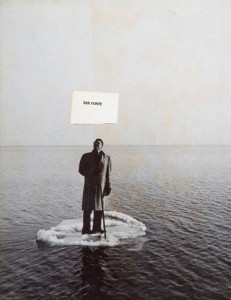

After a two-year hiatus during the COVID-19 pandemic, Carnaval do Brasil was poised to return in all its colorful pageantry across the country this past February. Yet, flooding across Brazil’s Sao Paulo state forced many cities to cancel their scheduled festivities as hundreds flee their homes. In a month that has witnessed devastation on a large scale stemming from catastrophic natural disasters, from the deadly quakes in Turkey and Syria to forest fires in Chile, it can feel like an unrelenting onslaught of uncontrollable circumstances. Enter the work of Guga Szabzon, a visual artist and educator from São Paulo, Brazil, whose works speak to the impossibility of naming experience even as they offer a way to keep the world “safe between . . . pages.” In the first installment of a new series spotlighting the stunning visual content from our archives, we revisit our interview with the artist from the Fall 2018 issue.

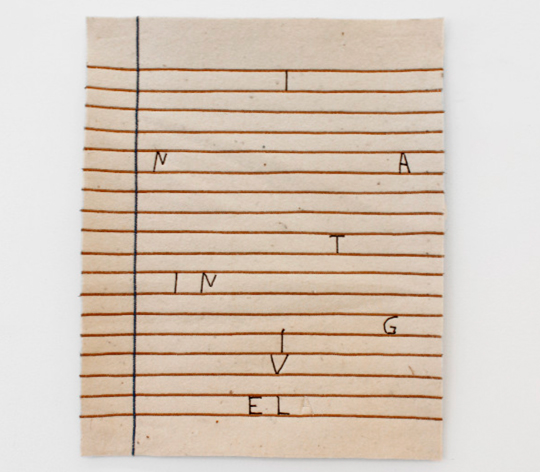

The lines in a notebook, in general, have a clear utility: to organize the text, to make the text comprehensible with a clear and sequential reading. I’ve never really followed that rule, but I always opted for notebooks with ruled pages. I discovered after some time that what attracted me to this choice was not having a blank page waiting for me. The lines were already a design. As time went by, I realized that the organizational forms of the world interest me. And I realized that there was a similarity between ruled lines and the coordinates of a map. Both have latitude and longitude. One organizes a text and the other organizes space.

The sensation that I had with this project was the same that I had with my notebooks. My own world kept safe between the pages. Everything I had lived. How many stories fit inside a notebook? How many stories can be written on the blank pages? An entire world awaiting the next word.

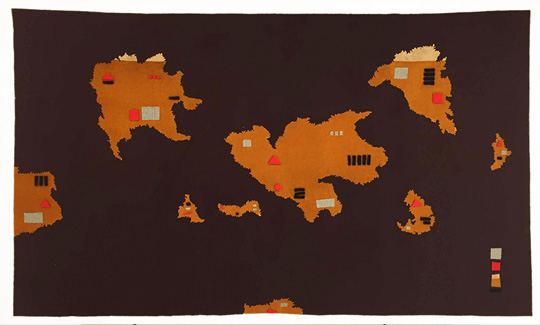

Maps have been present in my projects for some time. When I was in college, my grandfather was getting rid of many of his books, and I took a huge stack of old atlases that had no other use; they had become obsolete because of the simple fact that everything in the world is always changing. Borders disappear, rivers spring up, cities grow, and the atlases are there, trying every year to account for everything, an ever-frustrating endeavor to organize, categorize, and explain the world in a book. For me, atlases were an attempt to represent the truth, a book that people could access to understand the true distances between one person in South America and another in Europe. In this book, people could learn about the depths of the oceans, about the ocean currents, the winds, the climate of each country. What the forests are like, about all the animals that live within them. We could talk about how many inhabitants there are in each city (imagine how crazy that would be, we would have to publish thousands of books every second). Atlases served, then, as a means for us to be sure that we ourselves were on this earth, everyone at some reference point. With this in mind, my first project was, using those maps, to remove all the names that appeared with a utility knife. Thus, they were no longer places, they were no longer possible to find. There was no further explanation.

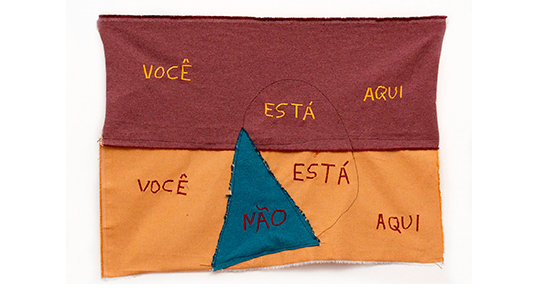

After this, the map project unfolded in different directions, placing labels as a way of piling names on top of names, joining different territories in one solitary space, merging boundaries, creating new countries, new destinations, and other experiences.

When I’m walking down the street, I look at the nooks, at the ground, at the trash. When I dream, I pay attention to the images and absurd situations that I create. When it’s cold and I get a little warm, I think about the fabric on my skin. When I fall in love, when a relationship ends, when I organize the clothes on the clothesline by color, when I’m waiting for the bus—it is quite intense. I go a little crazy with so many images, so many feelings. I think to myself that everything could be potential material to be transformed. Every single thing, when taken seriously, is transformed and becomes eternal. It’s not that this is what always happens, on the contrary, those are rare and magical moments.

Translated from the Portuguese by Sarah Booker and Robert Noffsinger. Images courtesy of the artist.

Revisit our interview with Guga Szazbon and accompanying portfolio in a full-screen immersive slideshow here.

*****

Read more on the intersection of visual art and literature in the Asymptote Blog:

- The Wish as Transaction: On Deena Mohamed’s Shubeik Lubeik

- Visual Noise: Alejandro Adams on Screen Languages

- Flowing Speech: On the Complexities of Audiovisual Translation