After decades of being dismissed as trash or a genre suitable only for children, comic books and graphic novels have begun to gain recognition in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, becoming the subject of serious scholarly interest and major retrospective exhibitions. Comic art now has an established infrastructure, with an annual prize, the Muriel Award, a Centre for Comics Studies (at the Department of Media and Cultural Studies at Palacký University, Olomouc), and an international comic art festival, Frame, in Prague. In the second of our interviews on comic art, Asymptote’s editor-at-large Julia Sherwood asked two of the Centre’s associates and noted experts Pavel Kořínek and Michal Jareš to introduce our readers to this art form and its leading Czech and Slovak proponents.

Julia Sherwood (JS): You and your colleagues have written widely on all aspects of comic art, from reviews to historical and theoretical articles and essays, including V panelech a bublinách (In Panels and Speech Balloons), published in 2015, the first detailed Czech work that summarizes the various theories and concepts around comic art, which you co-authored with Martin Foret. So to begin with, how would you define the genre?

Pavel Kořínek (PK): The million-dollar question, and straight off, too. There are, of course, many definitions of comics, and new ones are being added all the time. We can revel in Scott McCloud’s definition of comic art as “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer”; we can talk about sequentiality and the dominance of the sequential image primarily in the context of print media; we can reconcile ourselves to the fact that there is nothing that can be defined as being specific exclusively to comics; and we can talk about comics as whatever we (or, ideally, some higher institutional authority, by consensus) declare to be comics. After all, we all sort of subconsciously know “what a comic is” (we just don’t know if it’s actually a genre—and in what sense—a medium, a form, or what). It’s only when we look more closely that we begin to encounter more complicated cases: works that may be related to comics, for example, but don’t quite seamlessly fulfill our ideas of what comics are. In our book, we ended up approaching the question of definition as an open-ended challenge: we offered several influential approaches and tried to convey to the reader our conviction that “comics”—while being aware of all that has been said formally and functionally, socially and institutionally—as a genre is something fluid, evasive, and ever-evolving rather than a fixed category. Fortunately. Otherwise, it would have been a staggering bore.

JS: Your monumental Dějiny československého komiksu 20. století (History of Czechoslovak Comics in the 20th Century, co-authored with Martin Foret and Tomáš Prokůpek), published in 2014, details across almost one thousand lavishly illustrated pages on how the turbulent history of Europe over the past century has affected the development of the genre. Difficult as this task may be, could you outline the main stages and how they were shaped by the political events from the early days until World War; under the interwar Czechoslovak Republic, during World War II; under communism; and after its fall?

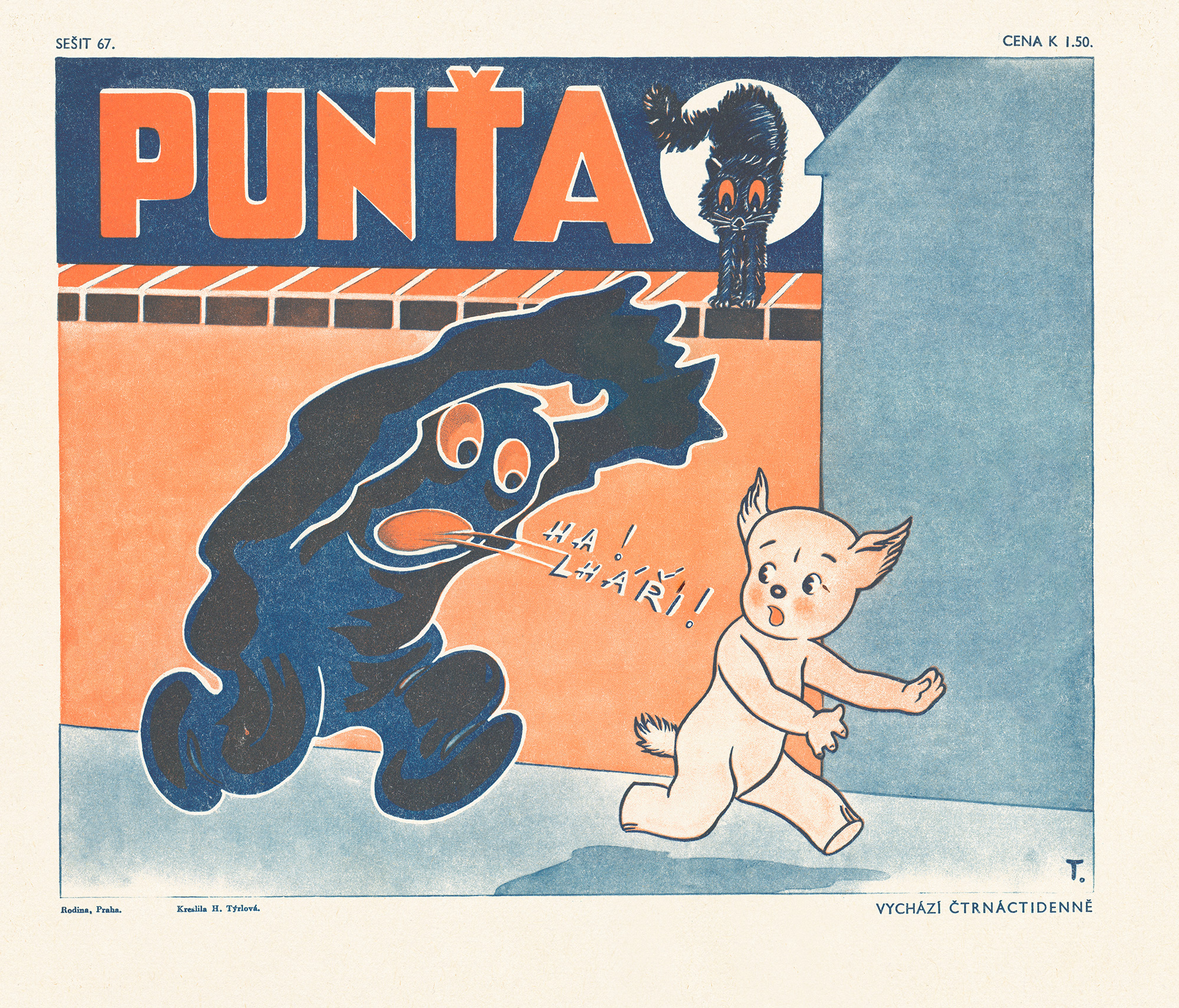

Michal Jareš (MJ): Talking about something that is new and still evolving, such as a “possible” history of Czechoslovak comics, we also have to bear in mind the history of Central Europe as a whole, particularly in our neck of the woods, from the time of Austria-Hungary to the foundation (and later dissolution) of Czechoslovakia. We also have to consider it within the context of the debates and trends that shaped all of twentieth-century art, including the avant-garde. We constantly encounter attempts to understand comics as well as attempts to forbid them, and attempts at innovation as well as attempts to stay within the educational form of comics. So, at the very beginning we can see a clear continuation of the tradition of Central European caricature and thus topics aimed at the adult reader as well. The development of magazines for children and youth spawned a variety of children’s comics featuring humorous animals (such as the children’s magazine Punťa).

HERMÍNA TÝRLOVÁ – COVER OF PUNŤA

A specific feature are the various “strange gentlemen” characters appearing throughout the history of Czechoslovak comics. But at the same time (we’re talking about the late 1930s and ’40s), some important series featuring child protagonists began to appear that have influenced the comics genre in a fundamental way. In terms of periodization, the post-war period may be regarded as a “golden age.” At that time, we also see a number of substantial attempts at addressing the more mature reader (e.g., in the work of Kája Saudek), which exerted significant influence on the Czechoslovak cinema of the period, for example the films Kdo chce zabít Jessii (Who Wants To Kill Jessie) or Čtyři vraždy stačí, drahoušku (Four Murders Are Enough, Darling). The Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, however, brought the development of Czech comics to a halt for a number of years, and it was not until the second half of the 1980s that it resumed. Over the past thirty years, a new way of thinking about comics, its reception, and the discovery of its global context in translation has begun to be rebuilt.

PK: The story of Czechoslovak comics in the twentieth century can be told as a heroic narrative of how comics sometimes survived “in spite of it all”—it is certainly not the only possible narrative, but it is a narrative that has so far dominated the Czech historiography of the comics medium. After 1989, we quickly went through several phases of transformation: following an initial naive enthusiasm, when Czech publishers felt that a few dozen commercially oriented comics magazines could survive in the market (they didn’t), there was a temporary weakening of comics activities in the second half of the 1990s. Since the beginning of the new millennium, we have seen the emergence of an initially subcultural activity in which new comics writers and artists sought new publishing venues, new content, and new genres. In recent years, there has been a relatively significant boom in Czech comics, which has perhaps already achieved a small but recognized niche in the Czech cultural space. Comics are given space in the media, are taught in schools, and can also access public funding in the form of various grants and scholarships.

JS: Anglophone readers may be familiar with one of the founding fathers of Czech comic art: Josef Lada, the illustrator of Jaroslav Hašek’s work. However, his other work is probably less known, as is the work and even the names, of two other towering figures of twentieth-century Czech comic art, Jaroslav Foglar and Kája Saudek. Can you say a few words about these three artists?

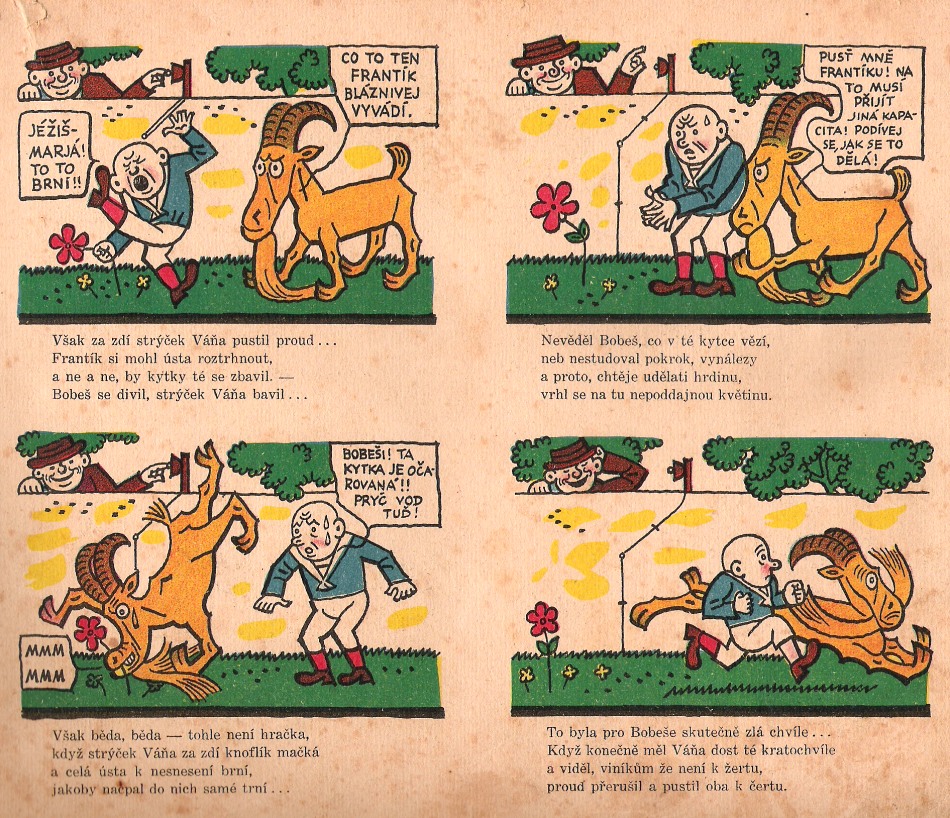

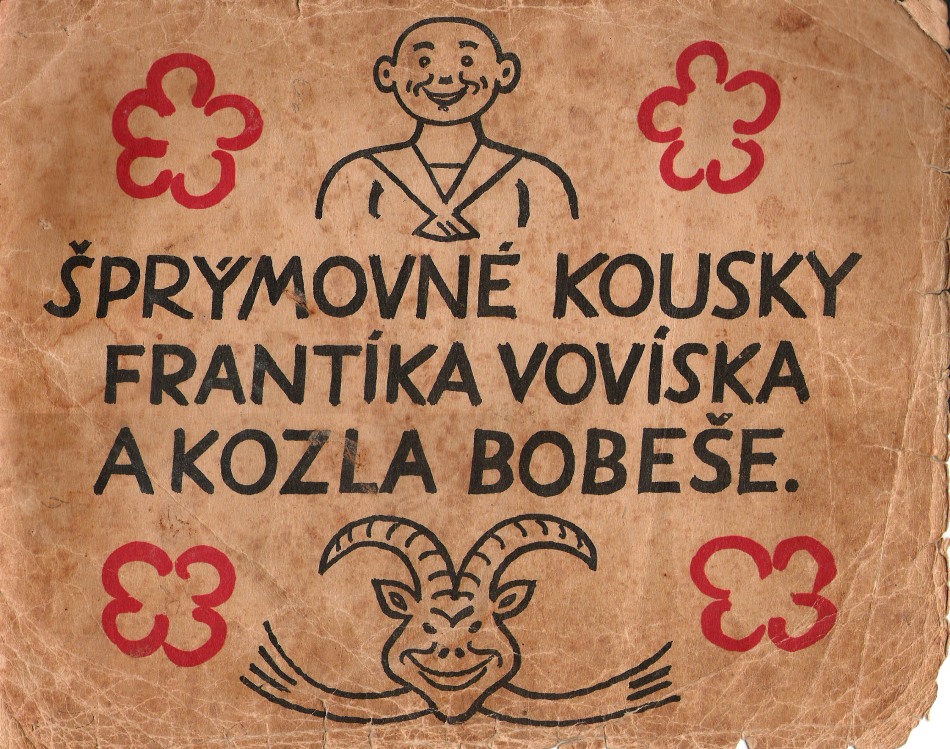

PK: In Josef Lada, Czech comics found its first proponent who fully devoted himself to the sequential form of pictorial narrative with great success; immediately after their completion, Lada’s serials from the 1920s were collected and published as a book, thus breaking out of the temporality and ephemerality of newspaper and magazine publication. Lada’s first large-scale picture serial, Šprýmovné kousky Frantíka Vovíska a kozla Bobeše (The Comical Exploits of Frantík Vovísek and Bobeš the Billy-Goat) from 1922 is sometimes referred to as the first modern Czech comic strip.

To today‘s audience, Lada is definitely better known through his illustrated books (for example, those featuring the tomcat Mikeš), all the dominating Švejk-esque visuals (incidentally also originally from the paracomics series, as Lada originally created his Švejk illustrations for a serial newspaper pictorial adaptation), and the idyllic pictures of the now snow-covered, now blossoming village of Hrušice. In the 1920s and ’30s, however, he was also one of the most important creators in the emerging Czech comics scene.

JOSEF LADA: COMICAL EXPLOITS OF FRANTÍK VOVÍSEK AND BOBEŠ THE BILLY-GOAT

MJ: Foglar was a unique script writer and novelist, who understood a boy’s soul and maintained this focus throughout his work. Together with illustrator Jan Fischer, he created a comic book series called Rychlé šípy (The Rapid Arrows), which influenced Czech comics in a crucial way. With its mix of humour, hyperbole, and the legacy of gothic literature and the scouting movement, Rychlé šípy is wholly original. However, Foglar was far more a writer than a comic book author—after the communist coup of 1948, he was partially banned and, as a result, gained a unique position as a cult author. As for Kája Saudek, he is a self-made and groundbreaking artist who, especially in the 1960s, could compete with the likes of Wallace Wood and other independent comics writers. His completely original vision is still copied and admired today. However, after 1969, Saudek’s work became more and more hollowed out and eventually he began repeating himself. However, this was also because political developments made his position untenable. At the beginning of the 1990s, Saudek‘s style started to lean more towards French influences (the fantasy comic artist Moebius, etc.) and moved from explosive pop art to tendentious eroticism and banality. This was also due in part to his lifestyle and health problems. Nevertheless, Saudek stands out as one of the most exceptional authors in Czechoslovakia.

JS: Given its propensity for adventure, fantasy, and sci-fi, the genre has been traditionally dominated by male authors, although a few women have also made their mark, initially mostly in works aimed at children and young adults. Can you mention the more important female representatives of the genre?

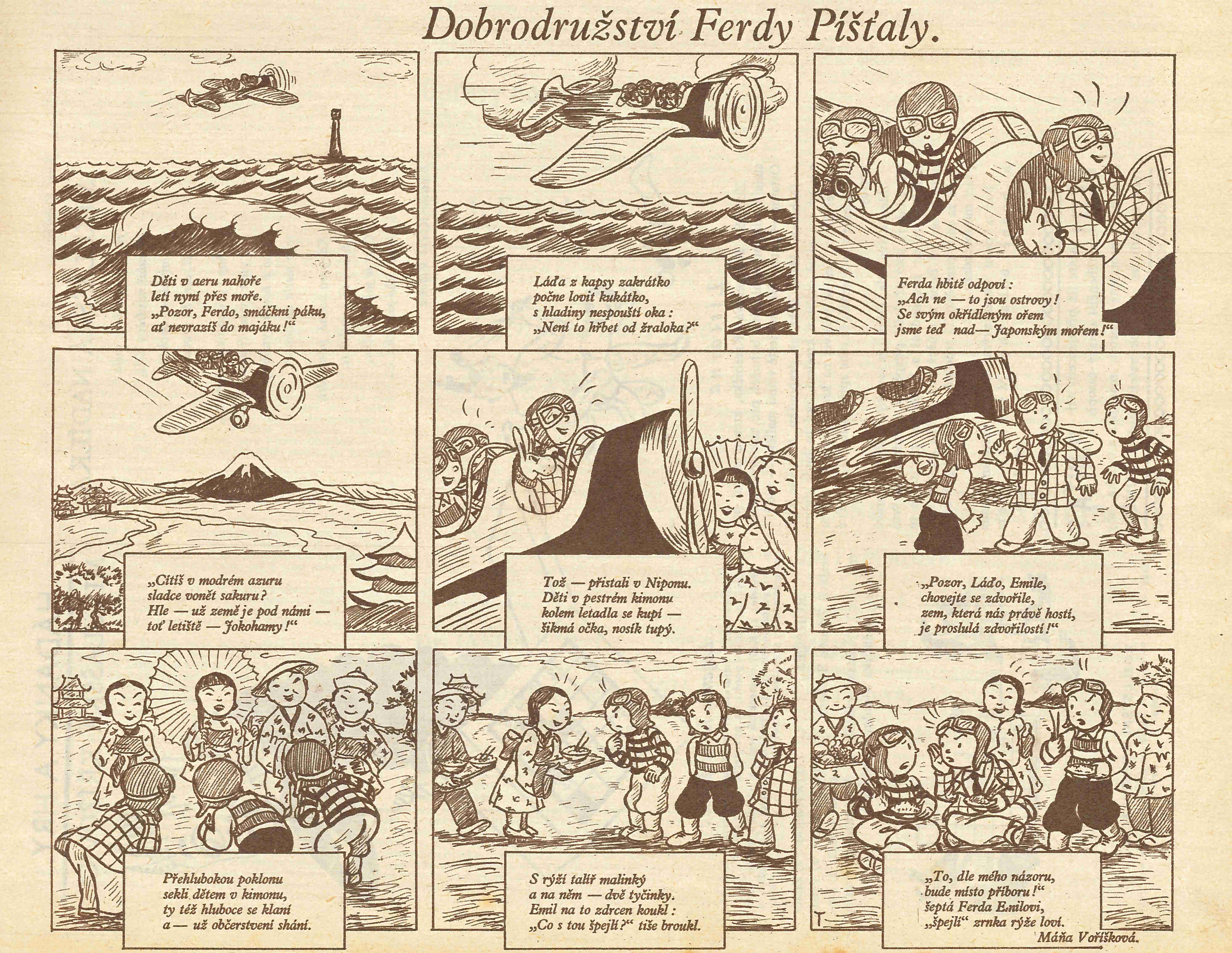

PK: The magazine Punťa, the first really successful Czech comics periodical (1935–1942), relied on female writers; Marie Voříšková, Julie Kaublová, and Blanka Svačinová not only wrote the scripts for the vast majority of Punťa‘s original comics, but also acted as executive editors of the whole ambitious attempt at a Czech “variation on Disney-style comics.” The cartoonists associated with the magazine include Hermína Týrlová, later a famous Czech animator. In the 1960s, Věra Faltová, Eva Průšková, Vlasta Švejdová, and others began to produce their first comic series. They remain somewhat outside the main focus of Czech comics historiography, perhaps because most of their series were aimed at the youngest audience, but I think they will impress anyone interested in Czech comics with the scope and enduring quality of their oeuvre. For example, Věra Faltová created comics continuously for half a century, generating thousands of pages in dozens of different series. In terms of the most recent decades, we should mention Lucie Lomová (see the interview on the Asymptote blog from November 9), who created one of the best contemporary series for children in the 1990s, Anča a Pepík, only to reorient her work towards an adult audience in the new millennium. Then, of course, there are a number of names from the current wave of female Czech comics authors: ToyBox, Štěpánka Jislová, Kateřina Čupová, Lenka Šimečková, among many others.

THE ADVENTURES OF FERDA PÍŠŤALA , MARIE VOŘÍŠKOVÁ (SCRIPT), HERMÍNA TÝRLOVÁ (ART)

JS: Comic books, especially those for adult readers, have more of a tradition in the Czech lands, but there have also been some notable Slovak graphic book artists such as Schek (Jozef Babušek), František Mráz, and Danglár (Jozef Gertli). Can you tell us something about them?

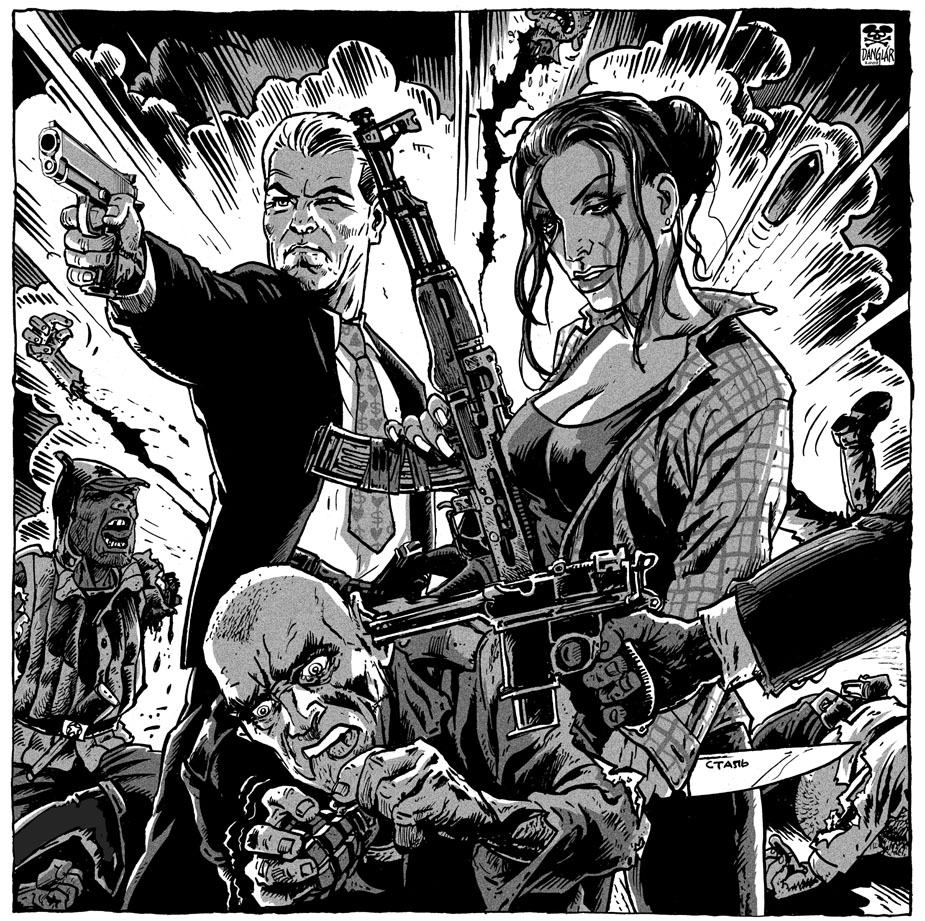

MJ: . . . and let’s also add Božena Plocháňová. Although she was Czech-born, she was one of the most prominent (and prolific) figures in Slovak comics. But, back to the artists you’re asking about: Schek, whose comic strip Jožinko, dieťa svojich rodičov (Little Joey, A Child of His Parents) ran to more than a thousand installments, becoming one of the longest in the history of Czechoslovak comics, was one of the most influential comic artists on the Slovak scene. Schek also created realistic comic book adaptations of literary works, especially of science fiction and adventure. Gertli-Danglár follows him in certain ways, but his work has been much more influenced by pop art, as well as by Kája Saudek, and involves more irony and eroticism, which otherwise have less of a presence in Slovak comics. Danglár is also well known for his political comics and cartoons—and still draws cartoons for the newspapers, while Fero Mráz, another Slovak comic artist, has worked all his life as a teacher and co-publisher of the Slovak comics magazine Bublinky, one of the most important periodicals of its time.

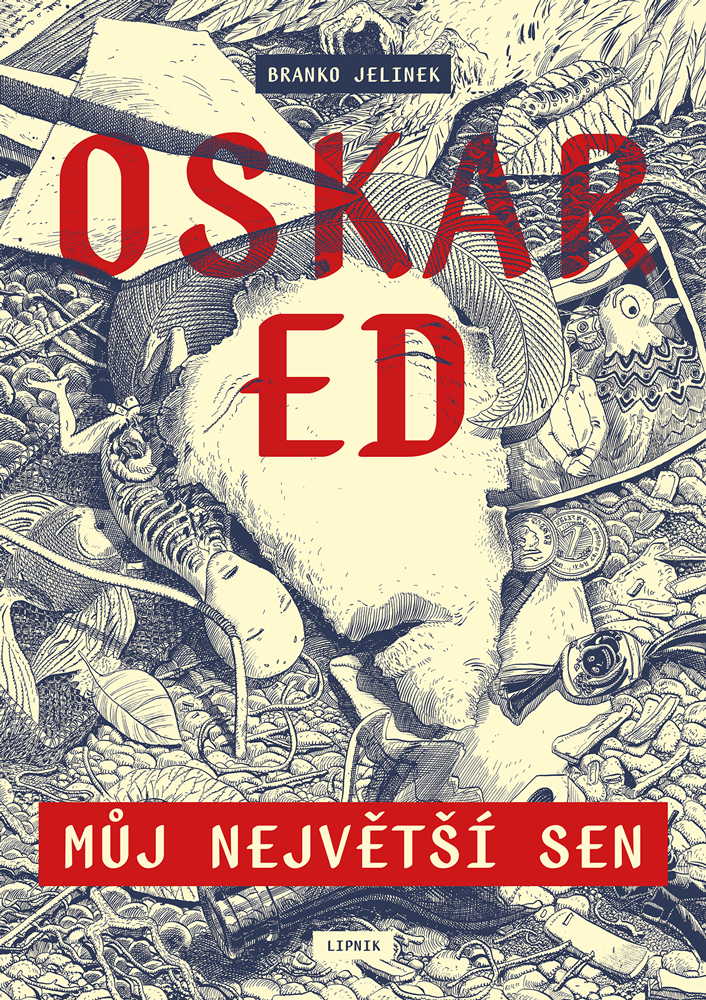

The contemporary Slovak scene is unique, even though it is small, featuring authors such as Daniel Majling (Rudo, Zóna/The Zone) and Branko Jelinek (the Oskar Ed trilogy). The period known as Mečiarism (1991–1998, during the autocratic rule of Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar), has helped to create a specific style, spearheaded by Danglár’s political cartoons. At the same time, many interesting independent activities have emerged, such as the fanzines Your mistake and BB komiks. Many ambitious works are being produced in Slovakia that use comics to explain historical events (for example, the life of one of the founders of Czechoslovakia, Milan Rastislav Štefánik, or the history of the Velvet Revolution of 1989). And, as elsewhere in the world, you can also find comics in Slovakia whose authors tell their own distinctive and original stories, both in terms of historical events and their own experience of parenthood and the problems associated with it.

DANGLÁR: ROGER KROWIAK, © DANGLÁR/LCA

JS: Comic art in the Czech Republic has flourished over the past two decades, with works by Czech graphic artists featured at the Lakes Comic Art Festival in Kendal in the United Kingdom and at exhibitions in Brussels and elsewhere. What are the distinctive features of present-day Czech comic art compared to work created in other countries?

PK: This is a difficult question to answer. I don’t know if I believe in a national specificity of local comics production, so I’m not sure if there is such a thing as “Czech comics” in any other sense than, say, cultural/regional or linguistic. In my opinion, if there is something typical of contemporary Czech comics, it is the fact that there is no distinct artistic style that dominates it. Of course, comics come in all sorts of shapes worldwide, but in some major comics cultures there has traditionally been something of a default mainstream style, some stylistic middle-ground. Czech comics draw on a variety of inspirations: the youngest generation often draws in a style inspired by manga, while some of the older generations combine echoes of Czech adventure comics of the 1970s and ’80s (which were published in small numbers and were relatively limited in terms of page-count, and thus often tended to overuse text and overcrowd the page with tiny panels) with the tired-out dynamism of the American or (Western) European mainstream.

JS: Can you give some of the main themes and most notable sub-genres in contemporary Czech comics?

MJ: As in any national comic variety, we can distinguish between children’s and adult comics. In the former, there is a predominance of animal motifs and characters—i.e., the “humorous animals” genre. Particularly powerful are stories depicting the experience of a group of children. Many home-grown Czech comics are of an educational nature—for example, featuring protagonists who are transported back in time to some historical event by supernatural means. The more mature comics are often marked by a certain nostalgia, or continue the tradition of Jaroslav Foglar’s work. Personally, I’m interested in less straightforward and more enigmatic works, comics with a mystery or irony, infused with greater meaning. Social motifs, as well as eroticism, are a feature of many contemporary comics for adult readers, although they do not dominate. Maybe we’re still missing more storytellers than artists. Or rather: we have many narrators who reminisce and draw, but few professional script writers.

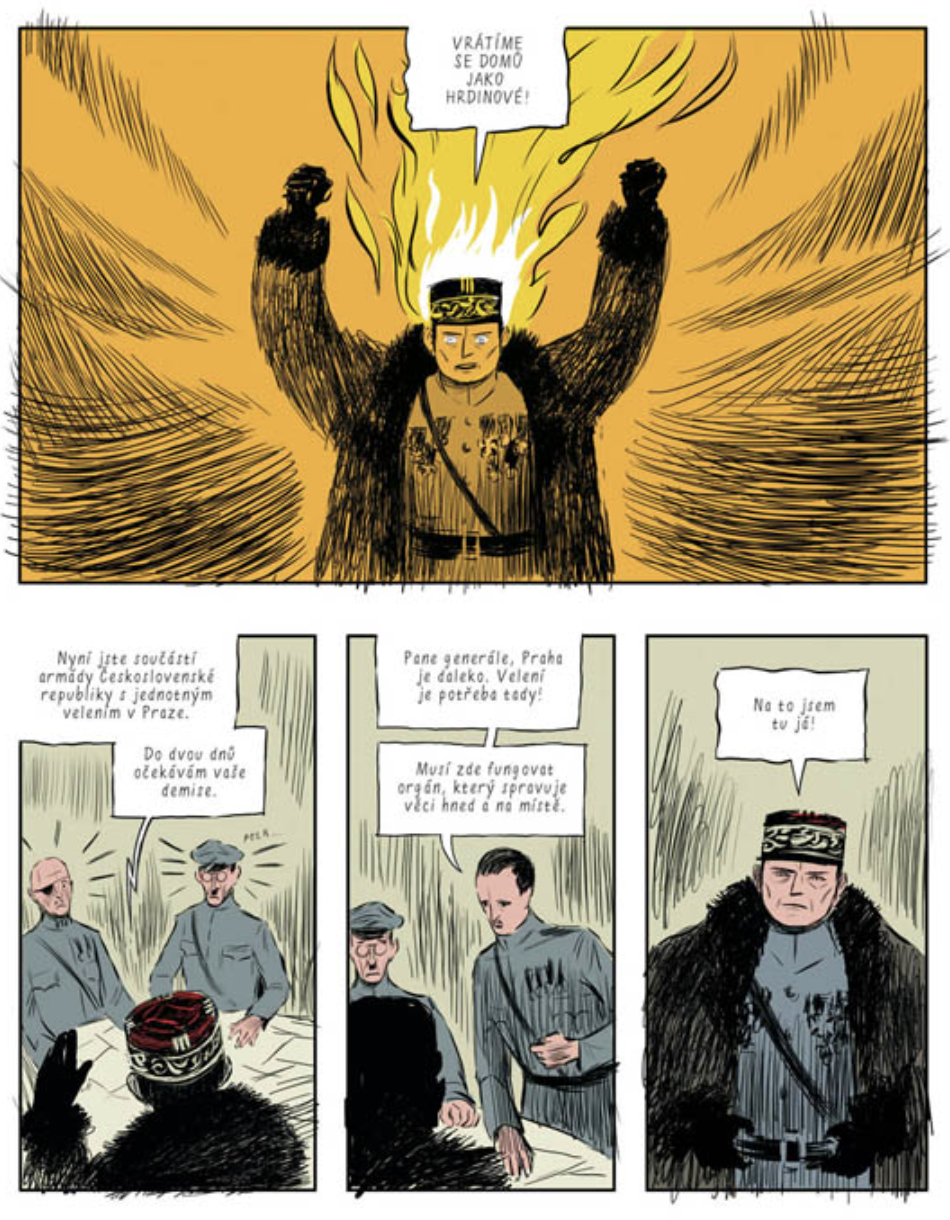

PK: The past few years have been characterised by historical and biographical comics. Interesting works can and do emerge in this genre, and the recent graphic novel Štefánik with art by Václav Šlajch is proof of that, but unfortunately the vast majority of this kind of production offers only very unoriginal, textbook retellings of national history with its established approaches and national failings. Uninspired narratives of national greats, which parents are probably expected to buy for their offspring, make up a good part of the current output.

VÁCLAV ŠLAJCH: ŠTEFÁNIK © VÁCLAV ŠLAJCH/LABYRINT

JS: Despite being increasingly recognized abroad, only a few Czech graphic novels or comic books have been translated into other languages, in particular into English—I am aware of only three, all by the same artist, Jaromír 99: his graphic novel version of Kafka’s The Castle, and two books authored by Jan Novák, Zátopek and So Far So Good. Nevertheless, Jaromír 99‘s most famous work, Alois Nebel (also adapted into an animated feature film) has yet to be translated, as are many other great works by individual artists and artist collectives. Which graphic novels would you like to see translated into English?

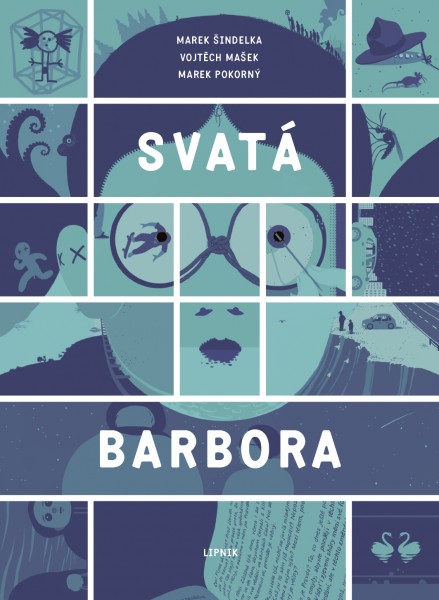

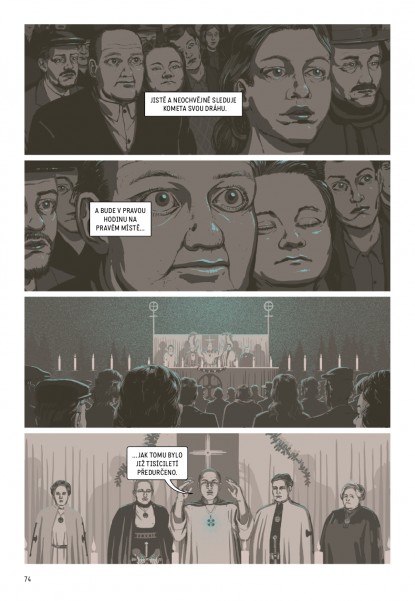

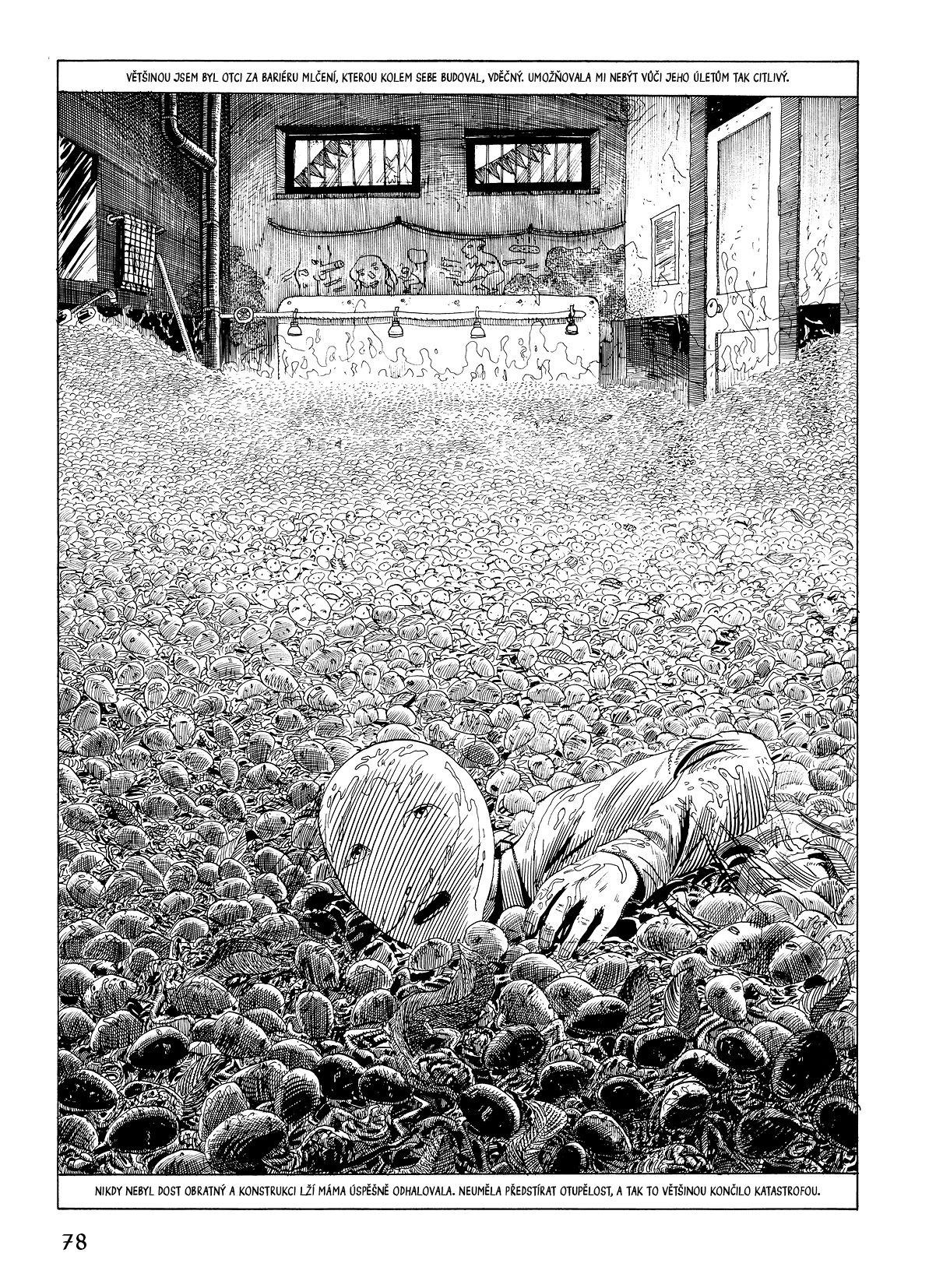

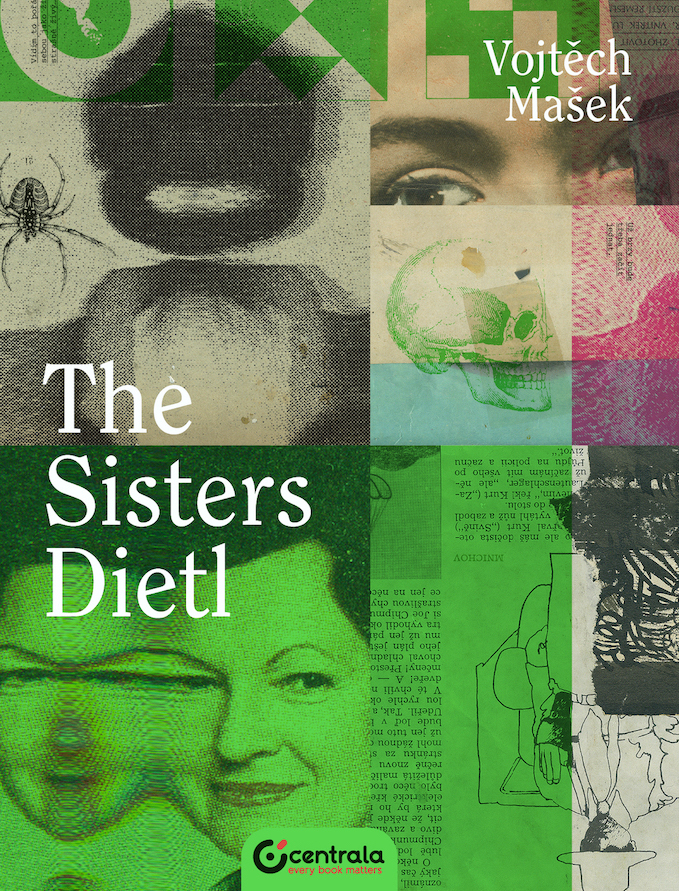

MJ: Svatá Barbora (St. Barbara) by Vojtěch Mašek, Marek Šindelka, and Marek Pokorný tells a typical Czech story, but I think it would also be fascinating for foreign readers. I consider Branko Jelinek’s work on Oskar Ed to be unique: his Oskar Ed trilogy, published 2003–2006 and its 2016 sequel Oskar Ed – Můj největší sen (Oskar Ed – My Greatest Dream). At the same time, I worry that many comic books are often not distinctive enough and thus overlooked in global overproduction. Maybe alternative comics on the border of fine art (like Toy Box, or writers centered around XRX mag or Kix magazine) are original, but they don’t try to be likable and don’t have the opportunity to reach a larger audience; they’re too specific, and even in the midst of the comics community, they’re more on the fringes.

ST BARBARA – VOJTĚCH MAŠEK, MAREK ŠINDELKA (SCRIPT), MAREK POKORNÝ (ART) © LIPNIK)

BRANKO JELINEK: OSKAR ED – MY GREATEST DREAM, © LIPNIK

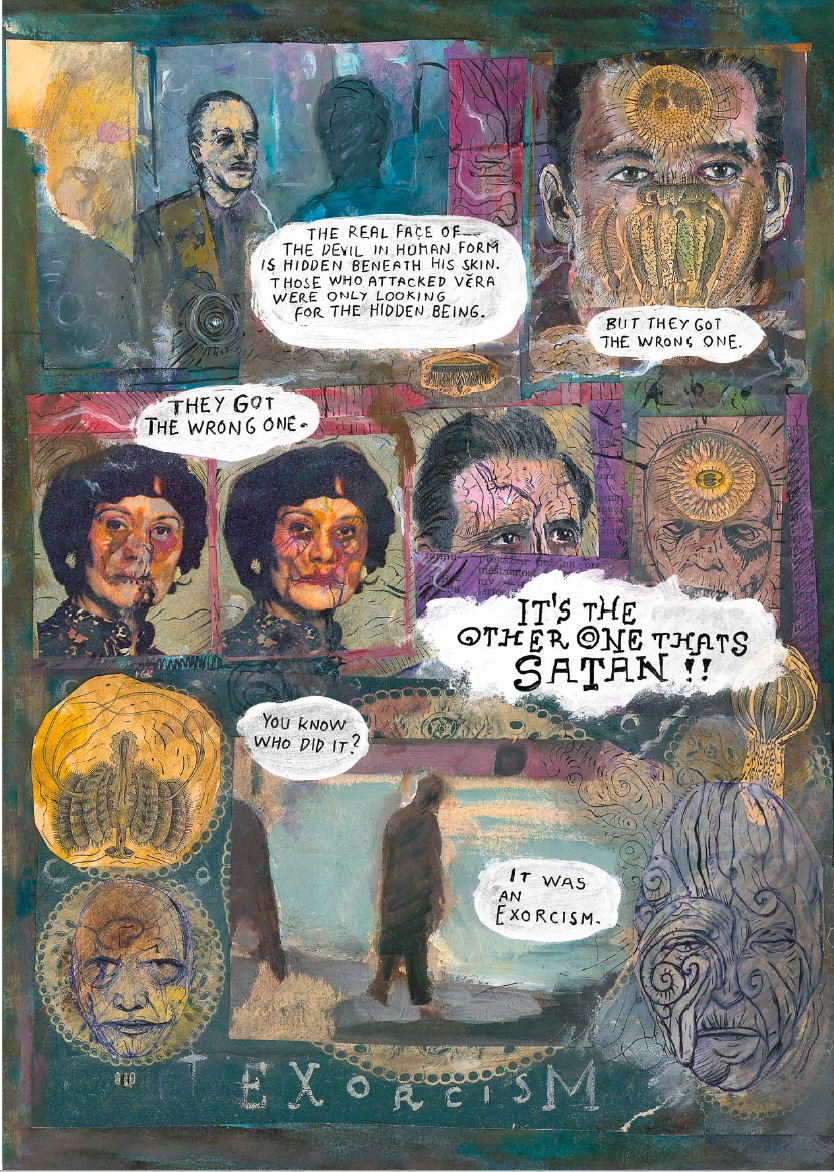

PK: I can only add a few names that I think deserve attention: the graphic novels of Lucie Lomová (Divoši/Savages) should be—and I am pleased to learn soon will be—published in English, as well as the work of the brilliant artist Jiří Grus. He often collaborates on his best work with the scriptwriter (and occasional artist) Vojtěch Mašek, in my opinion perhaps the most inspiring creator of contemporary Czech alternative comics—his recent masterpiece, a brilliant and monumental graphic novel The Sisters Dietl has just appeared in English from Centrala. Some current books by younger creators are also very promising: Karel Osoha, a phenomenal, manga-inspired and quite unique cartoonist is a growing presence in Czech comics, while Kateřina Čupová has reached readers in Italy, Spain, France, Turkey, and South Korea with her original adaptation of Čapek’s R.U.R.

VOJTĚCH MAŠEK – THE SISTERS DIETL ©LIPNIK / CENTRALA

JS: And, last but not least, what are you currently working on?

MJ: I’ve just published a book on the beginnings of Czech detective fiction, called Případ Clifton (The Clifton Case). It’s an in-depth reading of an early twentieth-century scrapbook series that greatly influenced Czech popular culture. It focuses on an original Czech detective named Léon Clifton, who, like Nick Carter, enjoyed great popularity. In addition, Pavel and I are finishing a grant project devoted to Czech (and Slovak) popular literature of the 1920s and ’30s. I also edit books of poetry . . . because literature and culture is either good or bad, and it doesn’t matter whether it’s poetry or comics.

PK: Besides working on a book about interwar popular literature, which Michal has already mentioned, I have a few minor studies on the history of Czech comics in progress and I would like to turn my occasional articles about the Czech life of Felix the Cat into a small monograph. I have also long been interested in Czech-Japanese cultural contacts, especially in the literary field, and I hope to produce some more coherent work on this topic in the next few years. But, to return to the field of comics, I see the comparative history of Central European comics as a long-term challenge, which would require a truly international research team. If we put Czech, Polish, Hungarian, and even (East) German comics of the twentieth century side by side, a number of common tendencies, formal characteristics, and immediate influential links will emerge that cry out for a truly thorough and considered treatment.

Michal Jareš is a literary historian, editor and poet, and staff member of the Institute for Czech Literature at the Czech Academy of Sciences. His research interests range from twentieth- and twenty-first-century Czech and Slovak prose, poetry, and popular literature, through the history of comics to the history of publishing and lexicography. He is is the co-author of books on Czech and Slovak comic art, Czech crime fiction, and the beginnings of Czech pulp fiction, and reviews fiction, poetry, and, occasionally, film for a variety of literary journals. He is also the author of a comic strip, Zlá ovce (Bad Sheep).

Pavel Kořínek is a scholar and historian of comic art. He is the scientific secretary at the Institute for Czech Literature at the Czech Academy of Sciences, and a founding member of the Czech Centre for Comics Studies. He has taught courses on the history and theory of comics at Charles University and the University of Applied Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, as well as Masaryk University in Brno, is a regular reviewer of contemporary comics and translated literature at Czech Radio and the biweekly A2, and since 2018 has served as the Chair of the Czech Comics Academy. He is the author and co-author of several of books on comic art and has curated exhibitions of Czech comics in cities around the Czech Republic and worldwide.

Julia Sherwood was born and grew up in Bratislava, (Czecho)Slovakia. Since 2008 she has been working as a freelance translator of fiction and non-fiction from Slovak, Czech, Polish, German and Russian. She is based in London and is Asymptote’s editor-at-large for Slovakia.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: