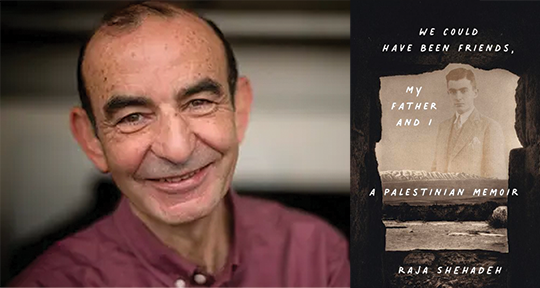

We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I: A Palestinian Memoir by Raja Shehadeh, Other Press, 2023

In Postcolonial Memoir in the Middle East (2012), Norbert Bugeja defines the memoirist as operating “within that representational chasm . . . in which the memoirist’s chosen interpretation of a space or preferred schema of memory come to be reconfigured against the received facts of traditional ideological geographies and vice-versa.” In the harrowing We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I: A Palestinian Memoir, Raja Shehadeh shows he is no exemption to this friction between fact and memory. A Ramallah-based human rights lawyer with several acclaimed memoirs (one received the 2008 Orwell Prize; another was adapted into a stage play) and scholarly essays (covering topics from international law to theatre criticism) to his name, Shehadeh is a cosmopolitan, peripatetic writer and addresses the topic of his personal history and homeland with wide-ranging expertise. According to Jonathan Cook in Disappearing Palestine: Israel’s Experiments in Human Despair (2008), Shehadeh “is perhaps the most knowledgeable critic of Israel’s labyrinth of legislation in the occupied territories.” In addition to enacting activism through his writing, he also founded al-Haq in the 1970s—a Palestinian organization at the frontlines in peace negotiations and in providing legal aid to Palestinians.

In We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I, his eleventh book of non-fiction, Shehadeh foregrounds the Nakba—the catastrophic aftermath of the 1948 Palestinian war. But a better appreciation of his works necessarily invites a discussion on the milieu of where he is writing from—both ethnopolitically and aesthetically. Ethnopolitically, the memoir centres the land dispossession, drone warfare, and strategic erasure of Palestinians perpetrated by the Israeli military government—as well as the treacheries committed by Palestine’s former coloniser, the Ingleez, Britain, and even neighbouring nations like Jordan and the League of Arab States. Aesthetically, on the other hand, the writing evokes other articles of “resistance literature,” such as those concerning Partition or occupation, as well as the larger body of Arab political essays and political memoirs that permeates Shehadeh’s œuvre: his powerful storytelling emanates from the kind of clearsighted prose afforded by forthright reportage.

Conor McCarthy favourably compared Shehadeh to Edward Said as being “more directly political,” evidently a departure from show don’t tell (a hackneyed chestnut propagated by workshop cultism because there should be, in descriptive writing, room to explain, to tell). Shehadeh takes advantage of the power in exposition even as he plays with form; the narration and the way the chapters are organised as somewhat non-linear and non-chronological, jumping from one particular time and place to another, but remain always guided by both reminiscence and research.

The memoir begins with a recollection of his father, still alive in his office. From there, he goes earlier and earlier in the timeline, unearthing ancestral and political histories with an occasional nod to the present. This conscious and deliberate “disorganisation of the text in ‘spatial’ terms” presents a technique that reflects, as Bart Moore-Gilbert theorises, “the geographical dislocations historically enforced on Palestinians . . . since the patterns of public events and private life repeat themselves ad nauseam under Occupation.” Unlike the structured plots of fiction, in nonfiction, there can only be the author’s thought process and consciousness as organising principle.

Also an expert storyteller within place writing and travel literature, Shehadeh treats this memoir as an evocative paean towards a landscape that can never be recovered. The “arboreal and celestial imagery,” as Bugeja depicts, has been mastered not only by Shehadeh but also other Palestinian writers like Samih al-Qasim, Mahmoud Darwish, Mourid Barghouthi, Sahar Khalifeh, and Ghassan Kanafani. Why is there an ubiquity of this style? Studying the border as imagery in Israeli-Palestinian film and literature, Drew Paul proposes that “[e]ncounters with checkpoints, walls and other borders frequently produce experimental, fantastical and fragmented aesthetics.” This memoir is indeed full of boundaries, walls, and borders—metaphorical and literal and liminal—sometimes traversed with force, sometimes avoided at all cost, but always interconnected.

As in the case of contemporary nonfiction, at least two layered narratives—the personal and the political, the scholarly and the experiential—are braided in this memoir, and in Shehadeh’s previous autobiographical works. In Postcolonial Life-Writing (2009), Moore-Gilbert argued how Shehadeh’s 2002 memoir Strangers in the House: Coming of Age in Occupied Palestine reflects not only of the Israeli Occupation but also the memoirist’s conflict with his father. Joe Cleary, in Literature, Partition and the Nation State, also made the case of Shehadeh “repeatedly return[ing] to [this] difficult relationship” in an earlier memoir, Samed: Journal of a West Bank Palestinian (1984). As for We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I, Shehadeh discloses that revelation of the truth—that Israeli police, he suspects, had conspired in the murder of his father and role-played its investigation—“was the most arduous that I’ve experienced.” Because while justice was being denied in the murder, he “was also witnessing the slow transformation of my country and the destruction of our future in it,” alongside the “relentless, ongoing devastation of the landscape brought about by . . . the building of settlements and infrastructure of roads, water and electricity.”

In more ways than one, this memoir is also a mapping of a family saga, tracing paternal ancestors, all revolving around Aziz Shehadeh and exploring topographies long gone: cypress and pine trees, cows grazing on grasslands, mountains and hills and their contours—all of which now belong to the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Binaries between the old Palestinian natural environment and Israel’s built architecture of the new are pronounced as contested religio-racial ecologies—as well as initiating questions of access, mobility, and its root, ethnic privilege. As any sense of place is connected to its people, this memoir, and Shehadeh’s ancestry, is populated with relationships. A contrast of familial characters is on display: Aziz who “thought his father was too cautious” versus his uncle, the “idealist [but] not a risk taker” Boulos; his social butterfly of a grandmother Julia versus Julia’s reclusive husband Salim; the academic Salim versus the politically conscious Boulos; Julia versus Mary, Boulos’ second wife; Shehadeh’s proud, discontented mother versus Aziz, whose mother died when he was three, and who was then raised by an emotionally unavailable stepmother—only to then marry someone equally emotionally distant.

A result of research and the re-creation of that research (from the archives of his father and publicly available materials, interviews with his late uncle and an ex-Jordanian official, correspondences with his siblings, photographs of people and places kept by relatives, scholarly writings on Palestine, as well as court rulings from England, Jordan, and Israel), the memoir underpins itself as a testament of both the remembered and the documented, along with the gaps that only the imagined and the speculated could fill. The form is reminiscent of the Arab diaristic tradition, dating back to 1068 with the Sufi astrologer-mathematician Ibn Banna and his disparate writings of obituaries, incantations, vignettes, formulas, dreams, and poetry. In Shehadeh, the political memoir reveals its potentiality beyond social commentary, as a literature of witness. I theorise that We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I is Shehadeh’s way to myth-invert what he iterates in Strangers in the House: the nostalgic reconstruction of a bygone Palestine to mask a tenuous escapism of present-day realities.

In Writing Palestinian Exile, Maha F. Habib elucidates: “Life for the Palestinian is frozen in time subsumed by the past; such constructs of reality disavow any forward movement subjugating all who experience and come in touch with them to a static, surreal and distorted experience.” But Shehadeh is no stranger to self-correction: “For years I lived as a son whose world was ruled by a fundamentally benevolent father with whom I was temporarily fighting. I was sure that we were moving, always moving, towards the ultimate happy family and that one day we would all live in harmony.” He would eventually be proven wrong. Despite his efforts in protecting Aziz from the dangers of legal activism, his father would be murdered on 2 December 1985. This tragedy would become the pivotal penultimate moment—perhaps even the very impetus behind this book.

Even as he entreats into the past, Shehadeh grapples with the present, illuminated by the before. Often witnessed here is the portrayal of the Occupied Palestinian Territories as sites that hunger for “re-narration to re-possess an identity, and a nation,” thereby setting forth the Palestinian ideological value of sumud: “perseverance, steadfastness, staying put.” As “contemporary Palestinian writers work to resist negation and anonymity,” wrote Rachel Gregory Fox and Ahmad Qabaha in Post-Millennial Palestine: Literature, Memory, Resistance (2021), their “counter-memories, and thus counter-histories . . . resist the limitations imposed . . . by Israeli settler-colonialism and the US administration.” Shehadeh also utilises these counter-memories and counter-histories on a personal level, through a contemporary nonfiction technique known as perhapsing:

Many years later, I have come to realize that the emotions I was experiencing as a result of Israel’s transformation of our world must have been similar to those that my father had experienced in 1948. . . . It must have felt just as incredible to him that this change could happen, and prove to be permanent, as the changes that I was witnessing under Israeli law seemed to me. And yet, we never spoke about this, nor did the similarities in our experiences bring us any closer together.

On lamented epiphanies and authorial blind spots, Shehadeh wrote “There was no second act . . . What hadn’t happened in the first act would never happen. Life moves in real time.” But even this initially proved to be a half-hearted coming into terms, a half-meant facing of the truth. Despite his mother’s prodding, it would take him many years before finally scouring through the rich archives of papers, documents, written correspondences that his father left behind. The last chapters are moving ruminations of the past: more retrospection, less musing of uneasy realisations. (A hint at a sequel is given at the epilogue “To Be Continued,” as he tries to gain access of the Israeli police’s murder investigation “thirty-seven long years” ago.) Regret—glaringly—precipitates in this book, as the could have been in the title insists:

When he died . . . I had to wake up from my fantasy, had to face the godlessness of my world and the fact that it is time-bound. There was not enough time for the rebellion and the dream. The rebellion had consumed all the available time.

And so, “[the] main reason why the love between us remained unacknowledged was me. I was the one who was unwilling,” because, “[t]here was much then that I didn’t know.” Now that’s how regret should be written.

Alton Melvar M Dapanas (they/them) is Asymptote’s editor-at-large for the Philippines. They’re the author of Towards a Theory on City Boys: Prose Poems (UK: Newcomer Press, 2021), assistant nonfiction editor at Panorama: The Journal of Travel, Place, and Nature and Atlas & Alice Literary Magazine, and former editorial reader at Creative Nonfiction magazine. Their lyric essay has been nominated to the Pushcart Prize and their prose poem was selected for The Best Asian Poetry. Find more at https://linktr.ee/samdapanas.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: