Amidst the mysterious, intricate narrative of The Specters of Algeria, there is another elusive, shrouded text: the only play that Karl Marx had ever written. This absurdist work, which gives the novel its name, goes on to inflict immense violence onto a circle of close friends, initiated by the hotheaded crackdowns of a censorious regime. In her generation-spanning, multi-threaded debut, Hwan Yeo Jung spins a fascinating inquest into authorship, aesthetics, authoritarianism, and how such things resonate into our intimate relationships. As the arrival of an exciting new voice in Korean writing, we are thrilled to introduce this fascinating inquest into political and human nature as our Book Club selection of April.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

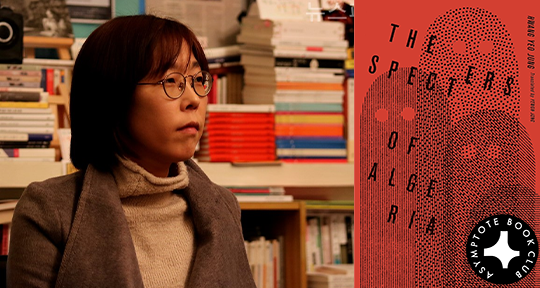

The Specters of Algeria by Hwang Yeo Jung, tr. from the Korean by Yewon Jung, Honford Star, 2023

In her theorizing of anti-neocolonial translation, Don Mee Choi has described the experience of speaking as a twin—in the context of a Korea divided by colonial powers in twain, existing inside a language that has been colonized and recolonized by invasion and annexation, Choi describes the act of translation from between two nations that have never technically stopped being at war. This twinning across history is an idea that came to me again and again as I read The Specters of Algeria by Hwang Yeo Jung, translated by Yewon Jung. Hwang Yeo Jung’s first novel, released in Korean in 2017, takes an incredibly cerebral dive into the minds of two childhood friends who do not quite understand the circumstances of their own upbringing. In seeking answers to the dissolutions of their families and friendships, Yul and Jing (who are also Eunjo and Hyeonga, and maybe also Yeonghee and Cheosul, and maybe also Lily and Marx) sink deep into the fog of memory and a historical era, whose sins are often swept under the rug.

This labyrinthine novel bears rereading, as moments that were baffling on first readthrough settle into clarity when revisited. In the first chapter, for instance, we learn that Yul’s father, Han Jiseop, is terrified of books and paper, burning every scrap he discovers in Yul’s secret keepsake box of Jing’s letters. As a child, Yul does not understand her father’s fear. It is only later in life that Yul learns her father was once a playwright who, along with the rest of his theatre troop (including Jing’s parents), was arrested for producing “seditious materials” about communism. The resulting violence against Jiseop and his fellows ripped their friendships, and in some cases even their minds, apart. When Yul comes upon Jing’s mother Baek Soi on Jeju Island, Soi’s mind has crumbled completely, able to remember only her son and nothing else. But inside her backpack is the titular play that caused them all so much anguish—The Specters of Algeria.

This play resurfaces in Soi’s broken mind, haunting her with memories of times before the break, and pointing to one of the key concepts of this novel—the importance of naming. In her mind’s eye, Soi travels back to recitations at gatherings when Yul was a child:

“What on earth does it mean for someone to feel something about something?” Jing’s mom asked.

“Do you want to be human?” my dad asked in return.

“Tell me a secret,” she said.

“A secret about what?”

“About anything.”

“Find a contradiction.”

“If I do, will you give me a name?”

“Why do you need a name?”

“Because I need courage.”

“Then I will.”

“What is my name?”

“Hammonia.”

“And who are you?”

“Who am I?”

“Fred.”

As you might guess from all the non sequiturs in the dramaturgical dialogue, the fictional The Specters of Algeria is an absurdist play which points to the larger problem of governments’ absurdist stance towards truth and fiction. The play was viewed as dangerous by South Korea’s authoritarian government not because it was truly anti-government or pro-communist, but rather because it was purportedly written by Karl Marx. The story goes that Marx wrote the play while he was staying in Algeria to convalesce. He asked a maid, Lily, to post it to his daughter, but Lily couldn’t resist snooping in the unsealed envelope. There she discovered the play, and though she could not speak or read German, she was determined to read this work. She made a longhand copy of the play before posting the original, and many years later it was she who had the play published. This strange series of events already draws up questions about original and copy, first and second twin. Can a copy by a woman—who, at the time, did not speak the language—be trusted, especially when she herself went on to be a writer? Can that copy, translated first to French and then to Korean, smuggled across borders and disguised to avoid customs agents, then be further trusted when disseminated to the theatre group?

However, as it turns out, none of these are the right questions, because the origins of The Specters of Algeria are more complex still. The play was smuggled in by a North Korean spy named Pak Seonwu, who obtained it not because he was interested in the art of the theatre or Marx’s only play, but rather by happenstance while spying for the North. But this too is a lie. In truth, the play was written by Jiseong, Soi, and their spouses. The story about Marx was hatched by Jiseong and Tak Osu, the man who cared for Yul and Jing while their parents were under arrest. It was supposed to be a joke, a hoax to play on the rest of the theatre company. Or, maybe this too is a lie. As Tak Osu tells the aspiring dramaturge Cheosul, the truth is not so simple:

[Osu asked,] “What do you think?”

Kim Cheolsu fell silent.

“Nothing you say will turn the truth into a lie, or vice versa. So just relax and spit it out.”

“I … I don’t know. I don’t think it’s something I can judge.”

“Every story is a mixture of truth and lies. Even when people see and hear the same thing at the same time, they each recollect it differently. Sometimes, even what you hear and see and experience for yourself isn’t true. You either experience it without realizing that it isn’t true, or you just don’t remember it correctly. Sometimes a lie turns into the truth, when someone believes it to be true. They could have been deceived, or they could have just believed it; they could have let themselves be deceived, or they could have wanted to be deceived. …”

The style of The Specters of Algeria is one that has become prominent among many young Korean writers; even as the book tackles deep existential questions, the words float on the surface, barely dipping down into deeper waters. Characters do not expose themselves and their inner workings, instead letting thought flow into thought ceaselessly, in a manner that is not quite stream of consciousness but is also not quite not stream of consciousness. Translating that juxtaposition of complex questioning and spare description is no easy feat. The temptation to flesh out or alter the text into something that veers towards aesthetics rather than ideas remains an Orientalizing danger. Yewon Jung’s translation, and its refusal to adorn the prose’s style or clarify, twins the Korean and resists the colonizing impulses of the globalized literary market. Yet, at the same time, she is still attentive to the globalized styles that linger within the text, particularly in the excerpts from the script—the supposed translation of a translation of a translation inflected by yet another translation, that of Antigone .

After all, what matters within this work is not art or aesthetics, but rather how ideas are interpreted. In jail, the writers try to explain to the authorities that the play is a hoax, a joke they wrote to play on their friends. But their joke was too skillful, because their friends believed it to be true. And even if the police had believed the writers, it wouldn’t matter. As Osu says, “What was true or not didn’t matter to [the police]. Or I should say, the facts were predetermined. It wouldn’t have made an ounce of difference if The Specters of Algeria had never existed in the first place.” The state holds its own truths, just as we each individually hold our own truths. Fact and fiction are irrelevant. And when our facts and fictions are disrupted, we are left rudderless, drifting beyond the borders.

The reviewer would like to thank Professor Ji-eun Lee for providing textual insight and historical context.

Laurel Taylor is a translator and Ph.D. candidate in Japanese and comparative literature at Washington University in St. Louis. Her writing and translations have appeared or are forthcoming in Monkey, the Asia Literary Review, Mentor & Muse, and more.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: