross Singleton (IRS): I’ll start by answering your last question; I think the film is more of a weight, while the novel’s aura is, on the other hand, one of lightness. I agree with you that we can put aside a more superficial discussion of the differences between the film and novel—a friend of mine said that no film can ever reproduce a novel well, and I have to admit that any exception I can come up with is rare. It is interesting, nonetheless, to discuss, as you do, the quality of the transmutation (in the sense of Roman Jakobson’s idea of intersemiotic translation—that of verbal signs by means of a nonverbal sign system) of the novel into film.

I agree that it’s a “domestication.” Take the narrator. The film begins by focusing on Tomas, and while the film isn’t limited to his perspective, the exposition you mention is only centered on Tomas, reducing Sabina to the “only woman who understands him.” Such a framing of the narrator, this perspective, is a reduction itself, because the novel begins with a narrator discussing eternal return—a narrator who says: “Several members of my family perished in Hitler’s concentration camps.” To be fair, it’s likely impossible to transmute such a world-weary individual to film, and to say the least, the experience he describes would be rare and difficult to understand for the average viewer.

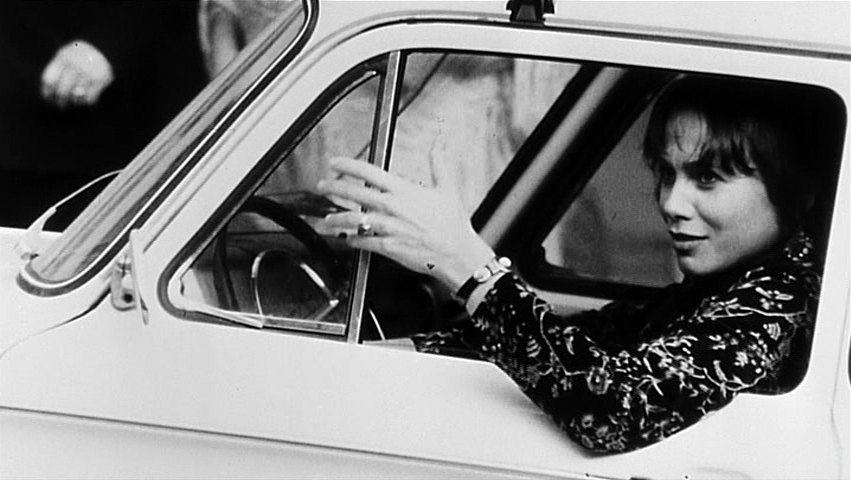

Film, as an artform, can be described by Kundera’s passage near the end of Part Two: “The camera served Tereza as both a mechanical eye through which to observe Tomas’s mistress and a veil by which to conceal her face from her.” The movie camera can serve the same dual role. Viewers can see the “crazy” Eastern European characters but remain veiled from their experience. I would love to ask Kaufman why he didn’t make more of that aspect of the novel.

In the film, this scene where Tereza photographs Sabina is recreated as more of a coming-of-age for the former—depicted not as the traumatized daughter of a nudist mother who had died quickly of cancer, but as an innocent village girl. While the latter isn’t untrue, the nuance of Tereza’s discomfort with nudity because of her mother is reduced (that term again) by the film to innocence, to a “fair” femininity. In the film, Sabina, the “bolder” and perhaps more masculine (with her bowler hat) woman, is seen as initiating innocent Tereza into a less puritanical way of being, now that they’re in the West.

This scene in the film comes near the middle, and it is the culmination of Kaufman’s use of a very standard artifact of filmic language: the mirror. The mirror is in the novel as well, and perhaps that’s why Kaufman seized on it so much. The mirror can mean sexual freedom, reflection, othering, the transfer of feelings between characters, revelation, epiphany. . . And Kaufman uses it heavily. It’s there from the very first scenes between Sabina and Tomas, there when Tereza and Tomas begin to have sex, in a shattered form once Sabina has transitioned to Switzerland, and then culminates in that photography session which becomes, for the film, a shedding of inhibition.

Here again, Kaufman is domesticating the novel. While the literal mirror doesn’t appear so ubiquitously in the novel as in the film, the novel is constantly redoubling itself through inversions and reflections—through paradox. For me, the novel seems like the work of a mind steeped in dialectical materialism, which has perhaps rejected the theory but has nonetheless invited the reader to entertain the rejection. How can a filmmaker create a work that does the same? I’m not sure. Perhaps it would be something resembling Bertolt Brecht’s Verfremdung (distancing) effect? The film has an impossible task. However, I agree that it was not necessary to domesticate the novel.

What other transmutations from the book did you find to have agreed or disagreed with the idea of Kaufman’s domestication?

Rachel Stanyon (RS): Kaufman’s film strikes me as an example of domestication masquerading as foreignization: it is a mirror held up to Czech history and politics that reflects solely its all-too-male Hollywood gaze. The US production keeps trying to convince us it is echt: for example, we have the not-yet-Hollywood-famous European actors Daniel Day-Lewis, Juliette Binoche, and Lena Olin (none of whom are Czech or even Central European) speaking in exaggerated Czech accents as if proclaiming: “This is not America!” The skill of these actors and their voice coaches notwithstanding, this, for me, served as a reminder of the film’s artifice (the characters are speaking in English for my benefit, not their own communication); it functions not, however, as the kind of conscious, exploratory interruption introduced by the narrator’s mediation on fictionality in the novel, but rather as a clumsy reproduction of “Western” stereotypes about (Eastern) European speech patterns.

Similarly, Kaufman’s insertion of archival footage from the 1968 demonstrations, shot by the Czech filmmaker Jan Nemec, could be viewed as an act of foreignization, as it not only shapes the film’s visual language but actually gives direct voice—or rather, image—to its “source.” However, it feels both labored and farcical once interspersed with imitation footage inserting Tomas and Tereza into the scene. Although the film (perhaps inevitably for anything that is an adaptation rather than a “staging” or “production”) relays just a few strands from the book, eliminating much of the plot and perspective, it is still slow, and this scene particularly long. It turns Kundera’s inextricable anchoring of the personal in its intrinsic political backdrop into what, in the film, feels like an extrinsic US obsession with anti-communism, a performance of commitment to demonstration. I entirely agree with you, Michelle, that, having been stripped of the multiple perspectives, the interior monologues, and the distanced, uncertain narrator, and also because it lingers on, or leers at, even, in the case of Tomas and his women, and celebrates rather than questions, the film itself comes off as kitsch.

MCS: I really love what you just said there, Rachel, about the “mirrored” movement of false foreignization from the intrinsic to the extrinsic, and the links you made, Ian, to intersemiotic translation and Brecht’s Verfremdung. Thank you for bringing up The Unbearable Lightness of Being’s discussion of the camera as a “mechanical eye” and a “veil.”

I did wonder how Kaufman might have transmuted Kundera’s narrator to film. I lit on a much more recent film—also a large Hollywood production set in Central Europe that adapts, though much more covertly, a twentieth-century Central European writer’s work: Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). Anderson abstracts his filmic narrator from the main plotline by a jump in time and multiple metaphysical levels, which might, as a device, come closest to transmuting Kundera’s narrator to the screen. Both speakers are “authors”; in The Grand Budapest Hotel, the narrator identifies himself as such, whereas in the novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Kundera’s narrator emphasizes Tomas and Tereza’s fictionality as inventions of his imagination: “The characters in my novels are my own unrealized possibilities. . .” They serve as eye and veil, themselves ironic byproducts of the fictional form. The authorial distance between the spectator/reader and the characters ties back nicely to the Vermfremdung effect: the alienation that the reader experiences with regard to Tomas and Tereza’s experiences. While we do come to project compassion for them through the prism of the narrator, our empathy remains intellectual, estranged at an altitude from Tomas and Tereza’s sufferings. The film adaptation of The Unbearable Lightness of Being completely reduces the authorial-narratorial distance by emphasizing the Tomas-centred exposition and the extrinsic “image” of the characters, as you both say above.

Of course, presenting Kundera’s narrator using Anderson’s technique would pose its own problems. How would a filmmaker represent him? If incarnated by an actor, does his face resemble Kundera’s? Does he exist only as a voiceover? Does he speak, as Rachel points out, in a kitsch Czech-accented English, or in Czech, or perhaps even in French, given that Kundera was exiled to France at the time of the novel’s publication, and that it was first published in its French translation? These nuances surpass the realm of this conversation, but I’d love to hear what you’d think of this narratorial device.

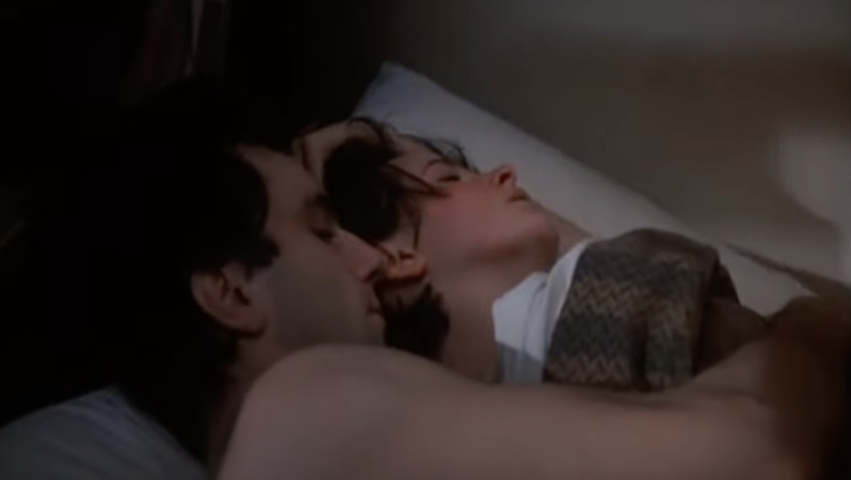

To return to Kaufman’s domestication: there is a moment original to the film, about two-fifths in, that I love. Tomas soothes Tereza to sleep after she suffers the nightmare of watching Tomas and Sabina make love in Sabina’s studio. Day-Lewis’ Tomas whispers a poem to her, a lullaby, that Kundera wrote specifically for the film: “Like a baby bird. Like a broom among brooms, in a broom closet. Like a tiny parrot. Like a whistle. Like a little song. A song sung by a forest within a forest a thousand years ago.” It’s an intimate, slow crop on Tereza’s slumbering face — a gorgeous cinematic moment — yet its very existence is a product of Kaufman’s domestication of the novel. By erasing the narratorial voice and the glide in and out of Tomas’s intrinsic interior, Kaufman is forced to resort to this method for demonstrating Tomas’s love—his attachment to Tereza beyond the sexual. The beauty dissolves into the kitsch. I’m not as certain as you are, Ian, that the film indicates weight, but I’ll reserve judgment as we continue the conversation. In the meantime, are there any aspects of the film that you enjoyed in spite of its domestication, or its foreignization masquerade?

IRS: I’m going to attempt to move backward through your comments, Michelle, and into Rachel’s too. When I say “weight,” I’m still using the word as I think Kundera presents it in the novel: as burdensome. In a sense, it’s baggage. Of course, Kundera’s narrator subjects it to his intellectual ponderance and can contradict himself, so I’m also trying to be careful here.

That care and consideration of Kundera’s narrator’s dialectical materialism in the novel is what I find to be missing from the film. Perhaps Anderson could have better depicted such a narrator, that seems like a likely possibility (and The Grand Budapest Hotel is excellent in capturing the tone of Stefan Zweig). But here is where it sounds to me again that it is important for an artist, such as Brecht or somebody with an interest in artistic depiction to at least address dialectical materialism.

In a more concrete sense, I want to discuss what Rachel points out as “an extrinsic US obsession with anti-communism, a performance of commitment to demonstration.” I was so glad to read that because it’s an aspect of the film that I also wanted to discuss. That footage from Nemec, infiltrated by images of Binoche’s Tereza and Day-Lewis’ Tomas, does show this obsession—one that I think corrupts Kaufman’s own artistic vision. But the film doesn’t show Sabina’s distaste for any kind of demonstration. Indeed, Sabina generalizes about all such demonstrations as “the image of that evil,” formed by “a parade of people marching by with raised fists and shouting identical syllables in unison.” For me, thinking of the people I’ve known from the Soviet world, this language rings true as a general refusal of any form of political activism, even if it’s anti-Communist. Rachel’s comment describes how Kaufman co-opts Kundera’s experience to make something like a slogan, but Kundera, while of course having become anti-Communist in his exile, is still writing a narrator who has experience in that part of the world. Forgive me for risking too fine a point, but I hear this language reflected in even an obituary for Kundera, which had described Tomas as a “philanderer.” While one would hope that a reader of that obituary would continue reading to understand how this feature of Tomas’ character is only part of a more complex character, I think that many in the West similarly reduce Kundera and his characters to the aspects of their personalities which serve some kind of political obsession, such as anti-communism.

Perhaps this reduction, or domestication, explains the lullaby. While I agree that it is a beautiful scene, it doesn’t ring true to the Tomas or perhaps to the Tereza I know. Their love appears to have to do with another obsession, one with each other, and one that ends up being dangerous for both of them. Tomas simply can’t rid his feelings for Tereza, so he returns to Prague and becomes trapped. He is not necessarily an anti-Communist hero, simply a person in a very difficult situation. Likewise, Tereza is more than a simple country girl; she is a patriot, and her love for her country spells her doom.

To return to that final question of Michelle’s, I think that there are many scenes that are beautiful and moving, like that lullaby scene, and like the ending and the moment Tereza crosses the room to Tomas, when they’re dancing despite their impending death, which the viewer ironically knows while they remain unaware. It could be seen as capturing some of the paradoxical and contradictory beauty of the novel, but it’s also Kaufman’s own achievement, perhaps. Do you think we can attribute that filmic beauty to Kaufman?

RS: I’m sorry to say—and also sorry to partly sidestep your question—that there was not much about the film that I found beautiful. Perhaps one exception is Kaufman’s direction of Binoche as Tereza. I did really love the way the film translates Tomas’s depiction of Tereza being like a baby in the bulrushes into Binoche’s childlike, naïve nervousness, and how her “weightiness” is clearly not just due to obsession and depression but passion and conviction—even if, as she learns, these can be repurposed as weapons. Given that Tereza’s artistic and political medium is a visual one, it makes sense that the film would be able to show so poignantly how her photographs of protest are used as evidence against the protestors. I feel that the other characters, and particularly Day-Lewis’, were made more one-dimensional by Kaufman; beyond just being a philanderer, Tomas seems to become a predator in the film.

I tried hard not to let my admiration for the novel predetermine my opinion of the film; I tried to like Kaufman’s adaptation, or even to feel neutral about it. But I found any interesting and aesthetically absorbing moments overwhelmingly overshadowed by its heavy-handedness. In this sense—which is certainly not Kundera’s—I agree with Ian that the film has “weight.” I’m not sure I agree, though, that the novel so simply equates weight with negativity and lightness with positivity; in fact, I feel that more than merely equivocating over it, Kundera seeks to upset this binary, and, if anything, perhaps ultimately puts more stock in weight: “The heavier the burden, the closer our lives come to the earth, the more real and truthful they become. Conversely, the absolute absence of burden causes man to be lighter than air, to soar into heights, take leave of the earth and his earthly being, and become only half real, his movements as free as they are insignificant.” In this sense, I would say that the novel is heavy—important, full of depth, worth returning to—while the film is light, forgettable and insignificant. But—returning at an obtuse angle to Michelle’s reference of the novel’s history and circulation (which I think also begs the unanswerable question, wrapped up in the one around foreignization versus domestication, of who the book was originally addressing)—perhaps the film, like the interlingual translations of the novel, help to add weight in their canonizing power.

Then again, perhaps the point is not so much that either “weight” or “lightness” should be privileged, but rather that pure return is suffocating and, conversely, some degree of repetition and connection unavoidable. Sabina’s and Tomas’s apparent lightness—their lack of attachment—brings them no more happiness than Teresa’s “heaviness,” and is, moreover, impossible to imagine being sustained over a lifetime, even in these explicitly fictional characters. Tomas’s return to Prague may seem a submission to weight, but he is not so much “weighed down” by his love for Tereza as he is provided with an anchor, around which the rest of his existence can more happily drift. Sabina continues to cast off baggage, but in the novel (more so than in the film), we see how her betrayals become a pattern which she lugs around. While the film shows only a glimpse of what seems to be a happy cosmopolitan existence, interrupted briefly by a flash of sadness at the news of Tomas’ death, we know that in the novel, Sabina’s thoughts often return to both Tomas and Franz (whom the film almost erases, while making Sabina barely more than a sex symbol), and that in refusing to return to Prague or Switzerland physically, in enacting the idea that a life is lived only once by trying never to do a single thing twice, she is still not entirely free: her lightness transforms into the weight of regret, which means she is a full person who actually feels things.

Without even attempting to portray the disjunction between the internal and the external, it is very hard for the film to explore this—I hope it doesn’t feel burdensome to others to keep returning to this point we’ve all already made, because I think it’s really crucial to the novel: the difference between the internal and the external, the difference that perspective can make (which is why I think Kundera retells various events and interactions), the space between the binaries. I’m not saying that other films cannot and do not also explore these issues in their own ways, but the way in which this particular work does so—through multiple perspectives, philosophical musings, and meta-fictional interjections—is perhaps easier to explore in its original medium, literature, where it is more acceptable to be genre-fluid and experimental, than in (mainstream) film-making; or at least, easier in a three hundred-page book than in a three-hour movie that needed to pay for its actors and production.

MCS: Those are all fantastic points, and Rachel, I’m so glad you mentioned the novel’s ambiguity in its dialectical materialism and its moral values of weight and lightness. That was, for me, crucial to understanding the film, which I also perceived as light and insignificant. Perhaps it’s for the best that life is only lived once if it means that the film will only be produced once, and from Kaufman’s singular perspective.

To come back to Ian’s question on filmic beauty, I don’t believe that it surpasses in any way the novel’s beauty. The elegiac tone of Part Seven is particularly heart-wrenching for me, when the novel’s impending ending—and therefore Tomas and Tereza’s deaths—impinge increasingly on the reader’s consciousness. Ian, you cite specifically the scene of Tereza crossing the room to Tomas; I think of Karenin’s death and burial in the garden, and the tensions between Tomas and Tereza as Karenin fades away from life. I don’t perceive Kaufman’s work as anything more substantial than (to come back to the point about Jakobson’s transmutation) a translation of Kundera’s story from a verbal language to an image-based language. Of course, I refuse to generalize all film adaptations under this umbrella of transmutation, but as Rachel discussed, Kaufman (or the film medium) is unable to adequately represent or transfer the novel’s qualities into image, sound, and pure dialogue (which the film is short on anyway).

For one, I was quite disappointed that Kaufman significantly cut the narrator’s musings, through the prism of Tomas, on Sophocles Rex in a Communist context. If integrated well, this might have served Kaufman’s ends of performing anti-communism for a mainstream, late-1980s American audience. A few close-up shots of the play in its book form, as Tomas pries his hand out of Tereza’s in her sleep and as Tereza visits the engineer, wink to the knowing reader, performing the service of echoing Kundera’s novel without accumulating any depth nor weight. I also felt that Franz’s storyline was unjustly cut. The film, ultimately, sinks into the unbearable lightness of watching.

IRS: Yes, I think we’re coming full circle here, but with a good frame with which to view the film. While generally, Jakobson’s transmutation is very difficult to pull off with film, it is possible to do more with it than Kaufman did. I agree that the film is unbearable in a negative sense as well as too light, also in a negative sense, for the weight of such characters and situations as the novel depicts. While Tomas perhaps does become a predator on screen—I think now of how the book has him say, “Strip!” instead of “Take off your clothes” as he does in the film—I’m not sure that Kaufman is being very critical of this aspect of Tomas’ character. I almost wonder if the film is quietly fulfilling a Western sexual fantasy of the “crazy” Eastern European woman through Tomas and the various scenes of both Sabina and Tereza. In that sense, the use of the word “philanderer” is almost done with a wink before discussions of Western feminist critiques of Kundera’s work.

Since it’s clear that Kundera is doing more complicated and sophisticated work in a medium that gives access to multiple perspectives more handily than film does, I think we’ve correctly applied his perspective to the film—which is definitively not attempting to depict dialectical materialism. The film is burdensome in that it carries the weight and attachment to becoming somewhat subtle anti-communist propaganda, while Kundera would say that weight is Tereza’s difficult mother and how she haunts this character; Tomas’ inability to flee the life he unwillingly fostered with Tereza in Prague even after the 1968 takeover; and Sabina’s recognition that one can never flee themselves. The film also, perhaps unwittingly, is (too) light by reducing Tomas’ promiscuity while failing to investigate it as the book does, and also by depicting him as a soaring anti-communist hero rather than a hesitant, overthinking anti-hero; it also fails to show how Sabina’s anti-communism is truly an anti-_____ism, in that her character, in a privileged Western way, fails to commit to any kind of political cause or any kind of side in the Cold War. That resolution remains an unachievable goal, at least in the novel.

Michelle Chan Schmidt is an assistant editor of fiction for Asymptote. She studies English literature and history at Trinity College Dublin, where she also edits for various student publications. Her research interest is in literary and historical representations of Hong Kong in Hongkongese and global culture. Her criticism and essays have been published in Cha: An Asian Literary Journal and Asymptote. She updates about her writing here.

Ian Ross Singleton is a writer of fiction and criticism and a translator of Russian and Ukrainian literature. He teaches Writing and Critical Inquiry at SUNY Albany and serves as the Nonfiction Editor of Asymptote. His debut novel Two Big Differences, about the Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity, came out in 2021 and can be found at 2bigdifferences.page

Rachel Stanyon is a translator from German into English and a senior copyeditor with Asymptote. She holds a master’s in translation and in 2016 won a place in the New Books in German Emerging Translators Programme. Her first full-length non-fiction translation has recently been published with Scribe.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: