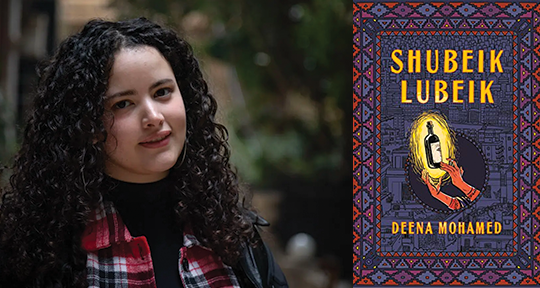

Shubeik Lubeik, written, illustrated, and translated by Deena Mohamed, Pantheon, 2023

Shubeik Lubeik, Deena Mohamed’s ingenious graphic novel⸺whose title in Arabic means “Your Wish is My Command” ⸺seamlessly synthesizes Egyptian culture and history into an epic-scale social commentary, invoking direct parallels to the act of translation. Taking place at a Cairo kiosk, with “[its] banners, red iceboxes; [and] brightly colored snacks,” the vivid setting embodies both global capitalist influence and quaint elements of old Egypt, establishing a quirky but believable fictional venue where, among other sundry goods, bottled wishes are sold.

Originally self-published in Arabic as a ninety-page comic book, Shubeik Lubeik won the Best Graphic Novel prize and the Grand Prize at the 2017 Cairo Comics Festival. Mohamed then translated her work into English and sent it to Anjali Singh⸺a literary agent and translator of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis⸺who promptly agreed to represent Mohamed. After undergoing extensive developments in subsequent Arabic and English versions, Shubeik Lubeik is now released by Pantheon in its current 518-page incarnation, a magnificent trilogy of connected stories spanning over six decades of Egyptian social history—from 1954 to the present day. Kiosk owner Shokry⸺the seller of three bottled first-class wishes inherited from his pious father⸺serves as the central link to three narratives: Aziza, an illiterate, impoverished widow who refuses to be cowed by Egypt’s corrupt bureaucracy; Nour, a privileged, non-binary college student beset with mental illness; and Shawqia, a plucky matriarch whose life is marked with migration and health issues.

In the first story, Aziza is stubbornly resisting the state’s attempts⸺with its latent bias couched in convoluted wish licensing regulations⸺to deprive her of the ownership of a first-class wish, purchased with hard-earned savings from years of labor. While Aziza initially bought the wish to achieve material comfort, her dogged refusal to give up her wish—which lands her in prison—becomes a moral struggle against the state’s unjust process.

The second story, while also affirming individual choice, takes a different approach. Nour, steeped in material comfort but plagued by chronic depression, cannot decide if they deserve happiness. As a wish studies scholar, Nour is vexed by the gap of knowledge between the wish and its fulfillment. Since a disparity can exist between a wish⸺formed by exigent circumstances⸺and the irrevocable effects of its realization, Nour fears that their wish for happiness won’t alleviate, but perpetuate their exile in an emotional zombie land.

In the book’s third section, in contrast with Nour’s epistemological fear as to a wish’s outcome, Shokry accepts his own lack of knowledge in deference to God’s will. Similarly, his father, an archeological guide who believes that wishes are blasphemous to men of faith, is forced by his British superiors to accept three first-class wishes as payment, but refuses to use them to alleviate the consequences of his family’s displacement from their ancestral home—caused by expansive British excavation of Egyptian artifacts and sanctioned by corrupt local officials. Both Shokry’s and his father’s refusal to use wishes as problem-solving instruments can also be defined as moral choices based on faith.

If Shokry and his father’s views reflect the anti-wish position, then Shawqia’s experience with life-threatening but preventable endemics⸺also depicted in Shubeik Lubeik’s third section⸺represents a compelling argument for the pro-wish position, with its feminist and corporeal angle to counter the religious, male-centric view. Specifically, when recounting Shawqia’s family history, Mohamed touches on schistosomiasis, a common parasitic infection from the Nile that used to afflict Egyptian rural poor, and hepatitis, caused by the careless reuse of glass syringes to treat this infection.

Most importantly, all the linked stories in Shubeik Lubeik embrace the stalemate struggle between external, seemingly deterministic forces (sexism, poverty, disease, intolerance) and individual choice (personal ethics, philosophical skepticism, resourcefulness). In the various narratives, each character’s pursuit of well-being starts out as a private endeavor—but similar to Mohamed’s thoughtful mediation of her locality (Cairo, Egypt) and the world, each is also given time and space to consider freewill and determinism, and the relationship between the expression (or suppression) of their wish and their environment. In sum, the concept of earned agency at the center of these in-depth explorations is the most riveting aspect of Shubeik Lubeik, echoing the central idea of One Thousand and One Nights: telling a good story means to translate one’s reality, and in doing so, destinies can be shaped, and demises deferred.

Thus, while evoking the wish-granting trope of One Thousand and One Nights to address real world concerns, Shubeik Lubeik embodies the multifaceted essence of translation. Mohamed eloquently observes that, since the comic is a visual artform, the inherent sensation of mediated reality comes from reading the caption or dialogue for each picture frame. Narratively, while Shubeik Lubeik defines a wish as a commodity, marketed as “the only product [whose] limitation is the owner’s imagination,” there exists an implicit but unavoidable tension between the wish and its execution. As Mohammed illustrates—in an apparent nod to W.W. Jacobs’ “The Monkey’s Paw”—if the jinn has unbound discretion, or if the wisher is not sufficiently specific in their wish expression, the translated result is more likely to be disastrous.

Since wish translation, like any form of translation, is as much about fidelity as betrayal, there are layers of related inquiries that flow from the novel’s core premise: the instability of language and its dependence on context or usage; the influence of religion and politics on the concept of wishing; the struggle between preordained fate (similar to a translator’s adherence to the original text) and freewill (rejection/revision of the status quo); and last but not least, the legacy of colonialism evoked by unreliably executed wishes, sarcastically coined by Mohamed as “Delesseps” after Ferdinand Marie de Lesseps⸺the 19th-century French diplomat who developed the Suez Canal to further France’s colonial ambition, with utter disregard to the health and safety of Egyptian workers.

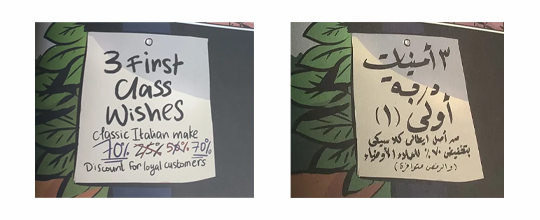

As wealth and power can determine how one’s desire is implemented, wishes are classified in Shubeik Lubeik as first-class, with the most generous interpretation executed by a refined, submissive jinn (who translates the wisher’s desire to its closest approximation and thus would exact a high purchase price); second-class wish (for any material object roughly equivalent to the wish’s purchase price, executed by a sufficiently reliable jinn but not meeting first-class standards), and third-class wish (as established above, a Delesseps or worthless wish, attached to an untamed or malevolent jinn with “bad-faith interpretation,” conducive to a devastating outcome).

In Mohamed’s complex fictional universe, the question of deference/fidelity becomes a knotty issue under different lenses of inquiry. To kiosk owner Shokry, a devout Muslim, the idea of selling first-class wishes for profit poses a serious metaphysical conundrum, since it encourages man’s resistance to God’s will and allows a jinn⸺no matter how polite or deferential⸺to play God. But to Nour’s wish ethics professor ⸺whose interest resides in secular humanism⸺the practice of using any wish, first or third class, is morally suspect, since it allows a wisher to bind a jinn⸺a “sentient being”⸺to a broad spectrum of unregulated transactions. The definition of a good or bad jinn/wish translator also depends on context, for a deferential jinn, stripped of all agency and bound to a first-class wish, is analogous to a conscripted slave, while an unruly or “malevolent” jinn, capable of subverting the wisher’s intention, may be called an artist or a revolutionary.

By framing the wish in a transactional context, Mohamed also extends her postcolonial critique to include insidious aspects of capitalism and the post-9/11 geopolitical landscape. The translation of “Delesseps/third-class wish” to other linguistic contexts is bitingly apt, such as Satangbalim (사탕발림⸺ “sugar coating” in Korean), un rouillé (“a tainted bit” in French), Sh*t tinnies (“worthless money/worthless cans of beer” in Australian slang), Duffers (“thieves who sell worthless products, or steal and alter the brandings on cattle,” in both British and Australian slangs), and Abu Khaybeh/Abu Khaybar (خيبة أبو ⸺ “snafu’s father” ⸺possibly a feminist epithet mischievously devised by Mohamed, or a phonetic pun alluding to the name of a suspected terrorist of unknown affiliation, detained indefinitely in Yemen by extra-national forces while the Trump Administration considered his jurisdiction under the Guantanamo military tribunal).

Before the print publication of Shubeik Lubeik, Mohamed had already made her name with Qahera, a feminist web comic where the question of agency/freewill appears to be a given, since the eponymous superheroine (evoking the Arabic word for Cairo, which also means “victorious”) is modeled after what Mohamed calls the “corny” tradition of superheroes in American comics. But Mohamed subverts the straight-forward heroism with satire to decry the hide-bound sexism of Egyptian culture, political censorship, Islamophobia, as well as the blinkered views of mainstream Western feminism; despite being called a superheroine, Qahera does not feel exempt from oppression, and often wonders if she has done enough to save others.

Similarly, as author and translator, Mohamed wonders about the issue of agency in translation. By creating Qahera almost simultaneously in English and Arabic, she explored, in real time, the tension between a creator’s freedom and a translator’s subconscious desire to adapt to the reader’s cultural expectations. In one unpublished strip, a stand-in for Mohamed expresses her dilemma of publishing in English; while it gives her direct access to a global audience, English is not “just a language but also a sign of privilege, class and wealth.” When her characters are made to speak in English, Mohamed wonders whether they become paler versions of their Egyptian selves. Translation into English also carries the risk of perpetuating both authorial patronization and audience’s entitlement, as if one is “making work for children who cannot understand the difference in culture.” Still, despite these reservations, Mohamed prefers to translate her own work as a way to map out her cultural comfort zone.

Unlike the online immediacy of Qahera, Shubeik Lubeik followed the traditional process of print comics, and took seven years to complete. While Mohamed still makes linguistic or narrative adjustments depending on whether the intended audience is Egyptian or Anglophone, this time, instead of approaching agency as a narrative given, Mohamed painstakingly illustrates her stories from the vantage of her characters’ disenfranchisement, with the concept of wish mediating the private with the public. Her characters, initially deprived of certain needs, eventually attain either relief or self-awareness by undergoing an exhaustive ethical inquiry that balances desire with responsibility. This approach, despite the book’s magical elements, seems more thoughtful and democratic than the overtly cautionary message of “The Monkey’s Paw,” where an old man, by thoughtlessly expressing a wish for extra income, must suffer the horrendous consequence of his son’s death.

By addressing her characters’ specific concerns against a chaotic social environment, Mohamed expands the role of translator to include advocacy, thus continuing a Cairene tradition that began in 1879 with James Sanua, a satirist who poked fun at corrupt politicians beholden to foreign powers, and recently taken up by Magdy El Shafee, who founded Cairo Comics and is hailed as “the godfather” of Egyptian graphic novelists. In the years leading to the Arab Spring, El Shafee’s graphic novel Metro: A Story of Cairo (originally published in Arabic in 2008 and translated to English by Chip Rossetti in 2012), boldly exposed Egypt’s crumbling infrastructure and affirmed the resourcefulness of its hidden civilian forces, symbolized by Cairo’s vast underground metro tunnels. While the lure of instant gratification exists in both Metro and Shubeik Lubeik, both El Shafee and Mohamed, as Egyptian artists and activists, understand that the struggle for transcendence/freedom is an arduous, long-term endeavor, not unlike efforts undertaken by countless translators toward translation.

In sum, Mohamed, via her monumental graphic novel, deftly plumbs the layers of human hope and desire to illustrate our eternal yearning for a perfect world and a perfect text, which is nevertheless driven by our confusion and imperfect knowledge. Shubeik Lubeik’s profound essence seems best evoked by Kurt Gödel’s mysterious statement that blends reason with metaphysics, freewill and fate, the personal with the universal:

The meaning of the world is the separation of wish and fact. Wish is a force as applied to thinking beings, to realize something. A fulfilled wish is a union of wish and fact. The meaning of the whole world is the separation and the union of fact and wish.

Thuy Dinh is coeditor of Da Màu and editor-at-large at Asymptote Journal. Her works have appeared in Asymptote, NPR Books, NBCThink, Prairie Schooner, Rain Taxi Review of Books, and Manoa, among others. She tweets @ThuyTBDinh.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: