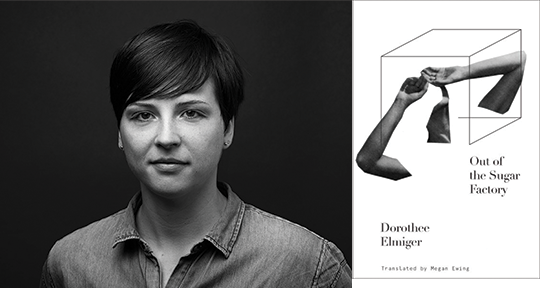

Out of the Sugar Factory by Dorothee Elmiger, translated from the German by Megan Ewing, Two Lines Press, 2023

How do you write about a book that is itself concerned with what it is about; that covers a vast array of seemingly disparate but fundamentally deeply interconnected topics in a fragmentary, multi-genre, looping montage; that is both tentative and unashamedly demanding; that is hyper-meta yet written in language that is refreshingly unselfconscious; that is so preoccupied with form and origins that it defiantly eludes attempts at endings? What can you say a book that has already said so much about itself?

You could say that, fundamentally, Out of the Sugar Factory is about exactly what its title suggests: sugar and production. In thinking and trying to write about this book, though, such a statement seems entirely insufficient—for this text, with tales spanning from the 16th century to the present day, is equally about love, desire, slavery, capitalism, the art of writing, artifice, self-representation, subjection, the Haitian revolution, religion, anorexia and mania—and utterly exhaustive, since all these parenthetical topics are ultimately also symbolised by sugar and its production. In this kaleidoscope of ever separating and reconnecting topics, full of “objects [that seem] to enter into new relationships, new constellations with each other”, Dorothee Elmiger—or rather, the narrator she pens—is perhaps suggesting that any single thing, if examined both broadly and closely enough, can lead us to everything else (are we singing along with Lauryn Hill that ‘Everything is everything’?); or perhaps she is suggesting that, haunted as the early twenty-first century is by the spectre of colonialism and its aftermath, we are saturated in sugar (some things are more omnipresent than others). Then again, maybe she is implying both or neither of these things, or even that the search for a metanarrative is futile: as Elmiger writes, “I thought I had to somehow gather everything together . . . but now things are imposing themselves on me virtually—I see signs and connections everywhere, as if I had found a theory of everything, which is of course utter nonsense.”

The book tells us it is also about many other things, and amongst this multitude: “A Philadelphia parking lot (NEW WORLD PLAZA) / Desire / Sugar, LOTTO, Overseas”; or later, in a fictionalized account of our fictional narrator, a longer suggestion:

for a while now she has been claiming to friends that she’s been working on a book about love . . . Until now she had stayed away from these things—love, feelings, sex—and this decision had been to her advantage in a certain way: she often received praise for the fact that the spectrum of her so-called “topics” was not limited to what women supposedly usually worked on, but also included the historical-political, or questions about and a vocabulary of technology. Her work was characterized above all by the fact that it bore the hallmarks of a literature that was seen as male.

Are we reading the book about love the narrator refers to? Not quite: While there are love interests dotted throughout, “love” in a traditional romantic sense seems peripheral, and there is neither a tragic moment of heartbreak nor a traditional happy ending (or any real conclusion at all: “If you really think more needs to be told: fine,” we read. “But if you think there’s an end, you’re fooling yourself.”) Instead, “love” seems to be closely associated with research; with storytelling and the (im)possibility of comprehensive communication; with desire, and thus also with hunger—and so we find ourselves again on the topic of sugar.

Perhaps the book’s most persistent narrative motif is the “lotto king” Werner Bruni, Switzerland’s first-ever million-Franc winner, a thoroughly working-class man who after just a few years—and meddling from his wealthy boss—went bankrupt. For the narrator, Bruni is connected with sugar and the history of slavery on a symbolic level as a labourer in a system of industrial exploitation that superficially seems to operate in parallel to, but is in fact inextricably connected with, the plantation economy; and also much more directly through his visit to Haiti. Haiti figures repeatedly in the book: it is the site of Bruni’s holiday and a short story the narrator invents about it; it is the birthplace of the ancestors of one of her lovers; it is explored through a Heinrich von Kleist story and through other European reports of the Haitian revolution and the fate of its generals. For Werner Bruni, Haiti also seems to be symbolic of a paradise lost: “In the book about his life, the life of the country’s first lottery millionaire, it says: ‘Haiti is my most beautiful memory.’ When he thinks of his lost wealth, he thinks of Haiti, and there was not much more left for him”. Initially, Haiti is also believed to be the origin of two travel souvenirs that the narrator sees in a picture of Bruni’s living room.

When looked at more closely, Out of the Sugar Factory’s obsession is perhaps not so much with “WB” (many of the characters’ names are perplexingly initialized) himself, but rather with these “two female figures made of wood or polished black stone . . . unclothed except for some fabric wound loosely around their waists and heads, and gold necklaces”. They seem to have a life of their own— “They kneel in seeming self-absorption”—yet also have ever-shifting, externally imposed significations. Recalling Flaubert, they are, through their later auction, a symbol of WB’s bankruptcy; they are assumed to be a reminder of pleasure, or leisure, or friendship; they become at the auction a symbol of objectified female sexuality— “Just look at those breasts.” The narrator assumes they are connected to Caribbean colonialism, but later realizes they must come from an earlier trip of WB’s, to Kenya and thus a different point in the production line of slavery. For the narrator, they thus become “messengers from the future. Signs. Also: as if they prematurely announced the end.” This misattribution also transforms the figurines into a symbol of our desire to weave disparate elements into something that seems like a cohesive whole.

Out of the Sugar Factory is a text that requires its reader to work to make and maintain connections, while also being hyper conscious of the concept of connectedness. Every page or so, the text shifts between one of its plethora of styles—dialogue; notes; reported letters and telephone calls; dreams; quotation and precis; embedded narratives; and even extracts from a table of contents—forcing the reader to constantly recalibrate, either tuning in to a new topic or picking up a previously dropped thread. It also self-consciously questions the reality of boundaries between fact and fiction: “Why not invent everything, when even the true story is obviously a fiction, or a montage at the very least.” In all its attempts to do so, even the text itself cannot give us a definitive answer as to its genre: the narrator tells us that her editor “says that in case of publication of these notes, ‘novel’ must appear on the cover . . . I say that it is a report about research, which is why “research report” seems incomparably more appropriate to me.” We must remember, though, that Out of the Sugar Factory is close to but is not quite the text that its narrator is trying to write (just as Dorothee Elmiger is biographically similar to but is not quite its narrator), and this is certainly no formally structured report, just as it is not simply a product of research, but also of memory, reflection, and invention. It is, perhaps, a series of attempts—an “experimental configuration of things, this essai”—to get out of the “undergrowth” (which is where the narrator imagines herself at the beginning and end of these pages), or at least to try to enjoy being amidst such dense shrubbery.

And so, on to another attempt to describe this book: You certainly need to enjoy density to appreciate Out of the Sugar Factory. Although the prose is completely unpretentious, it is practically heaving with intertextuality. This begins, in the English version, with the very fact of it being mediated by Megan Ewing’s translation, as Ewing makes her fingerprints clear in sentences that show their debt to the German syntax. This added layer of hypotextuality seems appropriate in a text that already borrows from so many forms and voices, and the occasional linguistic awkwardness of this refreshingly foreignizing translation strategy does not detract from the explorations and innovations in narrative structure, theme and genre, and the ways these can help us explore history, memory, and politics. Ewing makes one aspect of the text easier—she translates quotations, sometimes parenthetically, that in the German original are only in French or English—but otherwise, the wilderness of intertextuality is largely unglossed: In a single page, you might move through references to Marie Luise Kaschnitz (who, the narrator tells us, writes “what has occurred to her in the last few years but ‘not in sequence’”—echoing Out of the Sugar Factory’s own structure), the psychiatrist Ludwig Binswanger, the painter Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, the ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, and then on to Joseph Roth. While some references—such as to Marx, Madame Bovary, Chantal Akerman, or James Joyce—are presumably familiar to the book’s likely audience, others are quite obscure, especially for non-Germanists, and may only crop up fleetingly. This prompts the question of how such a book is to be read: do you let it wash over you in the hope of seeing the woods in spite of the trees; or do you take it as an invitation for hypertextual exploration, moving in a tangent—like the narrator herself—every time something unfamiliar crops up: searching, learning, and thus moving to greater understanding of the whole? The latter seems utopian; the former would squander the effort still required to hold together the strings of this sprawling text.

Despite—or perhaps because of—the work it requires, this book (I keep wanting to write novel, because it certainly feels more like fiction than anything else, despite its grounding in theory and fact; and because it certainly feels literally ‘novel’) has a way of dissolving into and altering your thoughts, much like sugar in coffee. I find myself unable to write linearly, or to describe it except through multiple attempts from different angles; I’ve jotted down disjointed reflections in a notepad, something I haven’t done in years; and I keep returning to passages that now no longer seem “not in sequence”, but rather newly illuminated or rather always-already, if fleetingly, interconnected, “a brief convergence of the most diverse strands of history—as if disparate rocky objects, celestial bodies that had long been circling the sun, seemingly unconnected, suddenly collided, and their impact provided an illumination of things, of rubble and dust, one second long”. Perhaps this feeling is because, much more than conventional writing, the text echoes the way we think and remember, the ways we make connections between disparate objects in order to at least approach understanding.

Rachel Stanyon is a translator from German into English and a senior copyeditor with Asymptote. She holds a master’s in translation and in 2016 won a place in the New Books in German Emerging Translators Programme. Her first full-length non-fiction translation has recently been published with Scribe.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: