In the first of two interviews on the thriving Czech comic art scene for the Asymptote blog, we introduce Lucie Lomová, artist, writer, and author of numerous comic books for both children and adults. Comic art and graphic novels are increasingly gaining recognition as a serious art and literary form; since the start of the millenium, the Czech Republic has seen a boom in the genre. In the second interview, two Czech literature scholars will paint a more comprehensive picture of the scene for Asymptote readers. Dubbed “the queen of the Czech comic,” Lomová is the best-known woman comic book author of the new, postcommunist generation, with three coveted Muriel Awards, including two—for original script and best original Czech comic—for her graphic novel, Divoši (Savages) to be published in English translation by Asymptote’s Editor-at-Large for Slovakia, Julia Sherwood, and Peter Sherwood. We are delighted to introduce Lucie Lomová to Asymptote’s readers through this interview, conducted by Julia over email.

JS: You are a graduate of the Theatre faculty at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (DAMU), but you switched to writing and drawing comics in the early 1990s. In those days, this kind of career change required quite a lot of courage—you said in an interview: “To choose comics as one’s profession was rather like trying to make a living by catching earthworms.” What motivated you to take the risk?

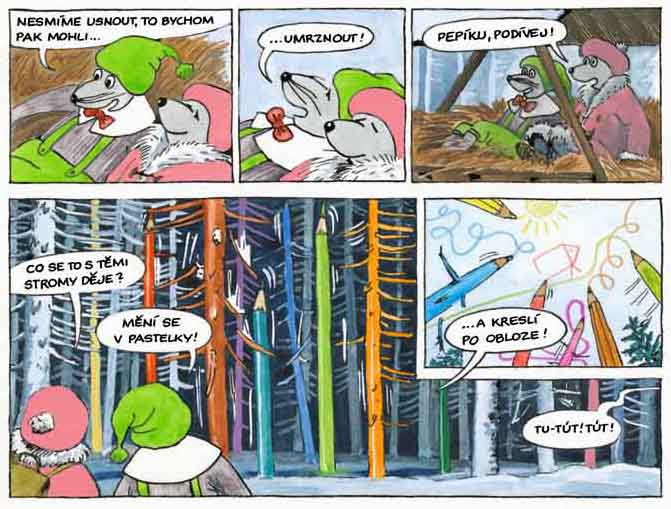

LL: Did I really say that? Perhaps I wouldn’t use that comparison now, but it‘s true that in those days comic art was a totally marginal and underrated genre, with publication opportunities few and far between. But, it didn’t really require any special courage on my part. The year of the Velvet Revolution, 1989—a turning point in every respect for everyone—saw the publication of my first comic strip about Anča and Pepík, a couple of mice kids. My sister Ivana and I had worked on it together for three years, writing the story and doing the drawings. I had just graduated in dramaturgy and started working in a theatre in Šumperk, a small town about 200 kilometres east of Prague. When the Velvet Revolution came, I decided to return to Prague, although I didn’t really have a clear idea about what I was going to do. I wrote art reviews for newspapers, drew cartoons, and pondered what I should apply myself to in all this new freedom—just then, the children’s comic journal Čtyřlístek (The Four-Leaved Clover) invited me to write and draw more stories about Anča and Pepík for them, this time on my own, as my sister had moved on to other things. In the summer of 1990, I hitchhiked to Greece with my boyfriend. We were penniless, but overjoyed and excited about all the possibilities that had opened up before us. I remember that it was during the long rides in strangers’ cars that the ideas for the first three stories came to me, and once I was back home, I got drawing. For the following ten years, drawing comics for Čtyřlístek was my bread and butter.

JS: How much did you know about the international comic art scene when you were starting out, and what were your models and sources of inspiration, both then and now? Who are your favourite comic artists, domestic and international?

LL: I knew almost nothing about the scene. Of course, my main home-grown inspiration was Rychlé šípy (The Rapid Arrows) by Jaroslav Foglar, the most important comic art series for generations of Czech children; the 1930s and ‘40s stories of Punťa the Puppy, which I inherited from my mother; I also loved Ferda Mravenec (Ferdi the Ant) by Ondřej Sekora, as well as cartoons by Josef Lada, Josef Kalousek… But my defining experience was the year I spent in Chicago with my family, where my father, a parasitologist, was a visiting professor at the University of Illinois. It was 1969, I was five years old, and I fell in love with America with all its pop culture—and that of course included children’s comics.

I always find it hard to answer questions about my models and inspirations—I absorb everything I come across without making use of it in a conscious way. When I was growing up, “aping” others was frowned upon as something shameful, but in fact, everything we ever ever learn, we learn by imitating someone—when I look at some of my childhood drawings, I can easily tell what was being shown on TV at the time or what book I was reading. Nevertheless, all these books, pictures, films, and experiences create a storehouse, a repository—the compost that we later use for growing our little plants.

There are many, many authors I admire, both here in the Czech Republic and abroad. At the beginning of this millennium, I was enraptured by the discovery of French comics, authors such as David B., Nicolas de Crécy, Joann Sfar, Pascal Rabaté, Blutch, and many others. Then there’s American and Canadian alternative comic art, obviously Art Spiegelmann and his Maus, which was quite quickly translated into Czech; Seth, Charles Burns, Daniel Clowes, and, above all, the comic art genius Chris Ware. There are also German, Belgian, British, Austrian, Norwegian and Italian comics… The Czech authors I would particularly recommend include Václav Šlajch, Jiří Grus, Vojtěch Mašek, Lela Geislerová, Marek Pokorný, Karel Osoha… I could go on and on, but I’d better stop there.

JS: Your breakthrough series Anča and Pepík continued to appear in the journal Čtyřlístek throughout the 1990s, and was then published as a book and adapted into an animated film. Looking back, how do you see this period? What changes have you observed since then in the children’s comic market in terms of form and style, as well as readers’ expectations?

LL: I have fond memories of my Anča and Pepík years. It was a relatively idyllic and productive period, and I was able to juggle writing and drawing with looking after my young children. Sometimes I did both things at the same time: had my children sitting in my lap and watching me draw. Believe it or not, back then I wasn’t really interested in comic art theory or in following international trends, or that sort of thing. The editors at Čtyřlístek gave me the freedom to work at my own pace; I wasn’t expected to hand in a specific number of episodes by strict deadlines—it was entirely up to me how much I would do. I did all the drawing and colouring by hand; the only technical device I used was a makeshift contraption: a desk lamp I placed on a kneeling chair and used to shine a light on my sketches from below through a sheet of glass taken from a bookcase. I guess almost everyone makes use of digital technology nowadays. Storytelling in comic books has also developed by leaps and bounds. Comic art started in newspapers and magazines where space was limited, which made it quite confined, a great deal of story having to fit into a small space. The large comic albums that are being published today have enough room for large panels and so on for varying the pace of the story. Lately, manga has been a big influence, especially for younger authors. There are many comic art magazines, including the legendary Čtyřlístek that is still going strong, although it now features different authors, of course. Even though I no longer follow the children’s comic scene in detail, I believe that children still expect the same thing: interesting stories, relatable characters, attractive pictures, fun, and adventure.

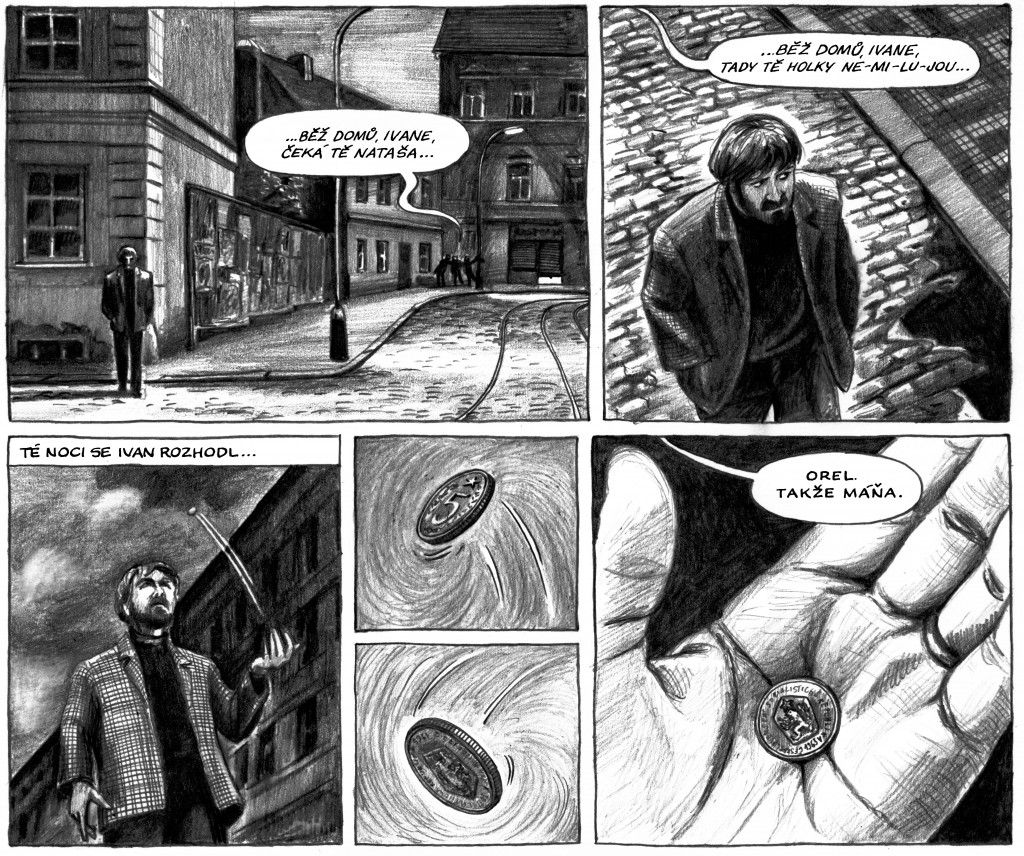

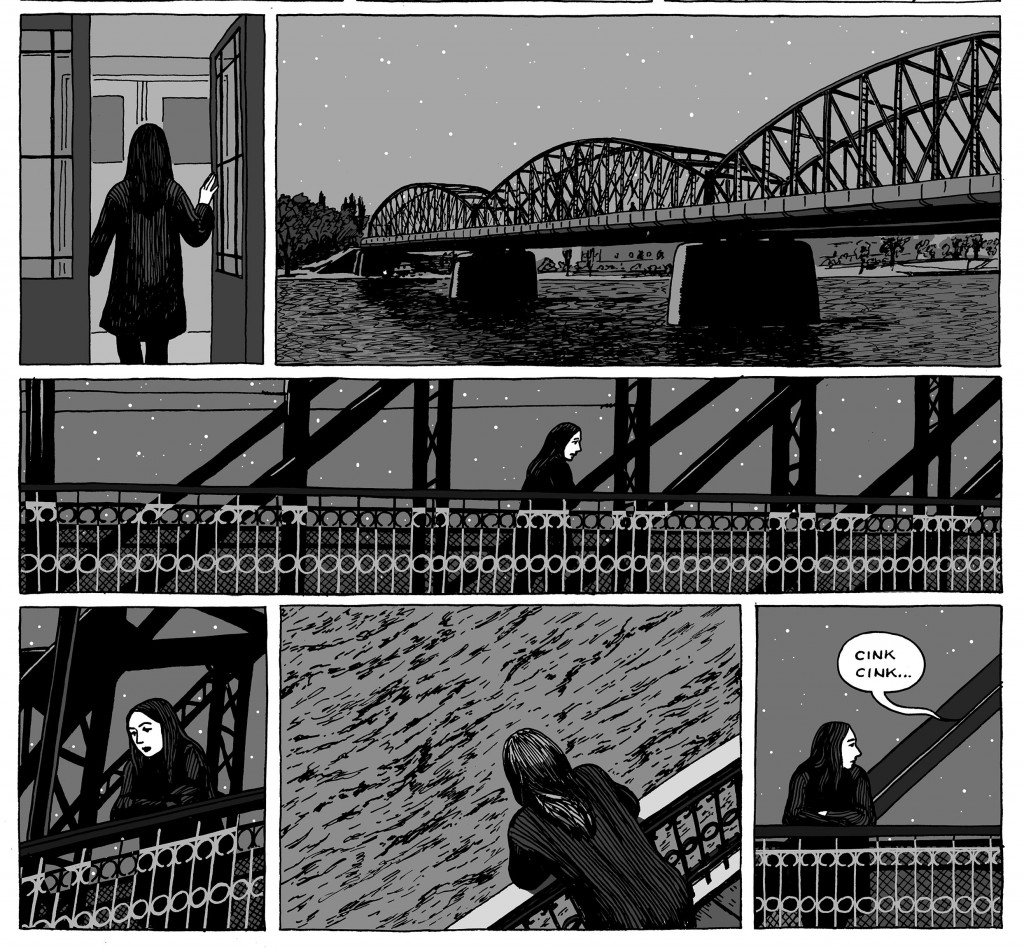

JS: Your first graphic novel for adult readers, Anna en cavale, was published in 2006—though not at home, but in France, with the Czech edition (Anna chce skočit) following a year later. How did that come about?

LL: After ten years of drawing stories about the mice Anča and Pepík, I reached a point when I needed a change of direction. Perhaps quite a radical one. I was increasingly drawn to astrology, practised tai-chi, and even mandalas for a while, painted on glass—I thought it through to the last detail, right up to short texts accompanying individual mandalas; I had them encased in glass and had holes drilled through them, and I actually sold quite a few. Tai-chi, mandalas, astrology—all this was linked to my search for a focus and for a way of stirring up lethargic energy. Well, my life ended up quite stirred up indeed.

Then, it struck me that I could try my hand at a comic book for adults. I should mention that this was at a time when there were really no comic books for adults in my country, with the possible exception of Maus. After thinking about it for a while, I slowly started drawing and collecting ideas, and just at that point my uncle told me that, browsing on the internet, he had come across a visual artist who was my namesake, apart from the Slavonic feminine ending -ová: Lucie Lom. When I looked into the matter, it turned out that this was not a woman but a company run by two (originally three) French graphic and stage designers. I took this as a clear signal that something pivotal was about to happen, and I wrote to them explaining that I was the real Lucie Lomová, that I had studied theatre and was a comic book author. Then, I went to see them in Angers, and it felt like meeting close friends. Some time later, they were curating a new exhibition for the Comics Museum in Angoulême, whose director at the time was Thierry Groensteen, a renowned theorist of comics. Thierry had just founded a publishing house, Editions de l´An 2, which included a series called “traits féminins;” he happened to be on the lookout for women authors, preferably from outside France. The two men at Lucie Lom told him that I’d been publishing comic books for children for years and was now working on one for adults. Before long, Thierry wrote to me asking to see a synopsis and a few sample pages. So this is how I ended up publishing my first album, Anna en cavale (Anna Wants to Jump) in France—it was handed to me on a silver platter, so to speak.

Quite early on, I told my publisher that this was going to be a realist-mystical-psychological-humorous-adventure story, and it has indeed turned out to be a genre-defying graphic novel. It starts out depicting Anna in her boring everyday routine and a relationship that is withering away, but her life begins to change from one day to the next, turning into a frenzied quasi-road movie full of unlikely twists and turns, humorous situations, family flashbacks, and dream sequences, in which the action element, the chase, doesn’t actually play a very important role. Rather, the story demonstrates the latent possibility of change, the chance that somewhere beneath our humdrum everyday life there lurks a lively bubbly stream that can surprise us at any moment, turning our life upside-down and carrying us away to lands unknown.

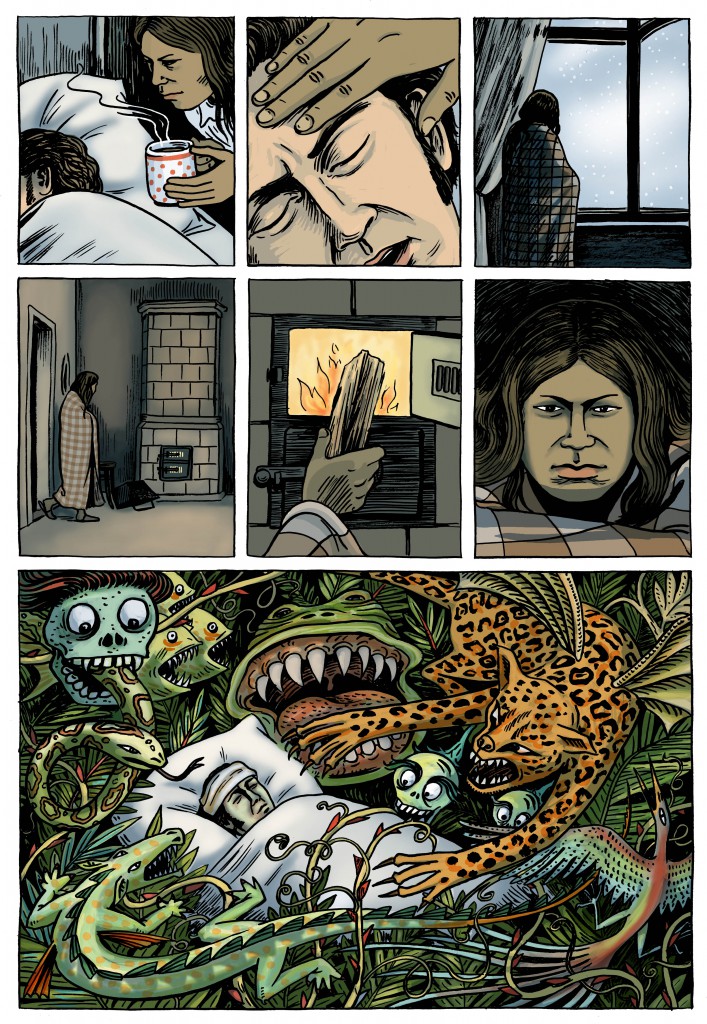

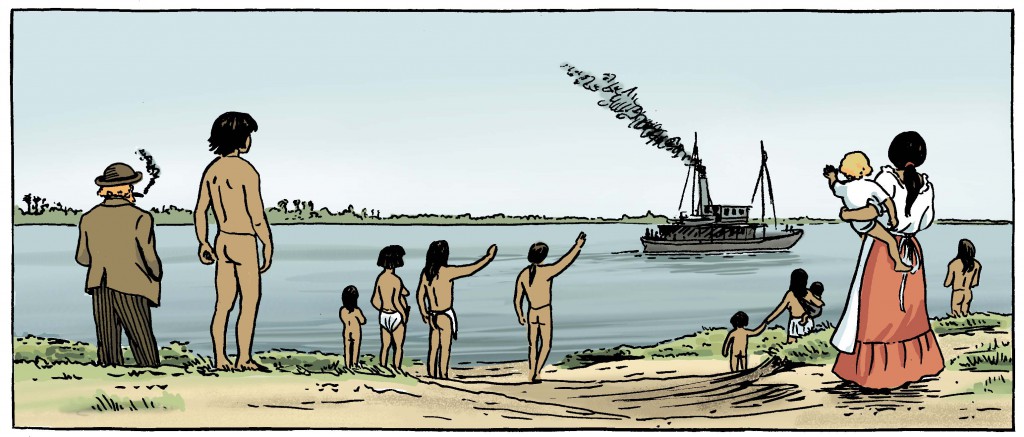

JS: Your next graphic novel, Divoši (Savages), was published in 2011, simultaneously in French and Czech. It tells the real-life story of Alberto Vojtěch Frič, an early twentieth-century Czech traveller and cactus collector, who in 1908 returned to Prague from a trip to what is now Paraguay, bringing with him Cherwuish, a Native American. How did you discover this remarkable story and which aspects of it caught your interest?

LL: I came across Cherwuish in a pub or, to be precise, a wine bar, while chatting to a few girlfriends of mine. One of them was raving about a book she’d just read: the notebooks of Alberto Vojtěch Frič. So, I read it too and was bowled over. I fell in love with both protagonists: young Frič, the intrepid individualist who always followed his convictions, never mind what others thought, as well as Cherwuish, the son of a tribal leader of the indigenous Chamacoco people, bravely setting out into the unknown. Frič did not bring him to Europe as a fairground attraction, a horrible fate not uncommon for tribespeople seen as “exotic” in those days. Rather, trying to find treatment for a mysterious sickness that afflicted the Chamacoco, Cherwuish first travelled with Frič to Asunción, then to Buenos Aires, hoping that once he recovered, he would also be able to help his people get better. The two men ended up in Prague, where Cherwuish finally found help. He lived with Frič for a whole year, while his host gave lectures to raise awareness of the situation of Native Americans and earn enough money for his return voyage. My book is really the tale of a classic journey there and back, with many adventures from which the hero emerges transformed, at a time when our civilisation was brutally and unceremoniously colonising territories still inhabited by dozens of indigeneous tribes, subjugating and killing them and labelling them savages. However, the title of my book, Savages, raises the question of who in fact are the savages. To what extent are we shaped by the society we live in? How far are we willing to swim against the current? What do we all have in common and is communication at all possible? Can two different cultures enrich one another without one of them being destroyed in the process?

JS: Colonialism brought untold suffering and destroyed many native civilizations, as is now increasingly recognized around the world. However, as far as I am aware, the dreadful legacy of colonialism is rarely discussed in your country—could you tell our readers why you think this is the case?

It’s to do with our historical and geographical context. The last time the Czech Lands had access to the sea was, for a brief period, as the Kingdom of Bohemia, two hundred years before Columbus. Being a landlocked country, we never had, and indeed never could have had, any colonies. In addition, our country is surrounded by mountains, which protect us but also isolate us: we tend to focus on our own problems, and that makes us less aware of how we are interconnected with the whole wide world. In the past we have been cast in the role of a more or less oppressed nation, first in Austria-Hungary and again later, following a brief democratic period between the two world wars, under Hitler. After the war, Czechoslovakia came under Soviet domination, the borders were closed, and our society was shielded from outside influences until 1989.

Nevertheless, we can’t claim that colonisation has absolutely nothing to do with us and that we can wash our hands of it: we are a part of Europe and as such we too played an indirect part in the crimes of the past. Also, we had a very patronizing view of the colonized nations and although, fortunately, this has now changed and most people are aware of the burden of responsibility we carry as part of European civilization, one could, from the present-day perspective, unjustly accuse Frič of being patronising or even racist. I, however, think that he was a pioneer of anticolonialism—after all, the Chamacoco regarded him as their friend, they loved and trusted him, and his attitude was in stark contrast to the way other travellers and white people in general treated indigenous populations at the time. I think it would be conceited and arrogant to think that we are “better” than our ancestors. We are just in a different place, having learned from bitter experience.

JS: You are regarded as the “queen of the Czech comic” and are among the few female comic book authors who are responsible for both the text and the drawings in their work. How do you see the position of women in the industry: do they enjoy the same opportunities as men?

LL: Quite a few new women comic book authors have emerged in the Czech scene in recent years. This is partly because the art of the comic has become quite popular and can now be studied at art colleges in this country—for some reason, these courses tend to attract more women than men. Comic art can be studied as a subject in its own right at the Sutnar Department of Design and Art in Plzeň, as well as at a few other colleges as part of courses in illustration or animation. There are some women authors who do both their own writing and drawing, while others team up with a script writer. This kind of teamwork is encouraged at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, whose Department of Illustration cooperates with film and TV scriptwriting students at the Academy of Performing Arts.

However, how many of these promising young female comic artists will stick with comics is quite a different matter, since this is an extremely time-consuming and demanding career that is rarely properly remunerated. It requires a lot of patience and stamina. In addition, the Czech market is quite small compared with many abroad. In terms of equal opportunities, I’d say that it is equally difficult for both women and men to make it in the industry. I am not aware of a single case of men receiving preferential treatment.

JS: In addition to comics, you also illustrate books for children and adults. The first volume of Anča and Pepík has just come out in French (Anča et Pepík)—do you have any plans to return to children’s comics at all? What project are you working on at the moment?

LL: I’m not really into making plans for the future, but at the moment I don’t feel inclined to return to children’s comic books. I’m currently working on a long graphic novel. It will be strongly autobiographical and tell the story of the year I spent in the US. I’ve been working on it for quite some time and expect it to keep me busy for a while longer.

I do have a new book coming out this autumn, though. Its title is Every Day Is New, and it’s a diary of 2017 in comic book form. It’s quite different from anything I’ve done before. After years, indeed decades, of stories I planned and thought through in advance down to the smallest detail, I wanted to enjoy the freedom of improvising and drawing spontaneously. I set myself a few ground rules, including: no preliminary sketches and no thought of potential publication. Five years after I completed it, I took a more detached look and felt that it worked and that other people might also enjoy this subjective kaleidoscope of little everyday scenes. It will be interesting to see how it is received.

JS: Thank you for talking to me and I greatly look forward to Every Day Is New. Good luck with your future projects!

Lucie Lomová is an award-winning Czech comic-book author, graphic artist, and prolific illustrator, whose books have been translated into German, French, and Polish. Her latest graphic novel, Každý den je nový (Every Day Is New) will be launched in Prague on 22 November 2022 and the English translation of Savages is due out from Centrala Publishing in February 2023.

Julia Sherwood was born and grew up in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia. Since 2008 she has been working as a freelance translator of fiction and non-fiction from Slovak, Czech, Polish, German, and Russian. She is based in London and is Asymptote’s editor-at-large for Slovakia.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog:

- A Czech Dreambook: Gerald Turner on Translating Ludvík Vaculík

- Graphic Novel in Translation: Karim Zaimović’s “The Invisible Man from Sarajevo,” Part V

- A Dispatch from European Literature Days 2016: On Colonialism and Literature