Jente Posthuma’s What I’d Rather Not Think About delves into the closeness of a relationship that many find difficult to understand: the inextricable link between twin siblings. Through a delicately woven tale of memory, shared selfhood, and grief, the author takes us into the mind that struggles to understand a world shattered by loss, when one sibling dies and another is left to reconstitute the fragments. Poetic and surprising, Posthuma shows how even in the most intimate of connections, in another person lies the great unknown.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

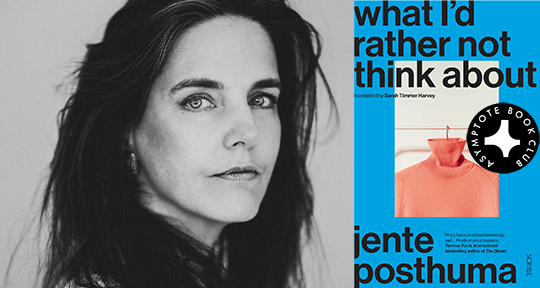

What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma. Translated from the Dutch by Sarah Timmer Harvey, Scribe, 2023

In short, poignant vignettes, What I’d Rather Not Think About is Jente Posthuma’s story of twin siblings: a brother who commits suicide, and a sister who is left behind. True to its title, the novel grapples with the narrator’s dark, complicated feelings of loss following the death of her brother, as she ruminates on the intensity of their relationship. In reflections of the siblings’ childhood and youthful dreams, tracing how these dreams changed or were lost on the way to maturity, Posthuma develops an affecting novel about grief by embracing its full complexity.

From its opening passage, Posthuma hints to the darker turn the twins’ story will take; the first memory shared is of the two experimenting with waterboarding as children, after seeing a film about Guantanamo Bay. To this, their mother sighs, accurately guessing that: “this has to be one of your brother’s ideas”. The untraditional game cleverly introduces their relationship, with the brother being more in control of their makeshift experiment, leaving the narrator coughing and spluttering from the experience. She asks her brother: “Why didn’t you help me?”, and only receives a single “sorry” in return. This pattern of behavior continues as adults, such as when the narrator joins her brother in a diving lesson, since “my brother expected me to follow him because that’s what I always did. If I wanted to go in a different direction, he would ignore me and keep walking.”

Throughout the novel, we see this trend of radicality in the narrator’s brother as he searches for happiness and the meaning of life, often with total and often obsessive interest: pursuing animation with a fascination with Walt Disney and Donald Duck, becoming a diving instructor in Brazil following a break-up, or joining the Bhagwan religious movement. But Posthuma doesn’t shy away from showing the bias in the narrator’s shifting reflections of her brother; the pair are presented as having the same problems of all twins or siblings, with a more dominant, older individual taking lead. It quickly becomes apparent that some resentment continues to exist with the living sibling, adding more depth to the story’s central question: what happens to the definition of a pair when one half disappears?

My brother called himself One and me Two because he had been born forty-five minutes earlier in a sweltering day in August. He treated me like his little sister. . . our actual due date had been a month later but my brother had gone ahead, and I wasn’t about to be left behind.

In the depiction of the siblings’ childhood, their mother often proudly claims: “my son is good at everything. . . One day, he’s going to do something extraordinary.” For every mother, this hope for the future is never out-of-reach, considering the subjective nature of what can be extraordinary. Yet, being blatant about her son’s fate and the maternal dreams left in ruins, Posthuma explores the pathos of her inevitable disappointment as well as the sister’s part in setting up the dynamic of the younger twin’s reliance on her brilliant brother.

There are occasional moments of levity and humour against Posthuma’s minimalist, often devastating lines, and as the narrator’s memories shift back-and-forth in time, one is reminded of her control over the narrative and the power of hindsight in seeing certain links and associations—that which we all try to make in order to find meaning, amidst the threats life makes to our sense of order. By initially keeping the details of her brother’s suicide brief, the novel moves forward in the narrator’s moving, investigative hunt to find the key moment of change in their relationship, rather than gathering momentum towards the tragic event. In reaching backwards, she lingers upon the significances of relationships, of jobs, and most importantly, of cities—which take on a resounding symbolism within the book. Despite travelling and then living abroad in Amsterdam, the two promise one another to move to New York together at twenty-eight, the year their father “believed people truly become adults.”

When tensions emerge between the two at the birthday party celebrating this milestone, the call of New York is accentuated with the Twin Towers reoccurring in the narrator’s reflections—from her early dreams of seeing the towers up close, the image of it hanging above her childhood bed, to the siblings’ reaction to 9/11. Indeed, in Posthuma’s deliberately short vignettes, we often find the narrator’s most truthful and revealing reflections as she tries to find examples of role-reversal in other twinships: when the leader learns to listen and submit to the other.

The North Tower was called 1 WTC, so the South Tower was called 2 WTC. 1 WTC was 417 metres high and 2 WTC was two metres shorter. 1 WTC had an antenna on the roof and was completed in 1972, a year earlier than 2 WTC, which did not have an antenna. For a short while, 1 WTC was the tallest building in the world, until Chicago’s 442-metre-high Sears Tower surpassed it in 1973. This was a bitter pill for 1 WTC to swallow but what is worse? To have briefly been the tallest building in the world or to have never been the tallest building in the world because the building next to you was always slightly taller.

In another moving thread, the depth of the narrator’s grief can be glimpsed in her thoughts about the seemingly innocuous love her and her brother shared of the castaway reality competition, Survivor. Watching the show, the narrator notes that the best contestants aren’t the strongest but simply the most frightened—the ones endlessly seeking protection from others. She concludes:

My brother’s life was a series of poor Survivor decisions but the stupidest thing he did was break his alliance with the only other contestant he could trust, the one who would have given him her last grains of rice, who would have carried him on her back to the finish line if it came to that.

Rather than emitting a desire to align herself with traditional visions of heroism, the narrator seems to find more comfort in resigning herself to this supportive role, ultimately finding a different strength. Our narrator will never get her heroic moment of saving her brother, but with this final act of service, of remembrance, she has set out to prove her devotion towards her brother’s survival—if only there was still a chance.

Daljinder Johal is an assistant managing editor at Asymptote. She works as a producer, curator, marketer and writer in film, theatre and audio to create joyful and thoughtful work that shares nuanced perspectives from voices often underrepresented in the arts and film industry. She has a particular passion for highlighting the creativity of regions outside of London.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: