Many are likely to be acquainted with celebrated Mexican writer Yuri Herrera by way of his novels, but in this latest collection of short stories, the author extends his brilliance to a vast array of disciplines and subjects. With elements of politics, philology, science, and storytelling, these tales not only display the talents of a master craftsman of language, but also an endlessly inventive imagination, a sharp humour, and a fascination with how this world—and other worlds—work. As our Book Club selection for the month of February, we are proud to bring to our readers this riveting constellation of ideas and dimensions.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

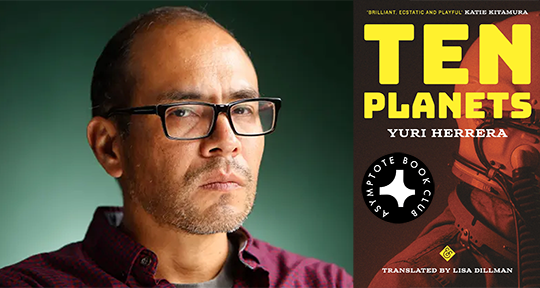

Ten Planets by Yuri Herrera, translated from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman, Graywolf Press, 2023

One of the simple pleasures of science fiction is the possibility of escapism—into another reality, galaxy, or dimension beyond our reach. In the vibrant imagination of Yuri Herrera, however, abandoning the rules of our world allows for a speculative fiction that unites fantasy with lucid reflections on contemporary culture, experimenting with the bounds of genre to create something uniquely Herreran. The twenty stories that comprise Ten Planets, astutely translated by Lisa Dillman, combine the philosophical musings of Borges with a characteristic humour and warmth, inviting us to explore the twenty-first century and beyond.

From a house that plays tricks on its inhabitants to a bacterium that gains consciousness in an unsuspecting Englishman’s gut, Herrera’s imagination works on scales both large and infinitesimally small. The stories cover distances ranging the interplanetary and the interpersonal while retaining a sense of warmth and wonder at the world, expanding beyond genre conventions with a wry humour that packs a surprising punch. Dillman, in an insightful translator’s note, reflects on her personal reservations towards science fiction until she read the works of Octavia E. Butler, within which she saw how science fiction can shake off the coolness of rationality by turning its attention to very human problems, the ones we experience on a day-to-day basis. Herrera’s work is exemplary of the best of the genre in that sense, joining Butler, Ursula K. Le Guin, and others in his ability to imagine a dazzling array of worlds that each speak to our contemporary anxieties—from technological surveillance in ‘The Objects’ and the absurdity of the terms and conditions tick-box in ‘Warning’, to real stories of alienation and societal marginalisation in ‘The Objects’ (two stories bear the same name—because why not be playful?).

This sense of play exemplifies Herrera’s attitude towards boundaries—be they generic, geographic, or linguistic. Dillman has collaborated with Herrera on numerous translations of his work (this being the fifth book appearing in her translation), and she notes that Herrera’s writing ‘is nothing if not experimental and everything he writes is something of a departure.’ Instead of being guided by overarching tropes, science fiction is Herrera’s springboard for a ludicrously inventive imagination. This reflects broader trends in Latin American fiction today; while the Anglophone market pays eager attention to a work’s generic classification, Spanish-language writers are more likely to toss out the rulebook and play with genre, as is the case with Herrera’s playful speculative fiction.

The kaleidoscopic possibility of Herrera’s work reflects his literary influences; some have cited Italo Calvino’s stories as one referent, but a clear precursor is Jorge Luis Borges, master of short fiction, and Herrera pays homage to one of Borges’ most iconic stories in ‘Zorg, Author of the Quixote’. Borges’ version has Pierre Menard, a Frenchman, accidentally writing Cervantes’ lines from scratch, while Herrera amps up the absurdity factor in introducing Zorg, a shy writer whose principal hobby seems to be ‘rapturously touching his own tet’. (We never learn what a tet is, but Herrera’s wry sense of wit invites a humorous interpretation.) In this fiction, it’s Zorg, not Pierre Menard, who creates Don Quixote, Sancho Panza, and Dulcinea. And just like Borges—and Cervantes—who love to play with literary self-referentiality, Herrera’s characters make metatextual comments on his own enterprise:

“I don’t really know what you were expecting me to say,” she finally said. “You know how predictable I find speculative fiction. It’s formulaic, it’s contrived, it’s adolescent.”

Herrera has an ability to break the literary fourth wall with a sly wink to the reader, and as such, Ten Planets is a book that knows how to laugh at itself. His writing is simultaneously highly literary and full of adolescent humour (such as the ‘tet’), but this balance of registers only enhances the pleasure for the reader.

While the humour carries us along, the emerging political themes allow the reader to engage with the text on multiple levels. In an interview for the Times Literary Supplement, Herrera commented: ‘With every word you pick you are making an aesthetic, ethical, and political decision, all at the same time. You are positioning yourself in regards to hierarchies, power and the powerful, and what language is useful for.’ And in addition to the more explicit references to our digital age and all its dangers—the lack of privacy, the sense of surveillance, the surrender to forces beyond our control—Herrera has a real concern with language, the raw material of his craft. The story that opens the collection plays with the Biblical creation myth; in Genesis, God speaks the world into existence, and thus language constructs our world. Herrera subverts this notion by depicting entropy, the end of things, wherein language falls away from its referent, leaving our protagonist in a ‘wordless euphoria’.

Some of the references to language are highly playful; in ‘The Cosmonaut’, as a reference to the nineteenth-century pseudoscience of phrenology, Herrera presents a character who knows how ‘to read a nose—its grammar—as well as the secret that this particular nose was revealing.’ Or in ‘Appendix 15, Number 2: The Exploration of Agent Probii’, the lingua franca of the planet in question turns out to be copulation (perhaps a nod to the adolescent humour of Zorg and his speculative fictions). But once again, this playfulness belies a very serious concern; as Dillman mentions: ‘A love and respect for language is evident in everything Yuri writes, and language itself is regularly a theme. He constantly pushes linguistic borders. He neologizes, he rescues archaic words, he recovers words and expressions in disuse, he verbs nouns.’

While reading Ten Planets, the continuous insistence on wordplay recalls the work of a different craft—that of translation. Dillman matches Herrera’s stylistic shifts with aplomb, to the extent that in a collection of twenty stories, each one reads as unique and different. She responds to his inventiveness with creations of her own; the translator’s note highlights fascinating examples of Herrera’s neologisms, and her quest to capture them in a similarly inventive English. The ‘iota’, which seems to be a unit of space-time, recurs throughout the collection, and it is only through Dillman’s sensitivity to Herrera’s idiom—and in this case, his repeated use of ‘ápice’—that we get to delight in an English that shares the aims of Herrera’s Spanish.

Translating Spanish produces its own unique challenges, just as each language in translation—and each author’s command of their language—is unique. But re-reading Herrera’s stories, I was struck by the sense that these stories invite translation. The names of his characters draw from Spanish, English, and the intergalactic; the settings of his stories span the human intestine to the farthest reaches of outer space; his language fashions Spanish anew with both inventions and innovative uses of familiar words. Borges is a great writer of world literature because his works draws on the singular and the universal, the Argentine and the global. Herrera, too, certainly deserves such a reputation. Straddling the intimacies of the interpersonal and the expanses of the universe, his imagination deserves to be enjoyed by a wide spectrum of readers. And thanks to Dillman, readers of the Anglosphere now get to indulge in his boundless creativity.

Georgina Fooks is a writer and translator based in England. She is the Director of Outreach at Asymptote, and her writing and translations have been published in Asymptote, The Oxonian Review, and Viceversa Magazine. She is currently completing a doctorate in Latin American literature at Oxford, specialising in Argentine poetry.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: