Lojman is a book that shows its teeth. In powerful, unflinching prose of malevolence and confinement, Ebru Ojen depicts the family unit as a condition in which the most abject of cruelties and annihilations are imagined, resulting in an unparalleled portrait of madness and oblivion. By pushing her characters to mental precipices, the author points us toward the emotional peaks of human existence, drawing blood in an open display of intense, battered aliveness.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

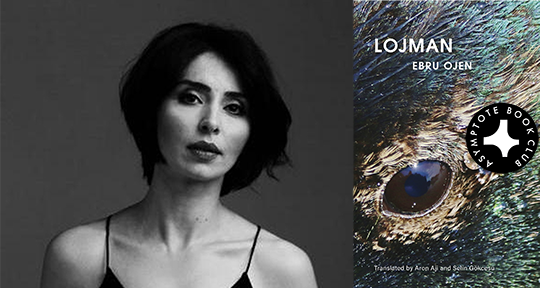

Lojman by Ebru Ojen, translated by Aron Aji and Selin Gökçesu, City Lights, 2023

There’s something out there. Such are the familiar words that announce fear’s dramatic incarnations—a sudden violent churning along the horizon, a scream that shears the night-fabric, a figure separating itself from the darkness. The common portrait of horror is aiming its heavy steps towards us, drawing nearer with each quickened breath—a grasp, a suffocation, a descent inevitable as gravity, an opaque force and singular direction. We’ve all been stranded in this lingering vastness, certain of some unbearable thing that approaches, and yet this dreadful knowledge, of what may lie out there, is only an elementary stage in fear’s true theatre. Eventually, one finds a more intolerable, more defiling fact: something that does not pursue, does not invade—something that does not come scratching at our windows, but dwells already in the closest, most secret part of us, capable of everything and knowing nothing of order, nothing of control.

Ebru Ojen’s Lojman is a horror of intimacies. In brutal, visceral treads, it walks that demarcation separating the inside from the outside, revealing all that rages against walls both visible and invisible—the unspeakable violence of the precipice. And while the outside still holds the unknowable chill of our darkest suspicions, in Lojman, it is the inside where monsters are unleashed. The title, transliterated from the Turkish word for lodging, is the first indication of this novel’s form—as tightly fortified as architecture, and as taut and enigmatic as the human body. Through passages of incandescent maleficence and enthralled terror, we are led into the stifling, worldly containers that somehow manage to hold utterly uncontainable things—all that goes on in a house, all that goes on in a mind. We have been made so small in order to live, and that unbearable reality is given, here, for writing to bear.

Taking place in a remote Kurdish village in eastern Turkey, along the banks of the country’s largest lake, Lojman grows from the corners of a single family home, tracing and searching along the tumultuous lives rampaging within. Selma, the mother, has just given birth. Her eldest daughter, Görkem, is unloved and unloving, fermenting in her small body an immense cacophony. The younger boy, Murat, is little more than another baleful mouth to feed. The newborn is never given a name. Between these four individuals is charted a gradually tightening geometry of domesticity’s blackest repressions, calculated in deranged fantasies and occasional outbursts that give way to neither solace nor compassion—such is what proliferates from the rabid desire for freedom, for something—anything—to rescue the mind from boredom’s rotted depths. Home, in Ojen’s unsparing portrayal, is nothing more than an inconsolable space where the mingling perpetrations of rage, resentment, and hatred swarm, like devoted disciples to abjection, over the helpless corpse of family.

The story begins with a departure. As winter wrecks oblivion upon the Erciş Plateau, the house is thrown into despair by both the indomitable weather and the man who has stridden out into it, never to return. Selma, left without the father of her children, heaves from her contractions alone, and the borders of the home, having freed at least one inhabitant to the greater elapse, draws the people who remain more deeply into its merciless limits:

The swelling had cracked Selma’s skin here and there, turning her legs into hunks of diseased flesh. Görkem shuddered when her toes felt the warm, foul-smelling fluid that trickled from Selma’s loins. She suppressed a gruesome groan of pleasure.

It is the low days of December, and a snowstorm stifles the village, dulling its shapes in a white siege. Neither the doors nor the windows can be opened, and as the body-horror of the birth passes and a damp, contaminated sorrow besets the family, radical dissonances of imagination and reality begin to tangle within the narrow confines. In sharp excavations of the two central female characters, Selma and Görkem, and their depraved regard of one another, Lojman details the clawing impressions that misery makes as it is expelled into an uncompromising world. Much of the book takes place within the hard, focused glint behind these two sets of eyes as they look at the objects and phantoms of their lives, at the ravages of domestication, at their own, sinister sadness. Both feel filthy in the roles assigned to them, and as such, they are as claustrophobic in the rooms as they are in their own bodies, wrecked by expectation, by the lifelessness of life, by the endless procession of time that only brings the same tired revolutions.

Weather. Hunger. The kitchen needs cleaning. The fire demands to be stoked. The infant screams for the breast. Selma, torn through from childbirth, is terrorised by the all-consuming reality of a self lost to motherhood, and everything that meets her sightline, from the baby to the teapot, is implicated in her exhausted struggle to balance herself on the precipice of annihilation:

Finally, her gaze settled on the little pool of water that had formed around the teapot. This tiny lake had so neatly marked its borders as it swelled; it was as lively and bright as the lush spring leaves that would fall and rot in autumn. She was taken by a desire to destroy that perfect ring that resisted the lethargy of everything else on the table, to smudge it all over the surface with her finger, to obliterate it.

Görkem is perhaps Selma’s younger counterpart—though both deny any similarity between them. She hovers in that uncertain period before adolescence, but her desires and piercing judgments speak of something more eternal—an almost mystical desire to destroy, the way a thoughtless god would rid an entire continent of pestilence. It is as if the birth-act were a condemnation to the same shameful life, some hollow of oblivion that passes through a woman into her daughter. Though the young girl glows on occasion with a precious curiosity and longing, her perceptions ultimately unsettle with merciless contempt. A great many objects and persons come into her mercurial purview, but it is most often Selma whom her daughter’s eyes dissect; she is documented in the throes of manic-depressive episodes, her actions rife with strange artifice and disassociations. The mother’s inability to display any warmth, her overwhelming dread at being needed in this way—none of it goes unseen by Görkem, increasingly disgusted by this ugliness. “She could see into the weakest regions of Selma’s soul.” She dreams of tearing it apart.

Still, even as these tensions continue to grow in grotesque explications, some warped balancing act is maintained between mother and daughter—a portentous, psychological war in which they remain inseparable, congealed by codependency and mutual blame. Over and over, they find the most detestable aspects of themselves in one another. Selma has the epiphany: “Her children were parasites!” A few pages later, Görkem’s lustful fantasy for a young teacher spirals into a cannibalistic mirage: “She had depleted him, transformed him, extinguished him.” Selma is suddenly struck with the urge to murder her newborn, and Görkem wants to “grab a knife and cut Selma into pieces.” Upon this Oedipal tightrope, the two have nowhere else to go. They approach each other and retract, attacking in expansive ideations of violence that are utterly antithetical to the small room they’re bound within. And ultimately it is this—the unwavering understanding that their miserable lives are utterly insignificant against the grand tableaux of the mountains, the soldiering lake, the great plains—that continues to taunt the two, keeping them acrobatic upon their degradation, seething and alive.

When Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night was first published, critics recoiled at its unflinching nihilism. In a review for L’Humanité, Paul Nizan wrote: “There is nothing but baseness and rot in this work, the march towards death with a handful of divertissements. . . Céline, in this novel of despair, sees no way out other than death. We can barely glimpse the first rays of a hope that might yet grow.” A similar sickness haunts in Lojman, where the most terrible thoughts are given matter. Page after page, we find revolts of agony. But just as Journey ultimately rests in the literary canon as a work that reveals the undeniable inhumanity seeping into the deposits of our reality, the bitterness in Lojman also carries a fearsome truth of modern existence. The novel presents, with surgical clarity, an incoherence in our domestic orders that have sentenced so many to silence and desperation. In Lojman, each searing cry, each hateful gaze, and each sadistic dream is a marker of the many small deaths that shred the self, as it is shackled to the iron roles and definitions society hands us over to.

For it’s as the author herself tells us: “And so here it is, another agonizing scene exalted before our eyes. Such scenes are always full of pain and heartbreak, and their beauty, at its core, belongs to nature’s nightmarish darkness.” In this portrait of individuals who succumb so easily, so often, to the inhuman, Ojen pulls the thin wires of humanity back into the vast network of natural beings, drawing us forcefully closer to our animality—all that modernity has shuttered into the abyss. Sifted from the patterns of acceptable behaviour, mother and child are reduced to a system of needs. There is no sacrifice, no sacred icon of divine selflessness, no glory. A being is carried into this world, and to survive it, she must carve away at the vessel that brought her here. In bringing this idea to narrative fact, Lojman tests the limits of our thinking, our tolerance for savagery, all to probe at what we have failed to articulate, time and time again, about family, motherhood, and being born. The result is this legacy of inconsolable questions—of where one life gives in to another life, of what truly binds us to one another, of love in its disappearances and re-apparitions.

To consider the possibility that we have never transcended our instincts and basest drives—such is how we can begin to understand why there exists something in us, a fury or an appetite, that drags us ever toward the unrecognisable. How we bring the depths to the surface, how we search our inner chambers for what consumes us.

In the book’s late, second act, which turns towards a genuinely shocking, phantasmic, physical manifestation of the inside-outside dichotomy, the safeguards around the family’s psychic torment finally break. All along, there has been a mastery in how Ojen disintegrates the binaries: birth and death, pleasure and pain, the primal and the civilised. But here, the prose erupts in sheer, lyrical vertigo, translated with glorious precision and abandon by Aron Aji and Selin Gökçesu, and through it we are finally swallowed whole into an experience that has no contours, no definitions—only an insatiable wholeness. Abjection, as Julia Kristeva said, is “the other facet of religious, moral, and ideological codes on which rest the sleep of individuals and the breathing spells of societies.” Buried beneath the structures of our public and private realities is a vast realm of unspoken madness, a proliferation of unanswerable questions that nonetheless erupt, constantly and with tremendous outrage, into our ordinary days. We are all touched by the ravages of this unconsciousness, for we have all been at the mercy of definitions; we have felt ourselves boiling against them, rejecting the warped mirrors the world has put up for us, and we have reckoned with what it means to live.

Throughout Lojman, the heart beats. It pounds, never still. Even in the deepest recesses there is no escaping that overwhelming rhythm. Ojen writes along the pulse, and everything she describes is powered by the thrashing motions of something holding on to life. There is a placidity and stillness that weaves through moments of bliss—serenity. But in the pursuit of survival, when trying to rescue oneself from being obliterated at the borders, nothing can be at rest. In these short, bursting chapters, these catastrophic ruptures of well-worn patterns, one senses all the vast ranges of feeling, the heights of phenomenal experience. There’s an exhilaration usually found in the sublime, in the moments of glorious beauty which move us by offering a glimpse of something boundless, capturing and losing our thinking—but see, even if you don’t want to look, it’s there in the darkness, too.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet, translator, and editor. shellyshan.com

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: