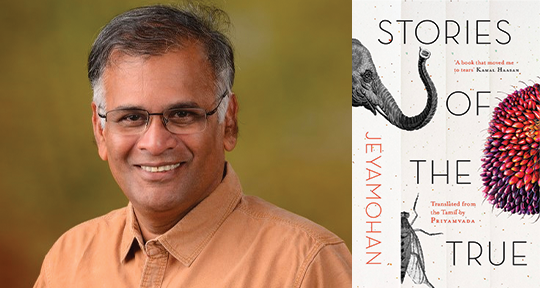

Stories of the True by Jeyamohan, translated from the Tamil by Priyamvada, Juggernaut Books, 2022

Aram—this was the original Tamil title of Jeyamohan’s collection of short stories first published in 2011, recently released in Priyamvada’s English translation as Stories of the True. Priyamvada deems aram a complex word, even going as far as to call it untranslatable. In other contexts, aram has been rendered as “virtue” or “ethics,” and while the former is possibly the closest in meaning, Priyamvada notes that “aram seems . . . a far more capacious word than ethics.” The familiar Sanskrit word “dharm”’ might be a near-perfect equivalent, and it has a Tamil variation as well, but Priyamvada resisted inserting Hindi or Sanskrit words in place of the Tamil, even if they would be relatively well-known and understood by English readers. This is in part her way of dissenting against the infamous political project of promoting Hindi as a national language, autocratically imposed in an attack on linguistic pluralism. Similarly, this choice served to geographically, culturally, and linguistically ground the stories in Southern India. She writes, “It wasn’t just the stubbornness of someone from the south of the peninsula, but I felt it takes away from the ‘place’ of the stories to be using terms from a different part of the country.”

In her search for a fitting translation of Aram, Priyamvada allowed herself to be guided by the stories themselves and to explore all the “dimensions of aram” that these narratives depicted, as well as the range of ethical codes they encompassed. However, it would be simplistic to consider them, in her words, “simple expositions of virtue.” She writes: “Reaching beyond the understanding of ethics as dichromatic, immutable codes of conduct, the narratives delve into deeper and more complex internal dilemmas . . . It is in this quest that the stories move from podhu-aram, a collective dharma, to thannaram or swadharma, the dharma of an individual.” In her estimation, the stories in this collection feature a mix of characters, some of whom have already finished their journey of self-discovery and some who are still on the way. Among the former, they are distinguished by “their steadfast adherence to ‘their truth,’” and for the latter, by “these ‘moments of truth’ [that] also stand illuminated.” In a nutshell: “The stories hold in tension a truth realized, and a truth to be discovered.”

So, Aram becomes Stories of the True. Furthermore, the title’s aptness extends beyond this particular paradigm. The twelve stories collected in Stories of the True are all based on the lives of real people, for whom the English edition provides over-arching, contextual biographies at the end. Some of them are obviously personally known to Jeyamohan; their names have been changed in the story to maintain their privacy and their bios do not figure in the appendix. Seven out of the twelve stories feature explicitly identified figures from the history of Tamil Nadu—politicians, artists, writers, humanitarians, and activists—which underpins the general setting of the collection. The English title is even more perfect since Jeyamohan figures as a character in a few stories himself; he is the first person narrator of “Aram—The Song of Righteousness,” “Peruvali,” “The Churning Curd,” and “One World.” The latter three stories count among the seven that feature actual people, identified by name.

Jeyamohan states: “Arising from the most fundamental questions of aram, every one of these stories celebrates the triumph of humanity.” He also writes in the Preface: “I have no desire to be mired in phony idealism, for it is meaningless to ignore the practicalities and live in a dream. If we approach human history—one that has been created by the ‘will to power’—without being conscious of reality, we will only end up fooling ourselves.” He firmly holds that a historical sense is crucial for literature, and Stories of the True is an examination of how “[his] view of idealism measured against the mighty torrent of history.” Contending that his stories “don’t separate idealism from the lived life,” he asserts: “Through the stories of real people who had lived lives steeped in idealism, through keen eyes that would take stock of them, I felt I could raise the questions I needed to examine.” No matter the forces that amass against idealism—such as weapons raised by pragmatic tradition—it cannot be broken, and always spreads.

The reality of the caste system is one of the major forces that Jeyamohan strives to highlight and dismantle. Its presence in these stories and in the lives of their characters is as matter-of-fact, unremarkable, and ordinary as it is in actuality. It bears noting that all of these stories are set in the twentieth century, with most taking place mid-century. Tamil Nadu, like any other place in India, had its fair share of caste discrimination and societal stratification, made most visible by the fact that people used their caste names as their surnames. Caste could, and still can be identified through surnames in other parts of the country as well. With Periyar and Iyothee Thass before him, as well as the Self-Respect Movement, a lot of Tamilians and other people from South India have stopped using caste-based surnames and have elected to go only by their given names instead, if fashioning surnames out of the initial of their fathers’ or husbands’ given names or their native place is required—just look at Jeyamohan and Priyamvada.

Caste therefore figures in a lot of stories, usually in passing with remarks about purity and pollution, lowly ancestral jobs, and social mobility, though it is at the centre of two stories. In “He Who Will Not Bow,” A. Nesamony, real-life lawyer and political leader belonging to the ‘low-caste’ Nadar community, is featured as a character. The biographical context at the back mentions the discriminations he faced in court and the decisive actions he took to eradicate those systems. “He Who Will Not Bow” details the life of Karuthaan Nadar, told by his son Vanangaan as he explains the reason for his unusual name, which translates to the title of the story. Karuthaan worked on the plantation of an ‘upper-caste’ man along with his father and ran away to the city when he was just eight. He worked sundry jobs to make ends meet. One of those was at a tea stall where Nesamony was a frequent customer. The lawyer’s refusal to bow to caste oppression led Karuthaan to follow the same path as he painstakingly educated himself, got a job, and defended his dignity and worth.

“A Hundred Armchairs,” the second story focusing on the caste system and by far the best story of the collection—truly an impressive piece of short fiction—does not have an identified real-life figure. The narrator of “A Hundred Armchairs” is an IAS officer from the Nayadi community, a Scheduled Tribe under the Indian Constitution. As a boy, he lived on the streets with his mother, all of his siblings dead, begging and scavenging for food. He is taken in by an ashram. He is kept away from his mother but is also fed, clothed, and educated. Even in the civil service, he feels powerless, undermined due to his caste to the point where he bitterly shuts up a ‘low-caste’ doctor lamenting his mistreatment by saying, “I’m my department’s scavenger [too].” When he is reunited with his mother, she has mostly lost her mind. Half of the time she is scared of his attire and mannerisms, and the other half she begs him to strip, to get off the thamraa’s chair—the lord’s chair—and run away with her.

It’s a disturbing, heart-breaking story that lays bare the cruel functioning of caste in our society and the destabilization it causes in people’s lives, even when they have conquered the arbitrary demands of modernity. This story is not the only one that highlights religious benevolence. In “The Palm-Leaf Cross,” the first person narrator belongs to a destitute family engaged in the business of palm jaggery. When his father dies in an accident, the sahib at the big missionary-run hospital—none other than Dr. Howard Somervell—tells them to convert and make their life easier. In both stories, the altruism of religion is undermined by the prerequisite to adhere to its tenets. Most of his family chooses to convert to Christianity, and when the narrator asks his mother if it was merely for the food, she vehemently agrees: “Yes, it was only for food. Christ is nothing more than rice and meat to me.” This story demonstrates why Christian missionaries were so successful in Southern India. The downtrodden just wanted succour; salvation was secondary.

Caste isn’t the only great divider in these stories; it’s class, too. In fact, most of these stories depict people located at the intersection of both. In “He Who Will Not Bow,” Vanangaan relates what his grandmother used to say: “[H]unger is like a house on fire. Throw all you’ve got at it, in order to douse it. You needn’t stop to think if it’s good or bad. There really is nothing more cruel than hunger.” It is this exact hunger that forces the narrator in “A Hundred Armchairs” to join the ashram, that makes the narrator’s mother in “The Palm-Leaf Cross” convert to Christianity. It is this hunger that wills the narrator of “The Meal Tally” to cry when he is fed with lovingly gruff generosity by Kethel Sahib at his eatery, where you pay what you wish or don’t pay at all. Hunger plays a role in the desperation of the old man in “Aram—The Song of Righteousness” as he begs for payment due. The convergence of caste and class demonstrates the compounding forces in the lives of these characters, showing the variance in their lived experiences as well as their similarities.

Many stories are marked by extended discussions on philosophy and spirituality between real-life figures and other characters, an exchange of ideas that signifies just how close fact sits to fiction. In “Elephant Doctor,” Dr. V. Krishnamurthy—a pre-eminent conservationist, wildlife vet, and elephant expert—reiterates how the machinations of power have no standing in the forest, which unravels all conceit. “Peruvali” revolves around a dying Komal Swaminathan—a Tamil writer, film director and journalist—with Jeyamohan as the first-person narrator. They discuss faith, pilgrimage, transformative religious experiences, the meaning of life, and the worth of humanity. In “The Churning Curd,” Professor C. Jesudesan—a college professor, literary historian and notable critic—opines on the Kamba Ramayanam, Kamban’s twelfth-century Tamil epic based on Valmiki’s Ramayana, to expound upon the absurdity of existence and the nature of suffering. “One World” is about a chance meeting of Jeyamohan with Garry Davis in Ooty. Davis, an international peace activist, advocated for “One World, One Nation,” the eradication of borders and passports, and pushed for humanity to come together as one.

Priyamvada has written about the challenges she faced during translation in her note: “Jeyamohan is a culturally rooted writer . . . Dialect is an integral part of the stories in Aram, no doubt; the change of caste and place, for instance, is instantly understood in the original through a change of dialect. So there is bound to be some loss in translation. However, I feel the drama and the essence of the stories are strong enough to withstand [it].” She emphasizes that it is more vital to focus on what is gained through translation. True to her desire to evoke “place” in these stories, her decision to use Tamil words—without italics—instead of equivalents or substitutes is laudable. Moreover, she does not awkwardly provide their meanings within the text, and there are no footnotes nor a glossary. It’s hard to believe that this is her first full-length translation, and it comes as no surprise that her translation of Vellai Yaanai by Jeyamohan, White Elephant, has been chosen for a 2023 PEN/Heim translation grant.

Areeb Ahmad is Editor-at-Large for India at Asymptote and Books Editor at Inklette Magazine. Most of Areeb’s writing can be found in his bookstagram, a true labour of love. His reviews and essays have appeared in Scroll.in, Gaysi, The Chakkar, Mountain Ink, and elsewhere.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: