Over the weekend, Iran’s Deputy Attorney General said that punishment for those who encourage others to remove their hijabs would face criminal prosecution, and only days before, it was reported that women who were not wearing the hijab were being barred from the Tehran metro, leaving many unable to go to work. This comes at a time when tensions surrounding the longstanding and long-protested compulsory hijab law are especially high; last year, after Mahsa Amini was killed in police custody following her arrest for allegedly failing to comply with the compulsory hijab law, protests against Amini’s killing and against the compulsory hijab law broke out and grew into a larger protest movement. While the protests were violently repressed by the government, the spirit of protest in Iran has both a longer history and a continuing energy. Many Iranian women continue to go without the hijab in public as a display of defiance, and even prior to the recent protests, resistance to the compulsory hijab law was inextricably linked to older Iranian protest movements. The visual histories of these interconnected protest movements are on display in the work of Some Artists, an anonymous group of artists who began using social media to disseminate art in solidarity with Iranian protesters following protests in 2018. In this edition of our series spotlighting visual content from our archives, we revisit our feature on Some Artists from our Winter 2020 issue.

Following the protests of January 2018 and the ensuing silence of the middle class, artists and intellectuals in the face of protests by workers and the rise of the afflicted, we aimed to become a bridge. A visual cry for the afflicted and a platform where artists and intellectuals would be translated beyond class.

The first piece uploaded on Some Artists’ Facebook page was a video clip dedicated to Sina Ghanbari, entitled “(Far)yad” [“Cry 1”], on January 27, 2018.

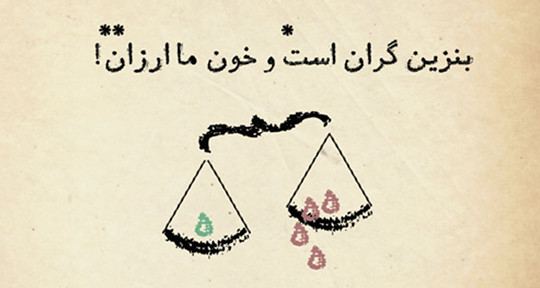

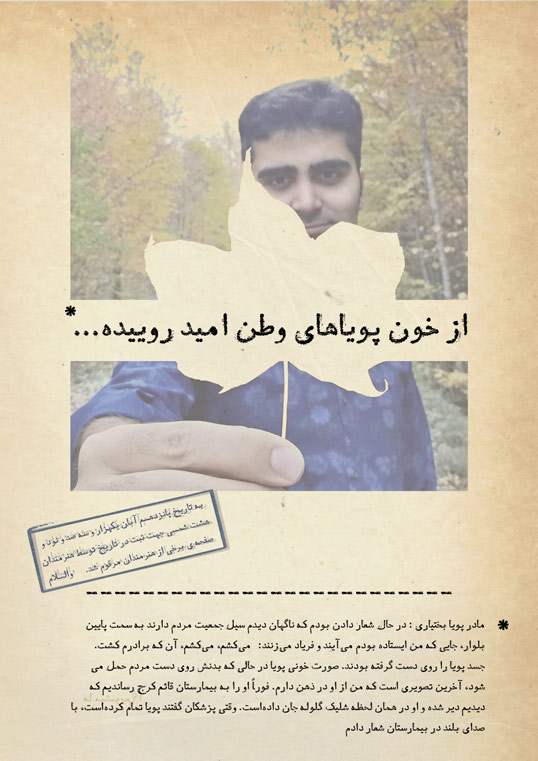

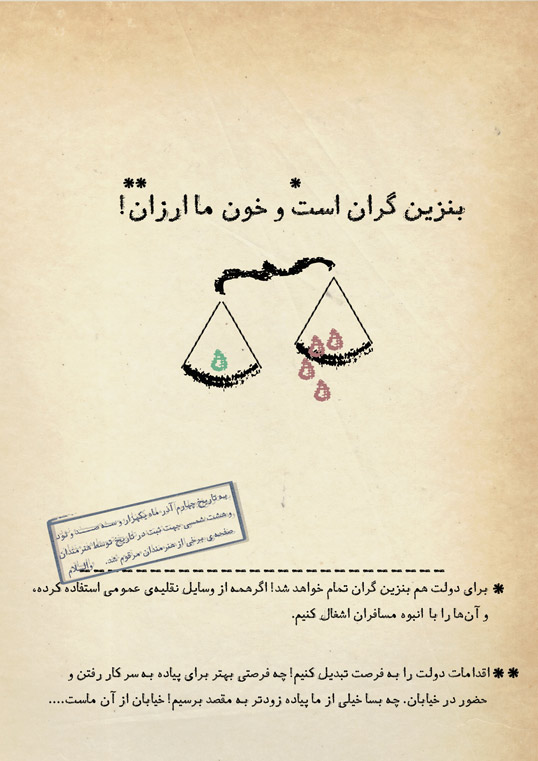

We realized a lack of precedence of visual language for what we hoped to do, and this made our process hard. Whatever existed before then was either the literature and visual arts belonging to the era of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, which felt aged, or the politicized visual language of the Green Movement of 2009; there was nothing else. To address the issue, we decided that a simplicity in form and content would be our only way to go.

New forms of resistance were forming, forms that were their own kind of artwork and performance. We were witnessing creativity in people’s spontaneous slogans and forms of protest: headscarves mounted on wood sticks held by those protesting compulsory hijab standing on top of electrical power boxes, columns, and walls of the city, on the one hand; and tablecloths covered by workers with tree leaves symbolizing a protest against labor problems such as unpaid wages, on the other hand. The slogan “Death to Laborers, Viva the Tyrant,” on the one hand, and workers dancing and saying jokes in factories, on the other hand. . . .

It was at this point that political songs from the 1979 Revolution were sung in the subway by women protesting compulsory hijab, and not for the cause of a particular political party. It was at this point that we realized we were still continuing on the path of the revolution we had started several generations ago. And we, consequently, realized that the visual language of our page should also, in a way, be a continuation of that very path. Researching books and posters from that era, we were drawn to the layout and font of the so-called “white cover” or samizdat books, which had their peculiar visual identity. We extracted that identity and set out to use it as the main mode for the pieces we were producing for the page.

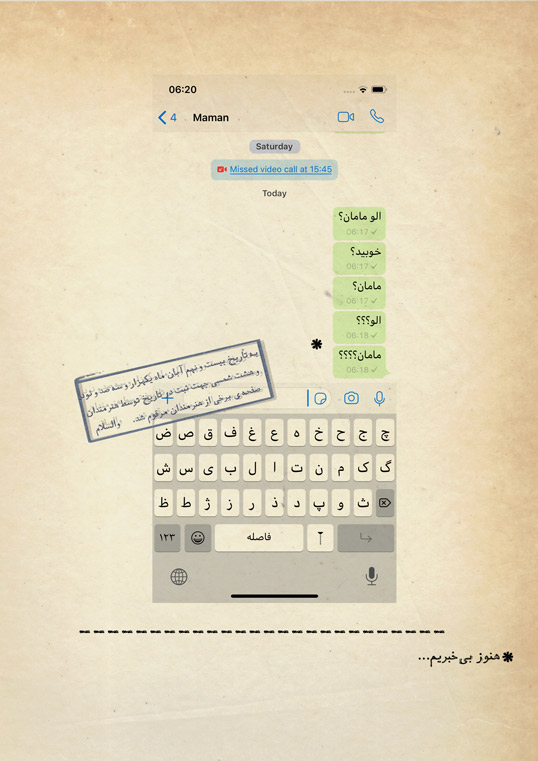

Hello, Mom?

Are you ok?

Mom?

Hello?

Mom????

Images courtesy of Some Artists.

Revisit our feature on Some Artists and the accompanying portfolio of work here.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: