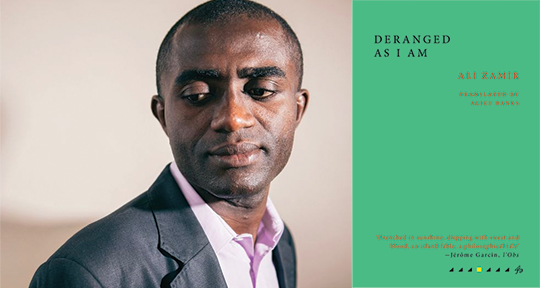

Deranged As I Am by Ali Zamir, translated from the French by Alice Banks, Fum d’Estampa Press, November 2022

In Ali Zamir’s third novel, Deranged As I Am, narrator-protagonist Deranged is an impoverished man, somehow surviving on the paltry daily wages he manages to earn through hard labour at the docks from transporting goods and cargo, who keeps himself aloof from his fellow workers who make fun of him, using his clothes as a calendar: “Deranged as I am I have only seven ancient shirts in all. Seven pairs of trousers and seven pairs of shorts all pocked with holes and on each of them a day of the week so I don’t forget remaining me that I shouldn’t wear the same outfit twice you see?!” The novel itself begins intensely in medias res with Deranged trapped in a confined space, wounded and on the verge of death, his limbs tied up as flies swarm around him. His crying out, while exaggerated, highlights a jagged agony.

The rest of the narrative recounts the incidents that led to this low point, with Deranged refusing to keep quiet and hunker down in the face of his many painful oppressions: “Let me make you understand this loud and clear as long as my heart beats your ears will bleed they will bleed until my soul is dizzy lest I disappear with a stream of tears in my charmless eyes.” Situated at the dizzy intersection of various vulnerabilities, he has minimal hope of having his voice heard or his exploitation compensated, because to the “angels of darkness,” as he calls the flies that represent his numerous tormentors, he is nothing but a speck of dirt that they can wipe away and then go about their day. The readers therefore become interlocutors, individuals who would not easily dismiss him or his story, and give a patient ear to his list of troubles and problems.

The novel is short at about eighty pages, and the action of the story takes place over the course of a few days. Deranged is a dockworker in the port city of Mutsamadu, capital of the island Anjouan, Comoros, in Southeastern Africa. The narrative does not call attention to its location, beyond the plenty references to the tropical weather, and in turn the characters of the novel do not really have names, but epithets, much like Deranged—for example, the other dockworkers, such as Sleeper and the Pipipi (Pirate, Pistol, and Pity), and Deranged’s neighbor, Nuisance. In Zamir’s French, the language features rare words and is linguistically fascinating, traits that Alice Banks’s superb translation also possesses. Comoros is of course a multilingual nation with the most common languages being a group related to Swahili, termed Comorian or Shikomori. The other prominent languages are Arabic and French, the former because Islam is the predominant, official religion and the latter because Comoros used to be a part of the French colonial empire until its independence in 1975.

Language, as mentioned before, is one of the strongest aspects of Zamir’s novel. Sentences are long and so are the paragraphs, the former usually without any punctuation to follow the rhythm of speech as Deranged directly addresses the readers while he narrates his misfortunes. Given to philosophizing, he is not one to vacuously wax eloquent, but instead raises intense images born out of his own struggles and suffering. There are places where the language adopts a unique, very awkward, figurative language in the context of the body, whether the “eiffel tower [that] could be seen rising proudly in [Deranged’s] threadbare trousers,” “a snake [that] had come alive in my pants,” or a host of other similar euphemisms that sound off. The book has an unmistakably masculine tilt that affects how characters interact and behave, especially the few and far between women who remain little more than binaristic stereotypes.

Freud, first identifying the psychological dichotomy in his male patients called the Madonna-Whore complex, wrote: “Where such men love, they have no desire and where they desire, they cannot love.” Through this lens, men see women as either virginal objects of desire or despoiled and immoral sluts. They were either saints or sinners, nothing in between. Over time, this particular term has come to be associated more with the male gaze in general, even if the ones gazing are not men. Deranged As I Am seems almost a textbook example of this phenomenon in operation. There are just the two women characters—neither actually named and known only through referents—in the short novel, and while Deranged himself does not seem to be attracted to either of them, the binary is established through a nebulous authorial gaze, that transfixes these two women and places them on either side of an artificial division.

The husband of the first woman and Deranged’s neighbor, Nuisance is extremely jealous and is the root cause of why his wife lost all her friends: “. . . [T]hough she went to great lengths to satisfy her husband he didn’t give two shits so he would publicly humiliate her . . . Any woman who visited her was scared off by her husband accusing them of acting as a messenger for his wife’s hypothetical lovers and she [then] ended up shutting herself in her house and losing her lust for life.” When he sees her exchange a few words with Deranged, he mutilates her genitals by biting them off at night and is hauled to jail after other neighbours create a ruckus. Ever the long-suffering wife, she begs the police to show leniency and leave her “darling husband in peace,” even going to the point of threatening to join him in jail if he is not freed immediately. There is clearly no regard for herself and her own well-being.

On the other hand, the wife of the trader is a woman of means and station who is clearly quite independent of her husband. From the start, she is sexually interested in Deranged not because of any of his inherent qualities, but because it would be a scandalous slap in the face of her absent husband who seems to prefer his mistresses over her: “I admire your body. It’s a beautiful chariot perfect for transporting me to a wonderful world.” Deranged is perturbed by her sudden forwardness: “I felt her fingers slip over my chest and when she trailed them out I felt them linger there making spider legs on my weak chest and I had been transported beyond myself and . . . oh my poor snake was running wild in its cage!” A dissatisfied housewife looking for sex, she takes advantage of the power imbalance to assault him when they are alone again.

If the former is a Madonna, then the latter is a Whore. Nuisance’s wife is clearly suffering from her husband’s abuse and depredations, yet she is entirely beholden to him. Perhaps because she does not know any better, or because she is more afraid of a life without him than of his casual cruelty, or because she has nowhere else to go, she stolidly bears with it and arranges her life according to his whims. The trader’s wife does seem more “enlightened,” but her privilege and freedom seems to result only in her abusing her social position to get what she wants. She has a son—Nuisance and his wife are childless—and wealth, but she is stuck obsessing over the corporeal. While it is a departure from the usual in that it is her doing the relentless pursuing and not Deranged, her sexual forwardness is continuously derided. She threatens to have Deranged killed for refusing to sleep with her and spreads rumours that he raped her.

When all is said and done, I must return to the narrator’s pet phrase, which also happens to be the title of the book and his own name: “Deranged as I am.” Between its common parlance meaning of mad or insane and Deranged’s constant breaking of the fourth wall to implore the readers to trust him, all that we have read and know to be true is casted into doubt. Hence, it is easy to notice the number of times Deranged adds an ellipsis followed by “I am sure of it” at the end of his assertions. This frequency is particularly high towards the end, as Deranged is markedly helpless and flustered when faced with his benefactress’ sexual advances: “Listen to me carefully dear friends this happened! I know my memory is cloudy . . . Yes dear friends I have to scrape through the shit filling my brain to tell you this story but believe me dear friends believe me!”

Must he constantly reiterate the truth value of his story because no one is liable to accept his testimony due to his class position and mannerisms? Or because he is truly deranged and all of this exists only in his head? After all, he himself says in the beginning: “Well maybe there is a grain of truth in that yes a drop of madness I would say but completely crazy?” Zamir never clarifies for us, which makes it all the more disturbing, given how Deranged ends up near dead after being lynched as a suspected rapist and is subsequently entrapped in a random shipping container headed towards an unknown destination. His parting exclamations—“Devilish devilry! What a farce! What a masquerade!”—bring the novel to an end, underlining its initial framing as a tragicomic misadventure. However, in its intricate exploration of exploitation and poverty, the tone hints at something much darker than what Jérôme Garcin calls “an island fable.” It is Rabelaisian slapstick for everyone else. For Deranged, life.

Areeb Ahmad is editor-at-large for India at Asymptote and books editor at Inklette Magazine. Most of Areeb’s writing can be found in his bookstagram, a true labour of love. His reviews and essays have appeared in Scroll.in, Gaysi, The Chakkar, Mountain Ink, and elsewhere.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: