This edition of Principle of Decision—our column that highlights the decision-making processes of translators by asking several contributors to offer their own versions of the same passage—provides a look at how translators render the subtleties of a poem with multiple layers of meaning in a new language.

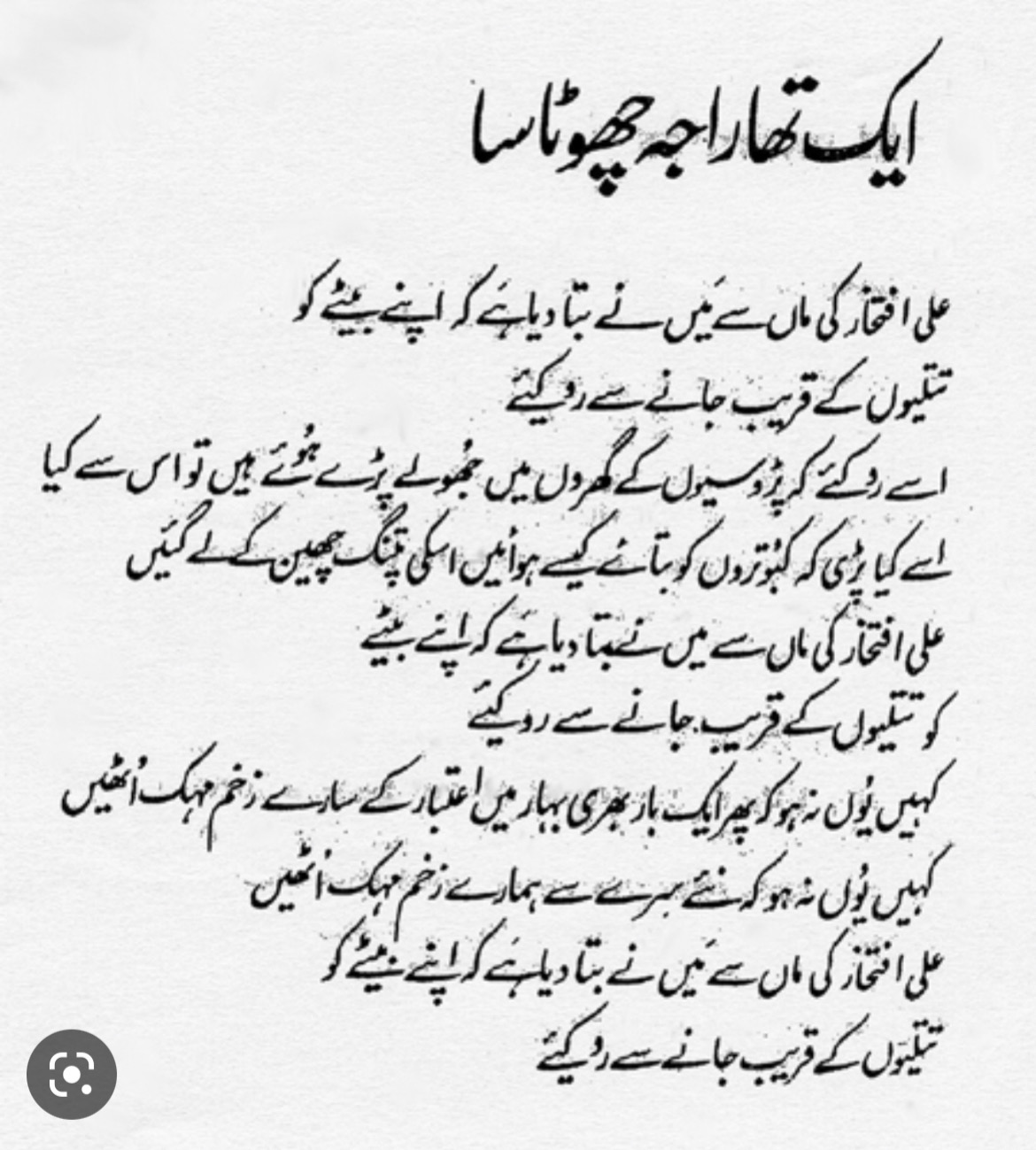

I chose a poem by Iftikhar Arif, a revered Urdu poet. It was written for his son, Ali, and was published in his first volume of poetry, Mehr-e-Doneem (The Divided Sun, Daniyal Publications, 1983). This poem is a father’s sendoff; as he says a farewell to his son, he feels a lump in his throat and slips some blessings and lessons for the future into his farewell, barely masking his fear. A companion piece, the short poem “Dua” (Prayer), was written for his daughter, and published in the same volume, containing a similar wish of goodwill.

The poem is not to be read at face value. Defeat is baked into its premise, and what the poet is saying out loud, he knows to be the opposite of the truth. It is a prayer for the impossible, asking a grown man not to lose his innocence. There is rupture in the title itself: Aik tha raja chota sa—(once upon a time) there was a little prince. It’s the tone in which you speak to a child, who is uninitiated into the realities of life. It’s the tone of lullabies. There is a clinging to a make-believe world in the language, an attempt to soften the edges, to make the truth less harsh, to almost wish it away.

The first word of the first line starts with the son’s full name, Ali Iftikhar. The once-little prince is a grown man, which the poet acknowledges, but then slips back to addressing the grown man through his mother, a line repeated thrice in the poem: “I have told Ali Iftikhar’s mother not to let him…”.

Throughout the short poem, there is a push and pull. On one hand, there’s an attempt to glaze over the truth and to control the circumstances; on the other hand, there’s truth leaking through the veneer of denial. The repetition is like a broken record to convince the speaker himself. There is also a contrast between the naïveté of the language and the knowledge of truth beneath it—and bridging both, a father’s love. He tells the son to stay away from the corruption of the world by asking his mother to keep him from transgressing the different circles of protection: the garden, the neighbour’s garden, the street and the world beyond. Which grown man hasn’t transgressed these limits?

The four translators, sensitive to the central challenge posed by the poem, have found different solutions to address the tug in the original. Farah Ali is alert to the rhythm and pace in the original. Hammad Rind pays attention to calibrating the register and forms of address, important tonal considerations for the poem. Haider Shahbaz brings an experimental take to his reading, leaning into its dark undertones. Sabyn Javeri sees the poem through a feminist lens, asking questions that trouble her as a woman.

I’ve always seen translation as a conversation—a conversation between the author and the translator, the translator and the work, a translator and other translators, a translator and a reader. This folio shows how rich that conversation can be. Each of the four translators interacts with the same, short poem through the filter of their individual personalities.

—Naima Rashid

Farah Ali

There was once a little prince

I have asked the mother of Ali Iftikhar to tell her son

not to get close to butterflies,

to stop him—what should it matter to him that there are swings in the neighbors’ houses;

what should it matter to him to tell the pigeons how the winds snatched his kite from him?

I have asked the mother of Ali Iftikhar to tell her son

not to get close to butterflies.

What if, in only one blossoming spring, all the wounds of trust fill the air with their perfume.

What if, once again, our wounds fill the air with their perfume.

I have asked the mother of Ali Iftikhar to tell her son

not to get close to butterflies.

Arif wrote this poem for his son, Ali Iftikhar. The things he is asking—that the boy stay away from fleeting sources of joy—are a father’s attempt to protect his child, albeit grown, from hurt. The request is almost unreasonable but contained within polite, formal Urdu, from the manner of addressing his son—indirectly through the mother—to the choice of words— اپنے بیٹے کو, the formal word for “her”, and روکئے, the formal verb for “make him/her stop”. For these lines, doing a literal translation came the closest to conveying the original tone.

The formalness is the poet’s attempt to continue exerting protective control over his child, but the parental tone falters soon after. To emphasize that breakdown, I added punctuation to aid the work of the English words. In particular, I added the em dash in the third line to zoom in on the two instances of possible unhappiness that Arif describes. The lines that show the most vulnerability come almost toward the end. In Urdu, Arif places the words for wound, perfume, and diffuse next to each other, six rhythmic syllables. To give that same sense in English of the dispersal of pain, I prolonged the description of that act, to draw it out till the end of the line.

Hammad Rind

There Once was a Little Prince

To Ali Iftikhar’s mother I said,

Stop your son from chasing butterflies

Stop him, for if there are swings in the neighbours’ homes,

Why should he care?

Why should he tell pigeons how winds snatched away his kite?”

To Ali Iftikhar’s mother I said,

“Stop your son from chasing butterflies,

In case the wounds of trust bloom again,

When the spring is in full swing,

In case our wounds bloom again”

To Ali Iftikhar’s mother I said,

“Stop your son from chasing butterflies”

At the centre of the poem is the verb “stop” being repeated a few times in the polite imperative form, “rokiye”. While the use of the politer form (rather than the more ‘neutral’ “roko”) softens the bluntness of the command, it may also give the poem an overly polite or formal tone. Although one might be tempted to translate it similarly, it is important to consider the writer’s Awadhi background and understand that this is a common way of addressing one’s spouse in families of this culture. The poem’s neutral tone is moreover clear from the text that follows the imperative. As English only has one imperative form, I chose not to use “please” in order to avoid introducing formality not intended by the poet. The title of the poem features the word “raja” in Urdu, which may be familiar to English speakers due to its association with the figurehead rulers of princely states in Raj-era India. However, I made the choice to avoid these associations by opting to translate the word as “prince”, so that the intended meaning of the text was not overshadowed by the historical baggage associated with the original term.

Sabyn Javeri

Once There Was a Little Prince

I have told Ali Iftikhar’s mother to stop her son from chasing butterflies

To warn him that the swings in the neighbour’s garden are not for his pleasure

Why, then, must he narrate the adventures of his kite being snatched by the winds to the pigeonsI have told Ali Iftikhar’s mother to stop him from chasing butterflies

Lest once again in the throes of spring, the wounds of betrayal become septic

Lest, once again these wounds split open, their odour pungent and raw

I have warned Ali Iftikhar’s mother to stop him from chasing butterflies

Urdu is a language rich with subtext, where the tone of a word often conveys more than its meaning. Keeping the tone of the word ‘told/ بتا دیا’ alive in this poem was challenging because it was difficult to capture the context of the original without altering the vocabulary. While the word “told” itself does not change in the original as the narration progresses, its tone does. As the poet tells his son’s mother to control his (mis)behaviour, the tone progresses from a gentle reminder to a dire warning. Therefore, I made the choice to express the different attitudes the word was conveying by altering the words in English. In the first line, he “tells” the mother, but towards the end the tone changes, as he “warns” the mother. In between, he depicts a series of consequences that may follow if the son’s behaviour goes unchecked.

Another stylistic choice I made was to translate the imagery through context rather than through a literal translation. For example, though the imagery used in line two: “. . .that the swings in the neighbour’s garden are not for his pleasure,” convey a concern about intrusion into the neighbour’s garden, the undertone is that of curbing frivolousness or perhaps flirtation. Similarly, butterflies are often associated with femininity and vulnerability in Urdu Adab, and spring with youth. Due to this, I changed the literal translation of “stop him from getting close to the butterflies” to “chasing butterflies” as it conveyed the meaning of the son’s carefree behaviour and desire more aptly, butterflies alluding, perhaps, to vulnerable and impressionable young women in the neighbour’s garden.

On a personal note, the most challenging aspect of this translation was the patriarchal overtones evident in the shifting of responsibility for a son’s behavior solely onto the mother. I couldn’t help but question, why can’t the poet tell his son himself? In a society where women have very little social influence, whether in the public space or private sphere, what authority would Ali Iftikhar’s mother have over a son who had more freedom than she did to wander outside, due to his male privilege? Capturing these societal expectations in the translation was perhaps the most frustrating as well as the most rewarding part of the process.

Haider Shahbaz

There was a Prince, a little Prince…

I warned the mother

of Ali Iftikhar: do not

send your son near larvae.Tell him: what is it to him

If there are abandoned empty

Swings in the neighbour’s house.

What is it to him. Do not discuss

With the pigeons how the wind

Stole your kites.I warned the mother

of Ali Iftikhar: do not

send your son near larvae.What if, once more,

The lesions of our trust

Bloom in full spring.

What if, once more, the scent

Of lesions in spring.I warned the mother

of Ali Iftikhar: do not

send your son near larvae.

I have always gravitated towards the idea of translation as treason. The translation as a betrayal, as a lack. These are words that are often used to tell translators that their work is secondary, or a second-order text. But I love secondary things and ideas because they carry the promise of a change. They tell us that things can be revised, reworked, retold, remade. The word—and world—can be different. I find this hopeful. I do not like the idea of things being original, timeless, or primary. These are Platonic ideas, and to put it simply—Plato was wrong.

Instead, I like the potential of translation to make something new and modern. And so, I’ve tried to translate this poem by one of the greats of Urdu poetry by betraying it. The Urdu poem is romantic and familial. I have attempted to hear the dark, forbidding uneasiness that lies underneath it, reverberates through it. Romance can be very close to the gothic and to horror. I hope you can hear this proximity in the translation.

Naima Rashid is an author, poet and literary translator between Urdu, English, French and Punjabi. Her work was longlisted for National Poetry Competition and Best Small Fictions. Her published and forthcoming books include Sum of Worlds (Yoda Press, 2023-2024), Naulakhi Kothi (Penguin Random House India 2023), Chicanes (Les Fugitives, 2023) and Defiance of the Rose (Oxford University Press, 2019). Her writings have been widely published in journals of repute, including Asymptote, The Scores, Wild Court, Poetry Birmingham, RIC Journal and Litro, among others. She is a collaborator with the UK-based translation collective, Shadow Heroes, which teaches young people to embrace all aspects of their linguistic and cultural heritage.

Farah Ali is from Pakistan. She is the writer of the short-story collection People Want to Live. Her work has been anthologized in Best Small Fictions and the Pushcart Prize where it has also received special mention. Her stories have appeared in Shenandoah, Kenyon Review, Ecotone, and elsewhere. Her translation into English of Ghulam Abbas’s Urdu short story, “Overcoat”, is forthcoming from Pleiades. Her novel, The River, The Town, is out in Autumn 2023. She is currently slowly translating Ghulam Abbas’s collection of short stories in his book “Jade ki Chandni” (Winter’s Moonlight).

Hammad Rind is a British-Pakistani writer and translator. His debut novel Four Dervishes (Seren Books, 2021) was longlisted for the British Science Fiction Award in 2022. His Urdu translation Uljha Gham of Naveen Kishore’s debut poetry collection Knotted Grief was published in 2022 by Zuka Books. Hammad did a BA in English and Persian Literature and an LLB at the University of the Punjab, and an MA in Filmmaking at the Kingston University, London. His stories and articles have appeared in a number of UK and international magazines.

Sabyn Javeri is the author of ‘Hijabistan’ (Harper Collins: 2019) and the novel ‘Nobody Killed Her’ (Harper Collins: 2017) and has edited two multilingual anthologies of student writing titled, ‘The Arzu Anthology of Student Voices’ (Vol I & II. HUP: 2019, 2018) and the recently published, ‘Ways of Being’ an anthology of Pakistani Women’s Creative Non-fiction (Women Unlimited, Jan 2023). Her writing has been widely anthologized and published in the Oxonian Review, South Asian Review, London Magazine, Litro, Bookends Review, Journal of Commonwealth Literature, Wasafiri, Trespass, amongst other publications.

Haider Shahbaz is a writer and translator from Pakistan. He is the translator of Mirza Athar Baig’s Hassan’s State of Affairs (HarperCollins) and the editor of a special volume, “Against the Canon: Urdu Feminist Writing,” for Words Without Borders. Other writings and translations have appeared in Fence, Asymptote, Brooklyn Rail, Los Angeles Review of Books, The Caravan, Dawn, and elsewhere. He is currently doing a PhD in Comparative Literature at UCLA.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: