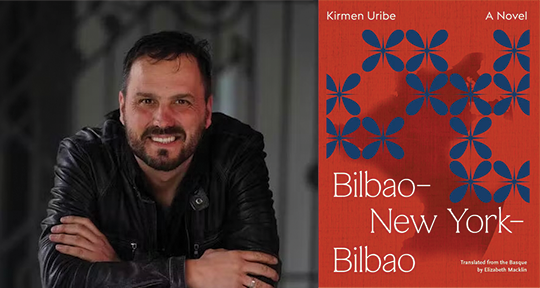

Bilbao—New York—Bilbao by Kirmen Uribe, translated from the Basque by Elizabeth Macklin, Coffee House Press, 2022

“I realized that our dad’s whole family history was made up of round trips, flights, and returnings,” reflects author Kirmen Uribe. Bilbao–New York–Bilbao, a novel which won Uribe the 2009 National Prize for Literature in Spain, stems from the family history in question. Translated from the Basque by Elizabeth Macklin, it is a sort of metanovel that straddles fact and fiction, laying its mechanisms bare. Within the brackets of his own travel—a flight from Bilbao to New York—the narrator’s mind rambles through various elements he would like to weave into his hypothetical novel: interviews, folklore, philosophical reflections, images, and anecdotes. He meditates on structure and process, always on the precipice of making decisions, giving the whole novel the impression that it’s just about to start.

Uribe is from the Basque fishing town of Ondarroa, where the men have historically spent large parts of the year on the water. Urbanization, industrialization, and the mechanization of the fishing industry have by now, however, made the traditional way of life nearly obsolete. As a member of the intermediary generation, the rhythm of this extended round-trip journey is still familiar to Uribe; movement is not a means to an end, but a comfortable and creative mode of being that always ends in a provisional homecoming.

Throughout, the reader senses that his search for the novel’s structure is a search for meaning. Uribe’s desire for the moments that make up his personal, family, and national history to coalesce into narrative is tangible, though he struggles to make them conform. Details, encounters, images—he feels their weight and wants a story to give them coherence. But they resist, and his resulting frustration is echoed by the reader. When a new anecdote begins, we wonder: where does this fit in? Why should I immerse myself in this moment? Is this character major or minor?

Memory has always been the terrain that grounds seemingly disparate moments, and Uribe’s memory is like the ocean maps that his ancestors drew for their fishing journeys; the features depicted are those most salient to the cartographer. Before the time of GPS, Uribe recalls his father drafting a map of his habitual fishing ground off the coast of an uninhabited Scottish island called Rockall. It was a personal map, jealously guarded, that showed the significant underwater features and the migratory patterns of the fish. Rockall echoes through the novel, looming large like a landmark, as it would have been for Uribe in his youth—the place where his father was when he wasn’t home. I looked it up on Google Maps, but as I zoomed out to see where it was in relation to the United Kingdom, it quickly disappeared.

Memory can also be organized like a museum, and one of the central anecdotes of the novel takes place in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum. On the day of his cancer diagnosis, Uribe’s paternal grandfather takes his mother there to see a particular painting by Aurelio Arteta. Arteta allegedly marginalized himself to regional importance when he passed up the 1937 commission for a painting to represent Spain’s republican government at the Paris World’s Fair—a commission that then went to Pablo Picasso and became the famous Guernica. Arteta is a recurring character throughout the novel because of his tenuous connection to Uribe’s family; a museum is a meticulously curated space, yet visitors, like Uribe’s grandfather, tend to navigate by the heart.

Or perhaps memory is like a dictionary. Uribe is hyperaware that when a language is endangered—like Basque is—there are certain words that die first. The lexicon of coastal tradition falls into this category. In resolving a dispute about the Basque word for a particular seabird, Uribe consults the Biscyan Fishermen’s Lexicon, a formal dictionary which contrasts with informal ones. In the bank where Uribe’s wife works, “A retired fisherman regularly gives her words, sayings, the names of fish. He deposits antique words safe in the same place they keep the money in.” Meanwhile, Uribe himself tracks down another informal dictionary of lost hand signals.

Maritxu recalls very well the last time she saw her father. From a distance he was looking out for his little girl. He signaled with his hands, laying one on top of the other in a stroking caress. Maritxu made the same gesture to me, two hands caressing. It means “Love you, love you,” my aunt explained in her diction of eighty years ago.

I hadn’t known of that hand sign, it must have been a signal lost long before.

But no matter what object one compares memory to, it is a capriciously structured thing, and the structure of the novel mirrors this. Its method and intention are subject to emotion and chance.

The transmission of memory—cultural, regional, and personal—relies on storytelling, and as such, Uribe’s storytelling often takes on the flavour of myth. “Our Aunt Margarita,” he relates, “used to tell us when we were little that Dad had once lost his wedding ring in the ocean and that she herself had found it in the belly of a hake.” The improbability of the story so entrances him that he writes a poem about it as an adult, prompting a deluge of letters from readers telling variations of the same story. Some are personal, but others trace the roots of the story back to Herodotus. A dash of the supernatural and the creation of a participatory discourse transform a story into a myth. The mythologization of one’s personal repertoire begs the question of significance: what makes something worth telling? Are our myths different from the myths? How does the role of protagonist differ from that of bard?

Translation is a constant companion to the act of storytelling—especially for a marginalized language like Basque. An English speaker once remarked to Uribe on the visual strangeness of Basque, a language that makes liberal use of the letter x, “Your language looks like a treasure map . . . if you just forget all the rest of the letters and focus on the letter x, it looks as if you could find out where the treasure is.” When Uribe lands in New York, he will give a talk about a gathering of writers from various European languages, which he attended in Estonia. During that encounter, he found catharsis and affinity in the exchange between minority literatures, particularly with Gaelic. The speakers of both Basque and Gaelic, he discovers, believe their language to be that of Tubal at the Tower of Babel. Gaelic, furthermore, is the language indigenous to the region where his father spent so much time fishing. Bringing this experience—and indeed this book—into English isn’t presented as a concession to the world’s colonialist languages: “Our literary tradition . . . small, poor, disorderly. But the worst thing is its being secret . . . the best way to air out a house is to open up the windows.”

If the act of translation bridges speakers of disparate languages, something else is needed to resolve ruptures between speakers of the same language. In Basque Country, as in the rest of Spain, the Spanish Civil War created fissures within communities and families. Uribe recalls how neighbors turned each other in to the authorities, friends turned on each other, and society refused to allow anyone neutrality. Though Franco’s rule ended decades ago, Uribe still feels the fallout of that divided time. His own beloved paternal grandfather had supported Franco’s fascist regime.

That man who when he had a scant few months to live took our mum to the museum, that man who used to gather the kids around him and tell them stories, the allegedly good and openhanded man, was in Larrinaga jail, apparently, for having come down on the side of the fascist uprising. At first I found that hard to take. I couldn’t comprehend it.

It’s his maternal aunt whose simple words help him cope with the contradiction: “Yes, I know it’s startling to have people from both sides in your home in wartime. But ideas are one thing and the heart is another.”

A boat that’s steady in the water catches the most fish. She has to squat down in the water, sturdy. That’s why your ballast is important. The more weight, the more fish. If her prow is higher than her stern, or vice versa, there’s no fishing. People are like that too. A person’s got to be steady on his pins. And so does a boat. Otherwise there’s no catching fish.

Upon hearing these reflections from a fishing boat captain, Uribe immediately draws a parallel to his own writing process. Movement isn’t fruitful in itself. It’s instead the interior gravity that gives a vessel orientation and strength to thrive, to eventually return home, overflowing with bounty.

Lindsay Semel is an assistant managing editor at Asymptote. She daylights as a farmer in North-Western Galicia and moonlights as a freelance writer and editor.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: