A story about the dissolving borders between human and animal, life and death, love and cruelty, Venom by Saneh Sangsuk is a kind of philosophical fairy tale, with both danger and beauty always lurking at its edges. Told through shifting perspectives in poetic prose, this slim novel is densly packed with ideas and energy, providing a thrilling introduction to Sangsuk’s work for English-language readers.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

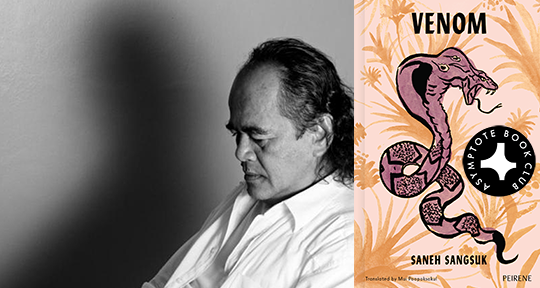

Venom by Saneh Sangsuk, translated from the Thai by Mui Poopoksakul, Peirene Press, 2023

The world is full of poetry; the world is full of cruelty—this is not a contradiction. As I read Saneh Sangsuk’s deceptively slim novel Venom, I was reminded of Laura Gilpin’s “Two-Headed Calf.” At barely nine lines, Gilpin’s poem also has depth that reaches far beyond its brevity. The first stanza begins with a warning (that the idyllic pastoral will soon be disrupted), while the final stanza establishes a heart-wrenching and melancholic portrait of a recently-born, two-headed calf revelling in the light of the moon, “the wind on the grass,” and the warmth of its mother. The beauty of Gilpin’s poem lies in the way it holds two worlds in its lines, but also in how it makes possible for a cruel tomorrow to never arrive. In a sense, by returning to this poem, we are returning to a moment in another world where a two-headed calf—this “freak of nature”—is frozen in an eternal evening of joy and love.

I found in Venom the same sensations, the same negotiation between poetic beauty and cruelty. The former comes quickly and easily, as the book opens with a little boy contemplating a mesmerizing sunset in the Thai countryside: “Over the horizon to the west, the clouds of summer, met from behind by sunlight, glowed strange and lustrous and beautiful.” Additionally, the first thing we learn about this boy is that he was granted the privilege of naming his family’s eight oxen, and he had been eager to fulfil this task with care and artistic flare. He calls the animals by names like “Field, Bank, Jungle and Mountain—Toong, Tah, Pah and Khao,” and “Ngeun and Tong, Silver and Gold,” or “Pet, Ploy, Ngeun and Tong.” These group of names speak to him with prosodic logic: some rhyme, and others provide a chance for alliteration. All in all, they belong to a group of words that “sounded like [they] could be poetry,” a phrase that Sangsuk repeats twice. This act of naming, the author suggests, is an act of writerly creation. While the world is not inherently poetic, some people are more prone to make poetry from its elements.

Yes, the unnamed protagonist of Venom is, at heart, a poet. He looks at the sun and the sky and it sparks his imagination. After the oxen are done for the day, sometimes he creates rudimentary puppets, putting on shows for his friends. These performances are also accompanied by recitations of fragmented odes and epics, which enthrall his audience: “He could see in his friends’ eyes their hunger for entertainment; children are always seduced by silly rhymes.” The frivolity of “silly rhymes,” however, belies an earnest nature, as elsewhere we learn that he “took playing very seriously—no matter the game, he always put his heart and soul into it.” In fact, the act of playing, of creating stories through words, sticks, and light, provides for the boy a path to the future, as he dreams of the day when he will entertain much bigger audiences as a shadow puppeteer.

And yet, the little boy receives little in return for the poetry that he gifts the world. For every moment of beauty, there is the shadow of cruelty hanging in the background, alluded to in the very title of the book and clashing with the bucolic introduction. Though we do never, in fact, find out the protagonist’s name, he is given a vicious moniker; in the world of the novel, he is called Gimp, “because his right arm, from the shoulder down, was atrophied and hung stiffly by his side”—the result of falling from a tree. One particular person takes a twisted kind of joy in calling him Gimp; a local medium called Song Waad loves to say it “with disdain and hatred, relishing the opportunity to remind himself and other people in the village of the boy’s imperfection.” Song Waad is the boy’s foil—a local farmer who had refashioned himself as a medium of the Patron Goddess of Praeknamdang, sidestepping other spiritual individuals in the community and making himself a revered figure though sheer willpower alone: another clear indication of the power of naming that runs through Venom.

But Song Waad represents much more than a simplistic antagonist. As Mui Poopoksakul writes in her translator’s note, Venom is a love letter to Sangsuk’s birthplace, represented by the fictionalized village of Praeknamdang, where the author’s other works take place as well. But unlike his contemporaries in the literary movement of Thai social realism (which Poopoksakul explains is also referred to as “art for the sake of life”), Sangsuk refuses to idealize Thailand or the countryside of his youth. While his writing is marked by a poetic melancholia that imbues the narrative with nostalgia, Praeknamdang is not an uncomplicated home. Sangsuk appears to condemn the credulity of local inhabitants who are quick to submit to Song Waad and take his word as gospel, and who even bully the protagonist of Venom following his lead. Meanwhile, under the guise of his position as medium, Song Waad has appropriated a local pond where the boys used to play and villagers fish. What was once communal, then, becomes the private property of the Goddess—namely of Song Waad, as her medium.

Yet, Sangsuk’s own aesthetic commitments, outlined again by Poopoksakul, mean that we can’t only map a straightforward reading wherein Song Waad stands in for destructive, capitalistic greed—though of course such a reading wouldn’t necessarily be wrong. Instead, Sangsuk “does not believe literature can bring about social change.” As much as he is wont to depict such issues. Poopoksakul specifies that for “Sangsuk, writing is, instead, a personal act. . . he always has an intended reader in mind, an intended addressee.” Because it refuses to subsume itself to a clear moral or even political matrix, the vast majority of Venom is not interested in leading us to a simple showdown between the young boy and Song Waad, as might be expected from the introduction. Instead, the book becomes about a formidable fight between the boy and a king cobra that tries to strangle him.

In a fairy tale-like sequence that takes up the better part of the story, the boy and the snake wrestle for dominance, and we learn that the men in the boy’s family have a long history of encounters with such creatures. As the boy runs around the village looking for help, the two creatures become a monstrous whole, further amplifying the boy’s strangeness to the villagers (in addition to the alienation imposed on him because of his arm). Interestingly, the snake is not an enemy akin to Song Waad; rather, Sangsuk dedicates a portion of the book to the creature’s perspective, lending it empathy as we are given an understanding of its twisted and carnal motives for wanting to kill the boy—though we might wish otherwise.

For a book of barely eighty pages, the narratives and poetic strands of Venom run deep. In addition to being a writer, Saneh Sangsuk is also a prolific translator of Western classics, including Hemingway, Kafka, and García Márquez. In Venom, we find echoes of his intellectual and literary lineage. In one moment, as the boy is struggling with the snake and thinks he might die, Sangsuk writes: “Even on that threshold between life and death, he could still call up the names of all his oxen, and he was overcome with sorrow and longing.” This particular line harkens to the scene of Prince Andrei’s death in Tolstoy’s War and Peace (translated by Constance Garnett). At his deathbed, the prince is overwhelmed by how much he loves this earth: “‘Can this be death?’ Prince Andrei wondered, with an utterly new, wistful feeling, looking at the grass, at the wormwood and at the thread of smoke coiling from the rotating top. ‘I can’t die, I don’t want to die, I love life, I love this grass and earth and air . . .’”.

In another episode, as the boy contemplates the cruelty with which he is treated by the villagers, he thinks about his own stance towards love: “He had tried to make himself love others as well, but he realized that he still loved the people who were good to him more than he loved the rest of them.” Something about this deep contemplation by a young boy of how he should respond to the world reminded me of Dostoevsky’s Alyosha, a key figure in his Brothers Karamazov and the notion (and burden) of active love. Active love refers to the desire to love and save humanity, a feeling that operates alongside the deep knowledge that individual people may hate you without reason, and you cannot make yourself love them back despite your own good intentions.

I am not sure that these references are conscious, but these poetic symmetries—like the broader nostalgic and melancholic feeling of the novel—are owed to Poopoksakul’s translation. Poopoksakul is a key figure of contemporary world literature; through her translation and editorial work, she has been instrumental to the publication of Thai works over the last half decade, from Prabda Yoon’s The Sad Part Was and Moving Parts, to Duanwad Pimwana’s Arid Dreams. Throughout this varied body of work, her translation has proved to be truly chameleonic: if there are some translators that subsume every writer to their own personal style, Poopoksakul is instead capable of shapeshifting with each author while maintaining a highly original voice. It is through her words that Sangsuk’s world comes to us, a poetic fairy tale brimming with both tenderness and danger. She has rendered Sangsuk’s sentences in a melodic style that retain the childlike wonder of its protagonists’ point of view, without ever sacrificing its philosophical complexities. If Sangsuk has managed to preserve a vision of a bygone era and place through his fiction, Poopoksakul’s English translation has given it another language, another home to keep that flash of memory alive in the mind of other readers.

Barbara Halla is a PhD student in Romance Studies at Duke where she works on contemporary French and Italian literature, feminist theory, and literary criticism. She also serves as Asymptote’s Criticism Editor. Barbara’s reviews have appeared in Asymptote, Reading in Translation, and Europe Now, among others. Her essay on Annie Ernaux and the politics of female desire was published in the anthology Le Désir au Féminin (Ramsay Editions, 2022), while her article on the canonization of Albanian women writers in the fiction of Musine Kokalari is set to appear in the academic journal Balkanologie in Fall 2023.

Our website is supported by our users. We stand to earn a commission when you click through the affiliate links on our website.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog:

- Announcing Our May Book Club Selection: Mister N by Najwa Barakat

- Announcing Our April Book Club Selection: The Spectres of Algeria by Hwang Yeo Jung

- Announcing Our March Book Club Selection: Siblings by Brigitte Reimann