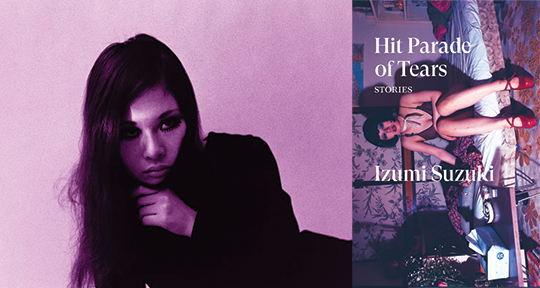

Hit Parade of Tears by Izumi Suzuki, translated from the Japanese by Sam Bett, David Boyd, Daniel Joseph, and Helen O’Horan, Verso, 2023

In the moody, deliriously humorous worlds of Hit Parade of Tears, Izumi Suzuki’s protagonists embody searing emotions, from anguish to apathy, all felt at an apex that seems like a breaking point. Sharp and achingly present, these eleven short stories are transposed by writers Sam Bett, David Boyd, Daniel Joseph, and Helen O’Horan, and present emotional and often unsettling glimpses into worlds both familiar and fantastical. Though each story stands on its own, there are elements that draw them together: the stream of Japanese rock from the 1960s and 70s playing in the background, a woman searching for her younger brother, a blurry line between mental illness and otherworldly abilities, and perhaps most consistently, a spotlight on some of the ugliest aspects of human nature—pettiness, cynicism, self-obsession, vitriol. We find these traits in her characters across the board, and those who veer from this standard are noted for their irregularity. Whether it’s a spunky teenage girl or an ungrateful husband, the dialogue in translation is natural and engaging, and each character reads with a distinct voice; descriptions are elevated by clever word choice, from a “galumphing figure” to “laparotomized remains,” and each paragraph is a newly vivid scene.

While the women of Hit Parade of Tears occupy the traditional feminine roles of wives, mothers, and sexual objects, they are not held to stereotypical ideals of femininity when it comes to their emotions and motivations, which makes this a thought-provoking and relevant read for feminists interested in non-Western perspectives. Women lead the stories in Hit Parade of Tears—with their desires, their passions, and their fears—and the men often read like props to the women’s narratives, whether that’s a self-obsessed husband, an ex-lover, a wannabe sugar daddy, a sacrifice, or a younger brother. Men’s bodies are constantly on display and under scrutiny—balding, thin, hot, or literally cut open from the stomach and hung like an ornament in a medical facility—and they rarely have any part in moving the plot forward.

The men in the protagonists’ lives belittle them and take them for granted, but the stories paint them in all their egoistic ways. In the eponymous “Hit Parade of Tears,” we spend the majority of the story listening to the thoughts of a man born over 150 years prior, who hit his prime in the 1960s and 70s. He talks down on his wife and her job archiving that era: “She’s jealous of me, he thought. She’s seething because she couldn’t take part in my youth like someone from the same generation could.” Come to find out, she’s been alive just as long as he has—they even dated briefly a hundred years ago, but he, solipsistic and self-absorbed, forgot, and he can’t imagine her experiences living up to his. Suzuki’s fiction is explicit in its critique of men’s treatment of women—hypocritical, predatory, and strikingly uncool, Suzuki’s men believe they have the upper hand in their relationships. Behind this belief, Suzuki’s women pull the strings, using the hands they’ve been dealt (as housewives, as sexy schoolgirls, as the repressed desires of a depressed woman) to their benefit.

But while Suzuki’s stories are decidedly women-centered and critical of the societal norms of her time, it’s just as easy to say that Hit Parade of Tears fails a modern, Western feminism. The stories are rife with misogynistic commentary—a character’s “withered” breasts are just another signifier of her pitifulness, and in a pair of girls, “the fat one” only looks “uglier and more ridiculous” after applying makeup. In “Hey, It’s A Love Psychedelic!”, the main character talks with her male friend about another girl “like she [is] more product than person.” Like men’s, women’s bodies in Suzuki’s fiction are always up for discussion, comparison, and disparagement, by men and by women. This treatment is occasionally acknowledged by the characters themselves (“Damn, I’m such a bitch”), but not punished or condemned—rather, the insistent misogyny on display in these stories seems to suggest that misogyny saturates the worlds Suzuki wrote about, and that a woman’s misogyny is just as unremarkable as that of a man.

Suzuki was controversial in her time and likely will be now (though for rather different reasons), as new readers accustomed to Western feminism discover her work and find ableist, fatphobic, and misogynist rhetoric a near constant. As one Goodreads reviewer for Hit Parade of Tears puts it, “In a modern atmosphere, that no longer has a place in literature.” To be honest, though, if we cleanse this collection of its offensive and insensitive characters, we will be left with very little. The protagonists of these stories are not ‘good’ people—the best moral character we see comes from a group of literal outlaws, and some of that group still wants to kill a baby.

Izumi Suzuki was writing in the 1970s, when Western feminism was being imported to Japan, and she—like many people—was not sold. That’s not to say she wasn’t progressive. In her own words (in translation), “There is something wrong with our present society, and I can’t stand [science fiction] written by people who don’t understand that . . . Even when you’re talking about some future society, if you write with full faith in our present world, then nothing changes, you just end up with the same ideas we already have.” While Suzuki’s work may be in tension with some of the ideals of Western feminism, this tension does not arise due to ignorance on Suzuki’s part. Suzuki was familiar with Western feminism and she had little patience for what she saw as efforts to blithely ignore the realities and problems of the current moment. Her work must be understood in the context of her life as a social critic, her work in reinventing science fiction in Japan, and the history of Japanese feminist and queer studies. Critiques of Suzuki’s work—which there are surely space for—should be approached with an understanding of the history of ‘feminist’ science fiction literature in Japan, rather than a purely Western perspective. As Suzuki’s work is translated into English for a modern, anglophone reader, we have an opportunity to look at Japanese and Western literature in conversation.

Feminist science fiction literature from the West in the 1970s saw writers imagining feminist utopias—worlds wherein women are not restricted by gender roles or, in some, even by the presence of men, such as Joanna Russ’s The Female Man (1975). While similar explorations of female-led worlds appeared in Japanese science fiction during this period, these ‘feminine’ utopias were not necessarily in response to or in line with Western ideals. Among these works was Izumi Suzuki’s 女と女の世の中 (1977), in translation by Daniel Joseph as “Women and Women” in the 2021 collection of Suzuki’s work, Terminal Boredom. In this story, men are kept separate from women in “residential zones,” while women date, marry, and raise female children together in sapphic relationships (though these relationships explicitly mimic heteronormative dynamics). In premise, this story mirrors the separatism often found in the feminist utopia narratives common in Western science fiction of the same era, but Suzuki’s protagonist, Yūko, finds herself unsure of her world once she discovers a boy outside of confinement. Even after he assaults her—confirming the danger men pose—she cannot return to her prior contentment with a female-led life. Neither hopeful nor condemning, Suzuki’s take on feminist utopias—and perhaps more broadly, Western feminism itself—is one of ambivalence.

Scholar Mari Kotani, in translation by Miri Nakamura, puts it best: “Suzuki’s . . . works disintegrate the power structure that produces marginalization with phrases like ‘only for women’ or ‘because she is a woman.’ It is only through this process that one can begin to think about what constitutes ‘femininity.’” It would be a mistake to claim that the narrative control these women have is due to some inherent quality of being women, because there is no such thing as an inherent female character. While there are women who are passive and shallow, as well as those who are kind and naïve, women are just as likely as men to be selfish, violent, and judgmental—it’s this dimensionality that truly frees the women of Suzuki’s worlds. It’s of note that, in Japanese women’s literature of the time, women characters who embodied stereotypically female negative traits (promiscuity, bitchiness, vanity) were often cast as villains that enforced existent gender norms. However, throughout Suzuki’s stories, these characteristics are not only acceptable, but also stand alongside masculine-coded traits as necessary to experiencing the full range of life.

Accepting—perhaps even embracing—the worst of human nature is a theme best seen in the six-page short “Full of Malice.” The unnamed main character enters a medical facility in search of her brother, who had been brought there at five years old twenty years prior. Around every corner is another smiling face; it’s an idyllic, if somewhat unnerving, scene, until she rounds a corner to find her “little brother, still five years old . . . Encased in glass, his belly ripped open.” She screams, and awakes to find her head much lighter—chopped half off. The doctor informs her, “We took the liberty of removing your vitriol—your malice. We do the same for everybody here. That’s why they’re all so happy, and why they can handle true freedom.” The doctors eventually remove the rest of her brain, and the protagonist is left a happy, malice-free husk. She spends the rest of her life staring at her little brother’s corpse in the sunroom. In the final remarks of the story, she says, “I never even think about leaving this place anymore. Now that all my malice is gone.”

Malice—in other words, what we’re not supposed to feel; in other words, what we don’t want to feel; in other words, virulent and toxic, loathing, rage, apathy, grief, regret. It’s the lack of emotions like these that leaves the protagonist smiling up at her brother’s remains, unable to feel revolted. It’s the bliss of keeping your eyes and mouth shut. Considering the time and context of Suzuki’s writing, as well as her own public stances on society seen above, we can read this pure, malice-free, bleak world as an extension of her thoughts on feminist utopias—again referencing Mari Kotani: “For Suzuki . . . separatism [in feminism] produces both a sense of comfort and a simultaneous sense of lack.” Without men, there is something missing. Without malice, there is something missing. Suzuki’s stories, stripped of their malice, would be similarly inert. At a time when so much literature feels sanitized, when we are reevaluating what has a ‘place’ in literature, Suzuki’s voice is boldly abrasive. Her characters are judgmental and malicious, sexual and murderous and apathetic. They are filled with life. In Hit Parade of Tears, this is not a coincidence; it’s our malice that lets us burn.

Bella Creel is an English teacher in Himeji, Japan, and a blog editor at Asymptote Journal.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: