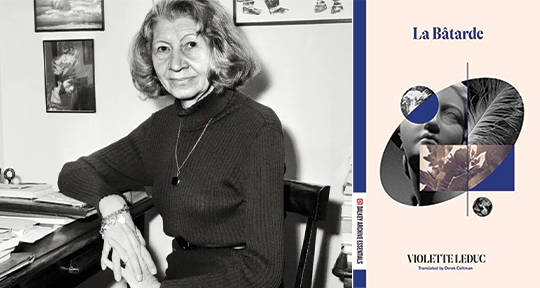

La Bâtarde by Violette Leduc, translated from the French by Derek Coltman, Dalkey Archive Press, 2023

“. . . very often, women think that all they need do is to tell their unhappy childhood. And so they tell it, and it has no literary value whatsoever, neither in style, nor in the universality which it ought to contain. So there are many, many autobiographies which publishers reject . . . Very disappointing . . . to think that as long as they’re women telling their story it will be interesting. . . . [but] there are extraordinary cases, like that of Violette Leduc who, exceptionally, was wonderfully successful.”

—Simone de Beauvoir, La Revue Littéraire des Femmes (March 1986)

“Being a woman, not wanting to be one,” Violette Leduc writes about her mother, Berthe, in La Bâtarde [The Bastard]. Perhaps she is speaking about herself as well, the reader takes a guess, which later in the autobiography is—spoiler alert—confirmed. Originally published in 1964 by Éditions Gallimard in Paris, La Bâtarde was translated into the English by Derek Coltman (who has translated two of her other works) as La Bâtarde: An Autobiography, and released the following year by C Nicholls & Company in the United Kingdom and by Farrar, Straus & Giroux in the United States. Over the years, at least two new editions have been published, and this year, we are given a new edition to this bestselling French autobiography from Dalkey Archive Press.

“Being a woman and therefore condemned to the miseries of the feminine condition,” echoes Simone de Beauvoir in the foreword. Like Hannah Arendt, Frantz Fanon, Robert Brasillach, and Richard Wright, Leduc is considered a historical contemporary and political protege of Beauvoir (although ecofeminist-biographer Françoise d’Eaubonne disagrees, stating that Leduc never subscribed to Beauvoir’s philosophy or politics). It may have been, however, more than that; newly discovered letters—two hundred and ninety-seven of them—have revealed Beauvoir rejecting Leduc’s repeated romantic advances.

This autobiography is unapologetic—particularly so, as Laetitia Hanin deems, because while its predecessors within Francophone women’s literature, like the memoirs of George Sand and Marie d’Agoult, sacrificed to self-mythification, Leduc did not apologise for writing the story of her life. Beginning in northern France, the author reveals a childhood spent under WWI German occupation, where the government’s rationing of food is so insufficient people resorted to stealing cabbages from the back of carts. Two maternal figures among a neighbourhood of women raise her: her mother, Berthe, with whom she has an extremely agonising and suffocating relationship (“You were all I had, mother, and you wanted me to die with you”); and her grandmother, Fidéline, “an angel” who loved her “in passionate silence.” In her youth, as an “unrecognized daughter of a son of a good family,” she yearns for a paternal figure, but she will never know her father André, a man whose dominant quality is anonymity: “It is a strange moment when you gaze questioningly at an unknown figure in a picture and the picture, the unknown figure, is your nerves, your joints, your spinal column.” Further contemplating on her lineage, Leduc writes, “I reject my heredity.” This is particularly true with her maternal relationship, when in the later years Leduc would say: “Her absence was a relief; I was oppressed by her return.” Eventually, she would burn André’s photograph along with his death certificate. She writes, “My birth is not a matter of rejoicing.”

Dubbed as “France’s greatest unknown writer,” the questions one must ask about Violette Leduc are: What was—and is—her place in the Francophone literary canon? And how did that shape her autobiographies—particularly La Bâtarde? Elizabeth Brunazzi lines her among “the canons of ‘high art’ or ‘elite culture’,” on par with Brasillach, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, and Ezra Pound. A biographical play about her, La terre est trop courte, Violette Leduc (1982) by Jovette Marchessault, is considered “the most visible presence of female homosexuality in Quebec theater.” She is listed among canonical lesbian writers Gertrude Stein, Ivy Compton-Burnett, May Sarton, and Maureen Duffy, as well as canonical French autobiographers and memoirists Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Stendhal, André Gide, and Jean Genet. Paradoxically, however, Leduc is also an outsider from the mainstream canon. Even within political writers like Luce Irigaray, Colette, or Virginie Despentes, Leduc has been “occluded and fallen out of the dominant archives in the process of the Americanisation of both [European, mostly French] queer and feminist theories.” As Beauvoir in the foreword points out, despite Leduc’s talent and even after conquering the bestseller lists, she “remained obscure.”

On a personal level—or shall I say, on the level of autobiographical persona as a textual construct—“[she] was a woman who in spite of her considerate courage and talents never felt secure in love and in writing because of what she viewed as immense handicaps: she was a bastard, she was ugly, and she was a lesbian,” wrote William C. Carter for The French Review. And the literati did nothing, at first, to raise her confidence; La Bâtarde was rejected by France’s highest literary awards—the Goncourt and the Femina—as it was considered to be of “a bastardized genre.” As she admits in La Bâtarde: “I mingled truth with fiction.” However, there are more layers to her separation from the literary elite, according to Natalie Edwards: namely, she writes in the confessionalist, autobiographical genre, and she was indeed widely considered to be a lesbian. Of course, her defiant writing of female sexuality, even in sexually progressive France, was still transgressive. In Le Corps Lesbien (1975), French novelist Monique Wittig incisively cuts through the malignant issue of lesbian invisibility:

[Lesbians have] no real existence in the history of literature. Male homosexual literature has a past, it has a present. The lesbians, for their part, are silent—just as all women are as women at all levels. When one has read the poems of Sappho, Radclyffe Hall’s Well of Loneliness, the poems of Sylvia Plath and Anaīs Nin, La Bâtarde by Violette Leduc, one has read everything.

So, while French gay male writers like Marcel Proust, Gide, or Jean Cocteau “have always been part of the canon,” wrote Jeannelle Laillou Savona, “lesbian writers [like Leduc] and topics have remained marginal and are almost never mentioned in French canonical histories or anthologies of literature . . . [and] are still ignored by mainstream critics in France.”

La Bâtarde is what Jodie Medd in The Cambridge Companion to Lesbian Literature (2015) catalogues as “an autobiographical French bestseller featuring schoolgirl affairs.” This assertion of the ‘I’—in autobiography, in memoir, in confessional poetry—is an assertion of the self, of the person speaking and writing their truth. And the personal—for the historically underrepresented and marginalised—is always political. But could Leduc be categorised exclusively as a lesbian when she was attracted to Gabriel and Hermine at the same time? Her romantic history, as portrayed in La Bâtarde among other autobiographical works, also spells out Maurice Sachs (with whom she lived in Normandy in the happiest time of her life), Nathalie Sarraute, Genet, and of course, Beauvoir. Leduc had both men and women as lovers. As Florence Tamagne in A History of Homosexuality in Europe (2006) pointed out, she “is a very ambiguous personality and her testimony must be seen in context: she goes out with Hermine, but also with Gabriel, and it is he whom she seeks to please by dressing this way.” So who decided Leduc was lesbian and La Bâtarde a lesbian text?

In literature, the bisexual erasure and stigmatisation—the bisexual absences, so to speak—partially stems from lesbian/feminist theory’s tendency to gloss over and “ignore the bisexual content of much of lesbian fiction” and other literary genres. “Bisexual invisibility . . . is standard, with few portrayals of bisexual people, and a tendency for fictional characters who demonstrate potential attraction for people of more than one gender to be portrayed as transitioning between gay/lesbian and straight, or vice versa.” As a reader who identifies under the umbrella term of bisexuality, I find Leduc’s love affairs in her adult life as portrayed here in La Bâtarde —her vicious intimacy with Gabriel, her idyllic passion for Hermine, her fervid devotion to Maurice Sachs—very telling. Bisexuality, a term that can be traced back from South European and Middle Eastern cultures, as well as Ancient Greek and Near Eastern mythologies, is gendered and sexed in varied ways. Leduc is a testament to this framing of desires, performances, and identities that may be unequal, but overlap and co-exist at the same time. The literature of bisexuality, particularly in the late nineties, was grounded on this co-present romantic and/or sexual desire for the feminine and the masculine—or as Virginia Woolf would have it, woman-manly and man-womanly. But building on current scholarship and contemporary terminological consensus, it has now come to mean “sexual desires or behaviours towards other people of more than one gender.” Leduc is therefore bisexual, and La Bâtarde, a bisexual text.

On the textual level, La Bâtarde starts in a rather stilted tone. The first few pages recounting her maternal history were written by Leduc the child—the essayistic I-then, to appropriate from Woolf. The sentences are fragmented, the scenes hazy. Ray Conlogue has asserted that part of the problem in translations from the French “is a French lyrical verbosity that does not work in English.” Perhaps such is true in Coltman’s translation—at least the first chapter. At this juncture, the text partly resembles a letter being read, and partly a monologue no one hears; its language is disjointed and dreamy, unfiltered and unmediated, which may reflect not only the truth passed down to Leduc, but also the accuracy of the memory she remembers remembering. (“Unflinching sincerity, as though there were no one listening,” promises Beauvoir in the foreword.) The reminiscence alternates from a noisy farm of “quarrels, harsh treatment, foul language. The screams of the pig being killed at three in the morning” to a town that “is warm between the half-open shutters, the sea . . . singing a few yards away,” a “lavender blue lamp [that] brings the night.”

However, later on, Leduc seamlessly transitions into an entrancing story, with the death of her grandmother setting things into motion. “Fidéline died and I found my feet.” Gone were her grandmother’s skirt and her “unreal breasts,” her comfort zone, her shield from the cruel world. She also discovers her sexual awakening through a book a playmate brings over, upon which she finds that the concept of heterosexual intercourse and genital masturbation repulses her (“I smelled my fingers, I breathed in the extract of my being, to which I attached no value”)—a feeling further entrenched when she is raped by two neighbourhood boys. Throughout the narrative is an element of betrayal, albeit in a bizarre form. Leduc feels betrayed by her grandmother Fidéline for dying, by her mother Berthe for warning her about the evils of men only to later act against her own advice, by several of her women guardians and caretakers for growing apart, by men who are both hauntingly absent (her biological father) and loomingly present (her stepfather). Betrayal is what propels her through her life, what is necessary for her to evolve.

One can only guess at Leduc’s motivations for writing her life. As she writes, “That is all we shall ever know.” Although she was also a novelist, her childhood preference for real life over stories (“A frog is a frog, a cow is a cow”) explains her veering towards nonfiction; a biography of an anonymous railroad worker seemed to be the first book she actually liked. “Desiring the self,” Michael Sheringham in French Autobiography: Devices and Desires (1993) adds, “the autobiographer must first encounter alterity: other texts, other ideas, other people. . . . primordially, there is inevitable ‘doubling’ which arises when we turn our attention inwards.” For Leduc, the turning inward after her mother asks her, “Are you always going to live in a dream?” would happen—despite it being coerced—years later. “I weep with the passion of a woman torn from her lover’s arms.”

Readers of Leduc will witness a true narrative of a child with feelings of being inadequate, unloved, ashamed, told by a gifted storyteller whose voice demands to be heard and read. Overall, the generalist reader finds a more enriched reading experience when this autobiography is taken along with the biography by Carlo Jansiti, Violette Leduc Biographie (2013) and the Martin Provost biopic Violette (2013), while those with a background in French literature and history may find more meaning to also read Violette Leduc (1985), Isabelle de Courtivron’s mapping of Leduc’s autobiographical project and gender performance, as well as Susan Marson’s Le Temp de l’Autobiographie: Violette Leduc ou la mort avant la letter (1998) which delves further into the author’s poetics.

Alton Melvar M Dapanas (they/them) is the editor-at-large for the Philippines at Asymptote. A native of southern Philippines, they’re the author of Towards a Theory on City Boys: Prose Poems (UK: Newcomer Press), assistant nonfiction editor at Panorama: The Journal of Travel, Place, and Nature and Atlas & Alice Literary Magazine, and former editorial reader at Creative Nonfiction. Their lyric essay has been nominated to the Pushcart Prize and their prose-poem was selected for The Best Asian Poetry. Their latest poems, essays, and translation appeared in BBC Radio 4, Oxford Anthology of Translation, New Contrast: South African Literary Journal, The Shanghai Literary Review, Rusted Radishes: Beirut Literary & Art Journal, and Tokyo Poetry Journal. Find more at https://linktr.ee/samdapanas.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: